|

Ernie Banks connects for the long ball at Wrigley Field.

|

Today would have been Ernie Banks 89th birthday if he had

made it. But he didn’t. He died in a Chicago hospital on January 23, 2015.

When the news his passing came it

was a shock to many Cubs. It probably shouldn’t have. After all he was nearly 84 years old. It’s just that he seemed so ever youthful, not just in those memory pictures we had in our head of

his days on the diamond, but in the

frequent glimpses we would get of him on TV

at fan events or in interviews. No matter how gray or sparse his hair

became, how lined that lean face, he seemed boyish, bursting with enthusiasm and, yes, ready to play two.

Banks was, bar none, the most beloved player in the long history of

the Chicago National League franchise. He was the only longtime Cub player not to draw contempt and scorn from hard core White

Sox fans. Beyond the playing field

his gentle demeanor and graciousness to fans and the press endeared

him to the whole city. His status as an icon of a losing franchise almost obscured

his real accomplishments on the

field.

But as an obituary in the New

York Times, hardly a Second City

boosting cheerleader, pointed

out, Banks was, “the greatest power-hitting

shortstop of the 20th century

and an unconquerable optimist…”

Banks was born on January 31, 1931,

in Dallas, Texas, the second oldest

of 11 children of a warehouse worker

and his wife. His father, Eddie Banks had played semi-pro ball and encouraged his athletically inclined son to take an

interest in the game. Ernie was not much

interested and at first had to be bribed

to play catch with the old man. Part

of it was that he had few opportunities to play organized baseball. There

was no Little League for Texas Black boys in those days and Booker T. Washington High School did

not have a team. Instead he lettered in track, basketball, and football. The closest he could come to baseball was

playing softball in summer church leagues, and for a season with

the semi-pro Amarillo Colts.

|

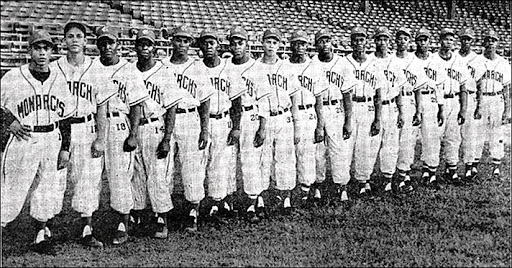

Ernie Banks, second from right, with the 1953 Kansas City Monarchs.

|

Still after graduating he somehow

managed to catch the attention of the Kansas

City Monarchs, the most prestigious

franchise in the Negro American

League. Some accounts give credit to

a scout who was friendly with his

father, others to legendary player Cool

Papa Bell. Maybe it was both. But in 1950 he was signed and playing for the Monarchs.

Bank’s fledgling baseball career was

cut short when he was drafted into the Army in 1951. He suffered a knee injury during basic training which would haunt him later in his career. He was attached to the 45th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion at Fort Bliss where he was a sharp enough soldier to be made the

unit’s flag bearer. During his months at Bliss he was able to

sub occasionally with the Harlem

Globetrotters operation, usually appearing in the uniform of the

perpetually loosing Washington

Generals. After that he was

stationed in Germany.

Upon his discharge from active duty,

Banks rejoined the Monarchs. His time

with the team was his university of

baseball. He learned and mastered

quickly all of the fundamentals of

the game. In no time at all he was a star player. So good that he was attracting attention from

Major League scouts who finally ready to stock their teams with Black

talent. He finished the 1953 season batting for an impressive .347 average.

The Chicago Cubs snatched him up and he would wear the blue pinstripes for the final games of

that season.

Despite the opportunity, Banks was

loathe to leave the Monarchs which he considered his home. He thought about asking the team not to sell

his contract. That is the kind of loyalty that in the end he transferred

to the Cubs.

The Cubs, badly in need of talent,

put Banks directly into the Big League

game without any time in the minors. His debut at Wrigley Field was on September 17, 1953 versus the Brooklyn Dodgers.

|

An autographed copy of Banks's rookie card.

|

Before the game Jackie Robinson crossed the field to welcome the Cubs’ first Black

player and give him some support and encouragement. Robinson had also played for the Monarchs and

was Banks’s idol. Banks later recalled

that Robinson told him, “Ernie, I’m glad to see you’re up here so now just

listen and learn.” It was advice he took

to heart, maybe too much so. “For years, I didn’t talk and learned a lot about

people.”

