After a full year of hoopla and hype the National Park

Service celebrates its official centennial

with a big bash at Yellowstone Park, the original gem in a system that now includes 125

National Parks and Historic Sites, 79 National Monuments, 29 National

Memorials, 25 National Battlefields and

Military Parks, plus scores of Nature Preserves and Reserves, Recreational Areas, Scenic Rivers, Sea Shores, Lakesides, Trails,

Parkways, and Special Designations like

the White House and National Mall. There are now Park Service facilities in every state and within an

hour’s travel of 90% of the population.

But National Parks are 50 years

older than the Park Service but were haphazardly

managed on sort of an ad hoc basis by the under-staffed

and funded Department of the Interior and

the U. S. Army. Yes, troops

were the first Park Rangers

after early tourists were surprised if unmolested by the Nez Piercé

on their epic attempt to escape

the Army to Canada. In the Yellowstone, many of them were Black Buffalo Soldiers.

An early glimmering of the idea of preserving

scenic wonders came in the midst of

the Civil War when in order to reward California’s loyalty to the Union—it had been a close thing—Abraham Lincoln signed into

law an Act supported by Sen. John Conness and leading citizens transferring the Yosemite

Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove to

the state to “be held for public use, resort, and recreation...inalienable for

all time.”

The first actual National Park was

not created until 1872 when Ulysses S.

Grant signed into law the Act creating Yellowstone National Park. The large, remote area in northern Wyoming, southern Montana, and a sliver of eastern Idaho had attracted national attention when the reports of the private

Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition of

1869 and the larger semi-official Washburn-Langford-Doane

Expedition in 1870 detailed the wonders

of its geysers, thermal springs, and the magnificent Falls at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

Writer and lawyer Cornelius

Hedges, a member of the latter expedition, publicly advocated for

preservation of the region and had the backing of some Territorial

officials.

But it was not until railroad tycoon Jay Cooke, not normally

associated with selfless public advocacy,

threw his considerable weight around

in Congress that action was

taken. Cooke was interested because he

saw that he could promote access to the Park from his Northern Pacific Railway to supply passenger traffic on his railroad which

was still under construction. Indeed for

years after Cooke lost control of the road, the Northern Pacific flooded the East with enticing brochures and colorful posters that made the park a

popular attraction to a growing middle

class with disposable income and

leisure time.

|

| Buffalo Soldiers on patrol in Yellowstone Park in the 1880's. |

Yellowstone was meant to be a singular creation. But once a precedent was set other local interests were able to access the

proper powerful forces in Congress

press for the creation of Parks in their area.

Michigan officials and Great Lakes shipping promoters got Mackinac Island in northern Lake Huron protected when the garrison

at Ft. Mackinac was in danger of

being removed since another war with

the British in Canada had become remote.

The Island was already a resort destination. It was approved as a National Park in 1875

and its Army garrison was made its guardian.

The private resort on the Island flourished while the Federal Government

assumed the expense of upkeep on the Park and preservations of the Fort and

scenic wonders. The park flourished for

twenty years before operators of the resort began to resent Federal regulations

and lobbied successfully to have the Park and fort turned over to the state of

Michigan.

In 1890 Sequoia National Park was created in California and the following

year Army Cavalry units took over

the care of Yosemite Park, still officially owned by the state. In 1906 the Federal government assumed

ownership and control of the Park.

The system that was hardly a system bumped along. Not

much money was spent. Improvements were often limited to dirt roads, crude trails, and the most basic of campgrounds and picnic areas. Anything

more elaborate was left to concessionaires who operated rustic inns or elegant resort hotels. But

attendance and public interest grew year by year. The Sierra

Club and other early conservation

groups lobbied for improvements and expansions.

Things really took off when enthusiastic outdoorsman and conservationist Theodore Roosevelt fell

into the presidency thanks to an assassin’s bullet in 1901. Not only did he create the United States Forest Service and National Forest system, scores of Bird Sanctuaries and Game Reserves, but he added new

National Parks including Crater Lake,

Mesa Verdi, and Windcave in South Dakota.

Residents of the South West had been advocating

preservation of the ruins of several

cliff dwellings and Pueblos which were threatened by looting pottery hunters and vandals.

