|

| Sgt. Mauldin on the job. |

When I was a boy I was obsessed with

the great event of my parents’ life time—World War II. It was hard not to be. Almost every house I ever visited had at

least one framed photo of a handsome young man in uniform proudly

displayed. Sometimes more. Husbands,

brothers, fathers. Most came

home. Some didn’t

The survivors of those photos were still mostly youngish men in the prime of their lives—my father and the fathers of almost all of my friends. They were serious, hard working men. They were very busy doing things, sometimes big things. To a man those I knew best, my father and uncles, could hardly be made to talk about their experiences. If pressed they would say, “Well, I was in Europe for a while.” Or, “I was a Seabee.” Further details

were seldom forthcoming.

They belonged to the Legion or the VFW, but seemed neither super-patriotic

nor querulously eager for the next war. They took

comfort in being around other man who had been there, but they distrusted the occasional braggart and blowhard

at the bar. Their contempt for that ilk was summed up

years later in a Bill Mauldin

cartoon in the Chicago Sun Times showing

one of the bellicose Legion leaders of the Vietnam era beginning and ending his World War II

service, “folding blankets in Texas.”

For real information on what our dad’s did in the war, we had to turn

to our mothers. Mine was glad

to share her meticulously kept scrap

books with photos, postcards, newspaper clipping, maps, V-mail letters, and even un-used

ration stamps. And she dug out the

well buried footlocker in the basement chocked full interesting stuff. I claimed a khaki overseas cap,

which for a season or two I wore

everyday in lieu of my customary

cowboy hat, a web belt, canteen, mess kit, ammo pouches,

a gas mask bag, and a helmet liner. I was outfitted well for the endless

games of war the neighborhood boys

played in backyards among hedges and window wells.

On Sunday afternoons I was glued to the TV documentaries about the war that were still a staple of the air—the Army’s The

Big Picture, Victory at Sea, Silent Service, and most episodes of Walter Cronkite’s The Twentieth

Century. And then there were the

old movies that played on the daily movie matinee show which came on

just as I got home from school. I

thought I knew what war was about.

But of course I didn’t know squat. Until I

found in my mother’s bookshelves

well thumbed editions of This

is Your War, a collection of

columns by the great war correspondent

Ernie Pyle and a couple of

collections of Bill Mauldin’s Willie and

Joe cartoons for Stars and Stripes.

Both Pyle and Mauldin rose to fame covering the brutal, unglamorous Italian campaign as troops slogged slowly north through the Boot against stubborn German resistance, treacherous

mountainous terrain, rubble strewn

street fighting, supply shortages,

and often incompetent leadership. So much for Winston Churchill’s “soft

underbelly of Europe.” Fighting

there dragged on after it was relegated to a side show and Allied troops, liberated at last from the Normandy

beaches, were racing across France far

to the north.

The two both told about the war from

the front line perspective of the G.I. dogface—exhausted, bitter,

cynical, stripped of all illusions of

glory, immune to patriotic exhortations, and suffering as much at the hands of clueless generals and idiot second lieutenants as from the usually unseen Nazis. Pyle drew the picture with words. Mauldin just drew the picture.

And remarkably, he did so in the official GI newspaper Stars and Stripes as a sergeant in the Army he chronicled. Willie and Joe were his creation to represent the lives of the grunts on the

ground. They were unshaven, slovenly, and perpetually exhausted. They looked in those drawings like old men. But Mauldin, who was only 22 and looked years

younger, pointed out that Willie and Joe were the same age he was. War did that to them.

The old spit-and-polish brass hated Mauldin and often tried to get him banned from the paper or refused to issue passes to their front line

units—where he went anyway,

regardless of any stinking passes. General George Patton called him to his

headquarters and threatened to have him arrested for disturbing morale. Dwight

Eisenhower had to personally intercede

with orders to leave Mauldin alone. He thought the comics helped his men “let

off steam.”

| Stuff like this jab a Old Blood and Guts got Mauldin personaly called on the carpet by George Patton. |

Mauldin was born on October 29, 1921 in Mountain

Park, New Mexico. His family was no strangers to the military.

His grandfather was a cavalry scout

in the campaigns against the Apache.

His father was an artilleryman

in World War I.

The family moved to Phoenix, Arizona where Mauldin finished

high school and became interested in art. He enlisted

in the Arizona National Guard, but was able to go to Illinois where he attended

classes at Ruth VanSickle Ford’s Chicago Academy of Fine Art.

He never completed his studies.

He was called up from the

Guard to active duty in 1940. He was assigned to the 45th Division, the first

all-Guard unit activated prior to America’s

entry into the war and made up

units from New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado

and Oklahoma including many Native Americans.

Mauldin was a good soldier despite his almost childish appearance. He advanced to the rank of sergeant

quickly and began contributing cartoons

to the Division newspaper. While still training stateside he created Willie and Joe, based largely on his best friend and himself. When the unit deployed overseas he was assigned to the Division Press Office. He

did not consider that to be behind the

lines duty.

When the Division landed in Sicily in July of 1943 for its first

combat operations, Mauldin was right there with the front line infantry. He stayed there. He was with them again on September 10 when

the Division landed at Agropoli and Paestum, the southernmost beachheads of the Salerno

campaign. Thus began the long,

grinding inch-by-inch slog up the length of the Italian Boot.