Another railroad, this time the Santa

Fe, lent its support. These sites

were considered worthy of protection and preservation, but the desolate surrounding mountains and deserts were not and gold, silver, and copper mining companies coveted the land for exploitation. That left isolated pockets that were considered too small to be designated a

traditional National Park and there was no precedent

for preserving archeological and historic man made sites. With

Roosevelt’s support Congress passed the Antiquities

Act of 1906 to give the President the authority to create National Monuments from public lands, by presidential proclamation, to protect significant natural, cultural,

or scientific features.

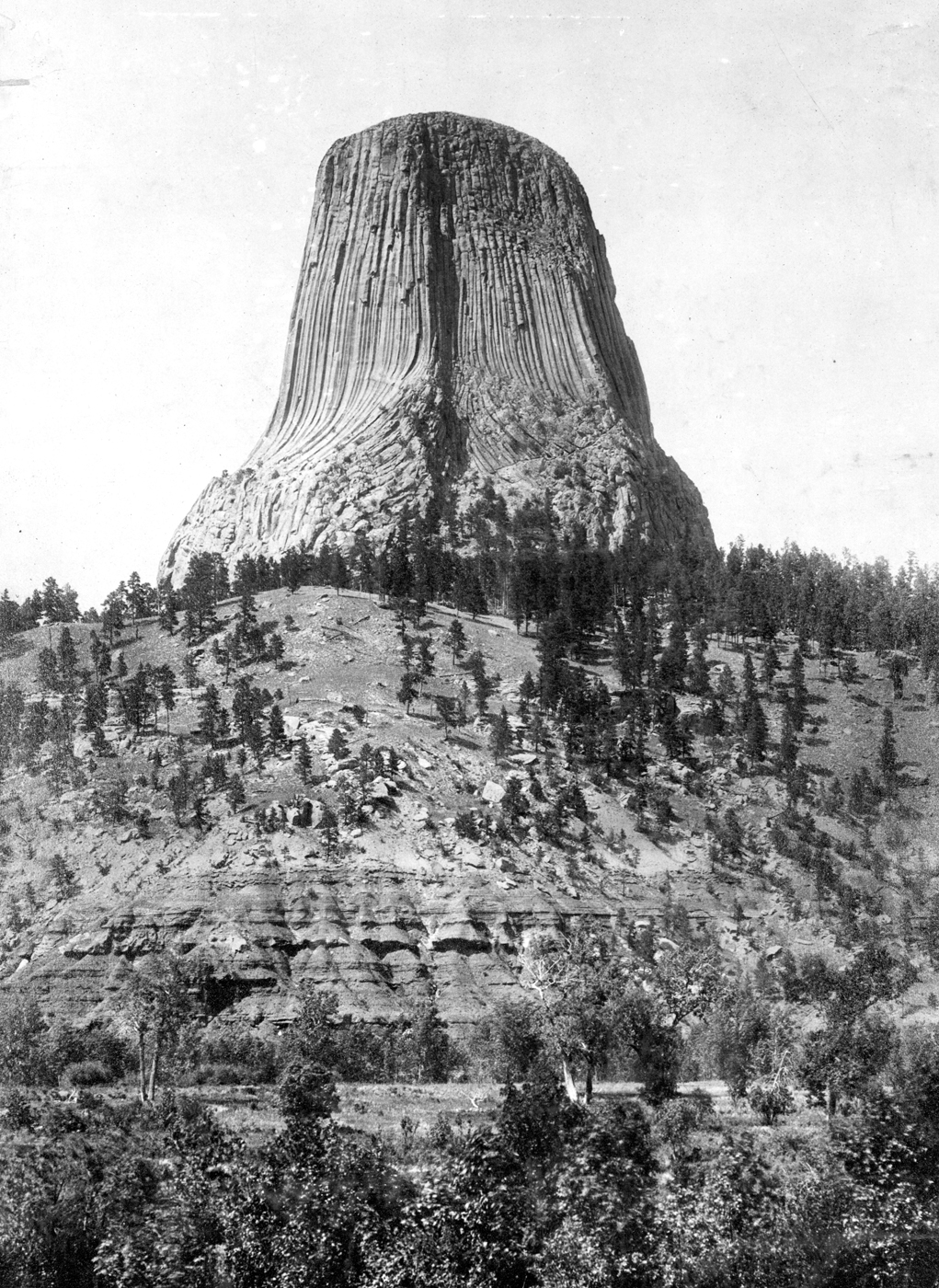

|

| Devil's Tower in 1900, soon to be made the first National Monument by Theodore Roosevelt. |

The first National Monument created

was Devil’s Tower in northeast

Wyoming in the area of Roosevelt’s old stomping

grounds as a South Dakota rancher

in the area around the Black Hills. On the recommendation of a scientific and scholarly commission, several of the Native American sites were added over Roosevelt’s tenure and under

his successors William Howard Taft and

Woodrow Wilson.

This new category did not require

individual action by Congress and Monuments were created from land on military reservations, National

Forests, and Interior Department lands

at least theoretically available for Homestead. Sometimes those proclamations clashed with

local interests, especially mining and they became controversial.

Despite the expansion and a sharp spike in visitors as some parks

became accessible by bus and automobile, management was still

haphazard. Were the Army was not in de

facto control, management and care was left to a hodge-podge of contractors and locally recruited employees often without much experience or expertise. Secretaries of the Interior under Taft and

Wilson; the powerful American Civic

Association, a pillar of the

establishment; landscape architect

Fredrick Law Olmsted; Representatives William

Kent and John E. Raker of

California; Senator Reed Smoot of Utah; industrialist and conservationist

Stephen T. Mather; journalist Robert Sterling Yard;

and California conservationist Horace M.

Albright led a campaign for the establishment of a new agency under the Department of the Interior with the authority

control, manage, and plan development of the National Parks. They got support from the Army, which was

busy chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico on one hand and faced with the possibility of eventual entry into the Great War in Europe on the other was eager to shed its responsibilities in the

Parks.

| First Park Service Director, Stephen T. Mather |

Congress finally acted and Wilson

signed the National Park Service Organic Act on August 25, 1916. It brought

all of the National Parks and some National Monuments under the control of the

new agency. Stephen Mather, as expected

was named the first director of the agency with Albright as his

deputy. Heading the list of his early

achievements was overseeing the creation of Grand Canyon National Park in

1919 against vehement opposition from mining interests.

Mather was respected enough as a non-partisan figure to be

held over in the Republican administrations of Warren G. Harding and

Calvin Coolidge. Miraculously, he

insulated the Park Service from the corruption scandals that

engulf Harding’s Interior Secretary Albert Fall and other

agencies of the Department. Mather

created a professional civil service organization, increased the numbers

of parks and national monuments, and established systematic criteria for

adding new properties to the system.

Despite battle with bi-polar disorder which sometimes left him so

depressed he was unable to work, with the close support of Albright Mather was

able to convince Congress to make the first expansions of National Parks in the

East when the Shenandoah

and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks were authorized in 1926. He

suffered a stroke in 1929 and had to retire, dying less

than a year later. Albright continued

his work in the Hoover administration.

A big part of the building the new

Park Service was the creation and development of Park Rangers to replace the Army and assorted patronage hires and private

contractors who had managed, protected, and policed the Parks. They took their name from Roger’s Rangers of the French and Indian Wars and futile search for the elusive Northwest Passage, but were inspired by

Harry Yount, the Gamekeeper of Yellowstone National Park in 1880 and ’81 who patrolled for poachers and acted as a guide for tourists and an escort for visiting officials. Yount

told his boss Interior Secretary Carl Schruz before he resigned in frustration

at being overwhelmed by a job to big for a single man, that the Park needed to

“…be protected by officers stationed at different points of the park with

authority to enforce observance of laws of the park [and for] maintenance and

trails.”

|

| Gerald R. Ford as a Seasonal Ranger at Yellowstone. |

Mather described the plethora of duties and responsibilities

of the Rangers:

They are a fine, earnest, intelligent,

and public-spirited body of men, these rangers. Though small in number, their

influence is large. Many and long are the duties heaped upon their shoulders.

If a trail is to be blazed, it is “send a ranger.” If an animal is floundering

in the snow, a ranger is sent to pull him out; if a bear is ranger.” If a Dude

wants to know the why, if a Sagebrusher is puzzled about a road, it is “ask the

ranger.” Everything the ranger knows, he will tell you, except about himself.

The earliest Rangers

wore the civilian gear of a woodsman,

hunter, or logger. Senior Rangers, Park Superintendents and the like, could be distinguished mostly by wearing a tie, polished boots, and

a hat without holes in it. Soon they adopted military style uniforms, kaki

and later green with the same

soft felt campaign hats as the Doughboys of World War I. By the late

20’s the uniform was made sharper for public duties—a stiff brimmed gray Stetson replaced the soft felt, green jacket and trousers, and a gray shirt

with a tie. Basically the same recognizable and iconic uniform

is still in use today for both male and

female Rangers. Summer uniforms now feature gray short sleeve, open collar shirts and straw versions of the Stetson or green baseball style caps for work details.