Mauldin’s cartoons were being

reprinted in Stars and Stripes and in

February 1944 he was transferred to the

Army newspaper, issued a Jeep

and given pretty much a carte blanche to

cover the front as he thought best. His reputation

among GIs was high and everywhere he went they welcomed him even if officers

were mostly uniformly mortified.

Recognition that he often took

the same risks as infantrymen won him credibility,

especially after he was wounded by

mortar fire while visiting a machine

gun crew near Monte Casino.

| Bogged down hopelessly in Italy, Willie and Joe were a tad cynical about all of the glory of D-Day. |

He returned to the front and his drawings, which were now also being circulated by the Army to civilian papers

in the States. The Brass felt that

the cartoons would make clear to the public the realities of the war and explain the slow pace of advance in Italy

to a public which expected quick

victories.

Mauldin was awarded the Legion of Merit, an award usually given to field grade officers in combat operations. At the end of European operations, Mauldin wanted

to have Willie and Joe killed on the last day of combat, a final thumb of the nose to the futility of

war. The horrified Brass quickly nixed that idea.

Back

in the States and out of the service,

Mauldin found himself something of a celebrity. He had even made the cover of Time.

He won the Pulitzer Prize in

1945. His first book Up Front, one of the books I purloined from my mother’s selves, was

a best seller. It contained many of the best Willie and Joe

cartoons along with no-holds-barred

essays that stripped all glory from

war.

A defiant liberal, Mauldin

found it difficult to fit into an

America in the throws of Red Scare paranoia and hardening conservatism. His attempts to establish a career as an editorial

cartoonist were stymied as newspapers shied away from “controversial content” especially when he echoed the views of the American

Civil Liberties Union and its opposition

to witch hunts, black lists, and attacks on individuals for their political opinions.

He tried to transition Willie and Joe to civilian

life and chronically the hard times

they had fitting in. The public wasn’t interested.

| Two GIs lent gritty credibility to John Huston's The Red Badge of Courage--Audie Murphy and Bill Maulden. |

Discouraged,

Mauldin turned to illustrating magazine

articles and books. He even tried

his hand at acting, appearing

with another youthful looking veteran,

Audie Murphy in the Civil War film, The Red Badge of Courage.

Mauldin also struggled with his personal life.

He married three times and fathered eight children.

In 1956 at the height of the Cold War Mauldin ran for Congress in a rural Upstate

New York District as a peace Democrat.

He campaigned hard and

was personally well received by local

farmers—until his foreign policy

positions failed to match to staunch

conservatism of the district.

|

| Mauldin was a fighting liberal in a conservative Up State New York district when he ran for Congress. He got his head handed to him. |

In 1958 he finally got steady work as staff

editorial cartoonist for the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch and the national syndication that went with

it. Ironically Mauldin’s still

struggling career got a boost when he

won a second Pulitzer Prize 1n 1959 for

a cartoon that was acceptable to the

anti-Communist crowd. It pictured Boris Pasternak, author of Dr Zhivago in a Soviet Gulag asking a fellow inmate, “I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was

your crime?” In fact the cartoon was in line with Mauldin’s consistent defense of the rights of free

speech and civil liberties.

Mauldin moved in 1962 to the Chicago

Sun-Times , Marshal Field’s

liberal challenger to Col. Robert

McCormick’s hyper-conservative Chicago Tribune. It gave him a supportive home for outstanding

political cartooning for the rest of his career. Mauldin’s editorial page panel was one of the big reasons I became a

dedicated reader of that paper for years.

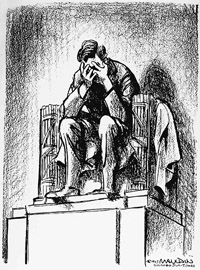

Among his famous Sun-Times cartoons is the picture of Lincoln seated in the Lincoln Memorial burring his face in his

hands the day after the assassination

of John F. Kennedy—which inexplicably failed to win a third

Pulitzer. He was a bitter opponent of the Vietnam War and supporter of anti-war protestors. His cartoons during and after the Democratic Convention in Chicago in

1968 featured Mayor Richard J. Daley as

a Keystone Kop, which made Hizonor apoplectic.

|

| Mauldin captured the mood of the country in his iconic drawing the day after the Kennedy Assassination. |

Mauldin retired in 1991. He was missed.

He occasionally contributed a cartoon and did several interviews. He entertained old friends and admirers.

But his fine, sharp mind was fading.

Suffering from Alzheimer’s

Disease Mauldin was badly scalded in

bath tub accident and died in great

pain in Newport Beach, California on

January 11, 2002. He was buried with so many of his fallen comrades

at Arlington National Cemetery.

Willie

and Joe endure.

Over the years I've met many folks of our vintage who can say, utterly without irony, "I learned everything I know about World War Two from my parents' copy of 'Up Front'."

ReplyDeleteDiggitt, I've learned a lot more since, but in my case it was an aunt who was a WAC in the Occupation of Japan who had 'Up Front'.

ReplyDelete