The election

of Franklin D. Roosevelt heralded a new era for the Park Service. In one of his last major acts Herbert Hoover

signed the Reorganization Act of 1933

which gave his incoming successor the power to reorganize the Executive Branch of the government. Later that

summer Albright brought the FDR a

proposal for sweeping changes to his agency. Roosevelt approved two executive orders not only transferred

to the National Park Service all the War

Department historic sites—battlefields,

some cemeteries and fortifications—but also those National

Monuments which had been managed by the Department

of Agriculture. In addition the

monuments and parks around Washington

D.C. which had been run by an independent office were brought under

the Department including the Washington

Monument, Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, the National Mall, Lafayette Park, and the grounds

of the White House. For the first time Park Rangers were

active and interacting with hundreds of thousands of visitors a year in an urban setting. In the wake of the reorganization the Park

System expanded by adding 12 natural areas in 9 western states and Alaska and

57 historical areas located in 17 predominantly eastern states and the District

of Columbia.

It was

Albright’s last hurrah at the helm.

Roosevelt appointee Arno

B. Cammerer, a career department official and former top aide to both Mather and Albright took over. He would remain in charge until 1940 despite

clashes with Interior Secretary Harold

Ickes, a top New Dealer with a more political agenda. He began to survey and record historic

sites and buildings outside the

existing parks, and worked with Congress to pass the Historic Sites Act as well as a law establishing the National Park Foundation to privately raise funds for Park acquisitions and improvements. Several more

sites of all types were added including many in the East and closer to heavy

population centers.

|

| A CCC crew constructing a small timber trail bridge in Acadia National Park in Maine |

The Parks

really got a boost when the New Deal came

into full swing. Park improvement projects including road and bridge construction, trail

development, visitors centers,

campgrounds, piers and docks, and interpretive museums were built by the Works Projects Administration (WPA) and especially by the Civilian Conservation Corps. At the program's peak in 1935, the

Service had 118 CCC camps assigned to National Park System areas, with approximately

120,000 enrollees and 6,000 supervisors. All of that work really transformed many Parks and the improvements

can still be seen and used today.

As a result

of greater access to the parks by automobile

and the increase in facilities within easy reach of many citizens, over the

Depression years Park attendance

jumped from two million annual

visitors in 1933 to more than 15

million in 1940. In fact by stimulating travel and tourism, the National Park system

contributed to the long climb to

economic recovery.

Cammerer

suffered a heart attack in 1940, many said brought about by his clashed with

Ickes and had to resign. He was dead a

year later. His replacement Newton B. Drury, and advertising executive and leader of the

Save the Redwoods League was the

first Director not to come up through the ranks of the Park Service. He was immediately faced with the reality of World War II mobilization and a massive

shift in spending priorities by the Roosevelt administration. Money for further expansion of the system evaporated. The CCC wound down and was eliminated, the young

men one destined for its ranks drafted into

the armed services instead.

Much of Drury’s

time was spent eking out the most of

his diminishing resources, fighting

further cuts in Congress, dealing with labor

shortages as his Park Rangers and civilian employees were syphoned off into

the military or into industrial defense

production. There was also a constant battle to keep the Parks from

being invaded for their resources in

the name of defense production including mining across the Southwest and lumbering.

The military also pressed for use of Park lands for training camps, air fields, and even artillery and bombing ranges.

Even after

war’s end, the mindset of the Truman administration

was far less friendly to traditional conservation

values and wanted to use Park lands more like the National Forests which were managed more for their resources than

for their preservation as natural places.

Money for expansion and maintenance did not come flooding back from the

Federal Budget. At the same time after a lull in the war

time rationing years, Americans were

hitting the roads again in droves and the National Parks and Monuments were a

popular destination. Annual visits

soared again and the parks were unable to update to accommodate them, or even

to adequately maintain their infrastructure.

In 1951 Drury

clashed with Interior Secretary Newton

B. Drury over his support for the Echo

Dam project which would have flooded

canyons of the Colorado River in

Dinosaur National Park. It was part of a proposed system of dams

on the Colorado and Green Rivers for

hydro-electric generation. Drury resigned in protest and helped rally massive

opposition to the project from across the Conservation movement. After year of protest, Congress removed the

Echo Canon project but approved the construction of the other dams in the system. 1956 legislation forbad building such

projects in the future on Park Land. It

was seen as an early victory of a resurgent conservation movement.

After a short

interim, Conrad L. Wirth became

Director in December of 1951. He was

park professional and a member of the Park service since reorganization. He found the incoming Eisenhower administration mildly friendlier to the Park System and

conservation concerns as the economy shifted

into an unprecedented extended

boom. Wirth began his term with a

systematic survey of Park Service facilities and found them badly neglected and

inadequate to still soaring public usage.

As a result

in 1955 Wirth proposed a decade-long

program of capital improvements,

to be funded as a single program by Congress aimed at

modernizing all Parks properties by the Service’s 50th Anniversary in 1966. The program, dubbed Mission 66 represented the most significant re-allocation of

resources since the Reorganization and the first capital development since the

CCC days. It also represented a change

in philosophy.

The Park Service

wanted to create facilities that were modern and up to date, abandoning the

rustic style that had been its trademark.

New visitor’s centers and museums were sleek, low-strung, and apt

examples of Mid-Century modern design

and architectural tastes. A controversial

shift from showcasing nature to accommodating visitors who were increasingly

using the parks as family vacation

destinations led to road and highway building in the parks and the

development of some large scale resort-like

developments reaching the proportions of new towns in popular destinations

Parks like Yellowstone, Grand Teton,

and Sequoia.

The project

also involved for the first time large scale urban redevelopment. In St. Louis, Missouri the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

cleared 40 blocks of crumbling warehouses,

business, and residential slums for

a landscaped open space to showcase

the Gateway Arch, purposefully designed

tourist attraction monument. Similar urban

clearance razed hundreds of buildings in Philadelphia,

several of them of historic significance

to create the Independence Mall to

better display a resorted Independence

Hall at the heart of the Independence

National Historical Park.

Somewhat

ironically considering the destruction of historic building in these projects,

Wirth’s revival of the Historic American

Buildings Survey which had been suspended since the War years let to the

creation of the National Historic

Landmarks and National Register of

Historic Places programs in 1960.

An emphasis

on developing recreational use of the Parks spurred development of National Seashore and National Recreation Area programs and

the additions of Cape Cod, Point Reyes, Fire Island, and Padre

Island into the system.

Wirth retired

in 1963 as his grand project neared its culmination. He recommended his deputy, George Hartzog as his successor. He started as an attorney for the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management and moved over to the Park Service in

1945. He had been superintendent in charge of development of the Jefferson Expansion

park in St. Louis. He served under an

administration even friendlier to conservation than Eisenhower’s. Interior Secretary Stuart Udall was an enthusiast for natural preservation. Together they pushed for the development of included

62 new parks, the adoption National

Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and the Bible Amendment to the Alaska

Native Claims Settlement Act that led to establishment of the Alaska parks. He also aggressively pushed forward with the

creation of urban parks, especially Indiana

Dunes National Lakeshore near Gary,

Indiana and Chicago.

In 1969 under

the Nixon Administration budget, the

Park Service faced its first significant cuts in years. Hartzog argued that the cuts were so severe

that they would force cutbacks in service to the public. To prove his point he closed popular

facilities such as the Washington Monument and Grand Canyon National Park for

two days a week arguing that he couldn’t afford full staffing. The move inconvenienced and angered tens of

thousands of tourists and enraged members of Congress and the conservative

press who called the political gambit the Washington

Monument Syndrome. None the less, it

worked, and public pressure resulted

in the restoration of the cuts. But an

outraged Nixon forced Hartzog to resign.

It

was the beginning of a long struggle between the rising expectations of the

rapidly growing Ecology Movement on

one hand which was supplanting traditional conservationism and rising conservative hostility on a number of

fronts. Conservation and the Parks had

generally enjoyed bi-partisan support

but the rise of environmentalism, which

was evidenced in changing priorities and educational programs by the Park

Service, was seen as an attack on

American industry. Demands were made to

open the Parks again for extractive

exploitation, especially oil and

gas exploitation and proposals that

would have leveled much of the Colorado Rockies for oil shale while environmentalists were

demanding ever-stricter protections from damage done to parks by even peripheral development.

Regan Administration Interior Secretary

James Watt of Wyoming, was a born again

Christian who believed that the end

of days was imminent. In his view,

with the apocalypse looming there

was no need to conserve resources,

but people had a full right to consume

as much as they desired since there would be no human inheritors of the Earth.

I am not kidding, Watt really

professed to believe that and made it the cornerstone

of his policy, which put him at odds

with the non-political, professional management of the Park System. Luckily public outrage and Congressional

opposition were enough to block most of Watt’s most ambitious plans, but the

battle was far from over.

| The Lincoln Memorial and Park Service properties across the country were closed to visitors during the Government Shutdown of 2013. |

The

Park Service became an annual prime target of Congressional budget hawks of both parties who sought

to slash discretionary spending in

pursuit of the ever elusive balanced budget

and debt reduction. Budget lines actually fell in some years

or more often were frozen failing to

keep up with inflation and resulting

in massive de facto cuts. Funds for

land acquisition were slashed to near zero, capital projects halted, and maintenance

deferred. Meanwhile infrastructure in the Parks has

taken a beating to the point that roads and bridges have had to be closed as

unsafe. In this fiscal year, after a slight uptick, $90 million in general deferred

maintenance and $28 million in road and transportation repair, the total deferred

maintenance stands at an estimated at nearly $12 billion dollars with no relief in sight unless Republicans lose control of Congress.

Beyond

penny pinching, two other issues have made conservatives increasingly hostile to the Park Service. It turns out that National Parks are teaching

visitors, including children that evolution over eons and millennia is accepted science. That means the Earth is more than 6000 years

old and that humans evolved from earlier

species of apes. Worse, the service

acknowledges global climate change

and has developed special educational

programs to demonstrate it. That

makes the Park Service a prime target of the war on science.

|

| The war on public land nearly got hot early this year when armed alleged Patriot Militia siezed the Malheur Wildlife Refuge. |

Finally,

a one-time fringe theory that the

Federal Government has no right to

retain public land, including Parks and that they should be turned over to the states, or even to counties. This has dovetailed with the libertarian and Tea Party horror at the supposed “tragedy of the commons”. At

its most benign it has resulted in

moves by the House of Representatives to

sell all or parts of the National

Park system along with Forest Service and other public lands and in the state

of Utah officially demanding Federal

lands be turned over to the states. On

the more extreme level it played out in the armed seizure of the National

Fish and Wildlife Service managed Malheur

National Wildlife Refuge near Burns,

Oregon by right-wing militia earlier

this year.

Countering

this trend Barak Obama has been the

most supportive President of the Park Service since Lyndon Johnson and has dueled repeatedly with Congress about

it. In 2013 the Service was front and

center in the government shutdown crisis

when much like Hartzog back in 1969 Director Jonathan Jarvis shut down

monuments on the National Mall and other Park attractions nationally. Even when the crisis passed and the

facilities reopened, thousands of

employees were furloughed.

Meanwhile

the President used his authority to create new federally protected land in the

system more frequently than any President since Roosevelt. He has authorized 20 new Park System units

and approved 5 more pending land acquisitions.

Many of these sites were highly controversial. Many of these sites reflect an interest in

broadening the historic scope of Park Service sites to include more minorities

and urban experiences. Additions under

Obama have included Castle Mountains

National Monument in the Mojave

Desert that checkmated further development

of a devastating open pit gold mining

in the area; the unique Manhattan

Project Historic Park with separate units in Tennessee, New Mexico, and Washington

state; the Pullman National Monument

in Chicago; the Valles Caldera

National Preserve in New Mexico; the World

War I Memorial in Washington, D.C.; the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in Ohio; the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument in Maryland;

the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument

in California; the Paterson Great Falls

National Historical Park, a significant industrial and labor history site

in New

Jersey; the Fort Monroe

National Monument in Virginia;

the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

in D.C.; the President William Jefferson

Clinton Birthplace Home National Historic Site in Arkansas; and the Port

Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial; and

just days before the 100th anniversary the

Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in Maine, now the Monument in

area east of the Mississippi.

Yet

the struggle with Congress to adequately fund the Park System is ongoing. Which is why the Park Service and the Obama

Administration has so heavily promoted the

centennial of the Park service over the past year, kicking off with the annual Independence Day Concert and fireworks

broadcast from the National Mall last

year. It has been a full year of special events and programs at Park facilities

across the country, television public

service announcements, social media promotions, magazine and newspaper

articles, coffee table picture

books, documentaries, and a special series of postage stamps. It has been

an unprecedented public relations push aimed

at getting public support and neutralizing

right-wing anti-park propaganda. And it all culminated with free admission to all parks, special events

around the country, the big show at Yellowstone

Park, and a living Park Service logo

by employees near the World War II

Memorial in Washington.

Hey,

I was impressed.

No comments:

Post a Comment