His reticence to speak up on racial tensions and issues on and off

the field would later draw accusations

of being an Uncle Tom from

some. But it was not in his nature to be

confrontational and he tried hard to

make friends with everybody. Robinson

believed his early reticence in responding to abuse on the field when he first broke baseball’s color line earned him the right to

speak out and became Civil Rights

movement spokesman. Despite their

differences over this Banks and Robinson remained close.

In his first full season with the

Cubs as shortstop he paired up with

the team’s second Black player Gene

Baker at second base to form a

bang-bang double play combination. The two also roomed together on the

road. Banks hit a respectable 19 home runs and had 71 runs batted in. It was good enough to finish second in National League Rookie of the Year voting.

|

Banks turning a bang-bang double play at short stop.

|

Banks really took off as a dominant player in 1955, his second

full season, after he switched to a lighter weight bat increasing his bat speed. Thanks to strong wrists and a sharp eye for

a fast ball, the tall, slender

(6’1”, 180 lbs.) shortstop became a genuine power hitter and slugger. That season he slammed 44 round trippers and drove in 117

runs. He earned the first of 14

consecutive All Star Game appearances. His home run total was a single-season

record for shortstops and he set a thirty year record of five single-season grand slam home runs.

It was the beginning of a parade of

phenomenally successful seasons in which he was a shining star on miserable

teams. In 1956 despite missing 19

games with an infection in one hand

that took the edge off of his power Banks still hit 28 home runs, had 85 RBIs,

and a .297 batting average. In 1957, he bounced back with 43 home runs, 102

RBIs, and a .285 batting average.

|

Banks slamming one home at Wrigley Field.

|

Then there were the back to back Most Valuable Player (MVP) Awards—a first in National League

history—in ’58 and ’59. He hit over .300 each year, led the League in RBIs both years, and knocked 47 homers

the first year and 45 the next. In 1960

he led the League with 41 homers, earned a Gold

Glove at short stop and for the sixth time in his seven year full season career

led the league in most games played.

Banks was not only the star, but a

consistent work horse on terrible

teams. The Cubs currently have a

reputation for a fanatical fan base and

the ability to fill the seats of Wrigley Field no matter how miserable the

teams on the field. But it was not

always so. In the early ‘50’s years of

bad teams had slashed attendance. The North Side ball park frequently

resembled a ghost town. Banks gave fans something to plunk down money

to see. As Ernie got hot, the fans began

to come back. Not only that, he helped

them bond with the team, especially with children

for whom he always seemed to have time.

Banks was building a fan base

for the team that would become multi-generational.

Cubs owner P. K. Wrigley was meddlesome, eccentric, and most of all cheap.

Despite Bank’s value to the team, he was paid remarkably modestly. He

was paid only $27,000 for the ’58 season.

That did jump to $45,000 the next year and after that it rose by small

increments annual so that by the time he retire in 1971 he was making

$50,000. While those were comfortable

salaries in the days before big time

agents and skyrocketing pay, they lagged far behind Banks’ peers in the top

rung of baseball talent by as much as 50%.

Yet the star slugger never publicly

complained out of loyalty to the team and because he enjoyed an unusually close

personal relationship with Wrigley. The

two often had lunch together and in the off season Wrigley entertained Banks and

his wife at his California estate.

As if to make up for the low pay he

was handing out, the chewing gum heir advised

Banks on investments and encouraged

him to get involved in the business

world. Banks credited the advice for

encouraging him to take classes in bank

management and to enter in a variety of partnership deals in enterprises that included a car dealership. Some of the investments worked out. Some didn’t.

But Banks did make money. And he

discovered he was a personal asset to companies who wanted to polish their

images and raise their public profiles.

If he never became the great executive

he yearned to be, he did become a hugely successful public relations asset and company spokesperson.

In 1961 Wrigley made the oddest decision of his ownership. Instead of hiring a new manager he put the team in the charge of his famous College of Coaches—management by a committee of 12 coaches who rotated

between them who to be field skipper

on game day. The system worked just

about as well as you would expect.

That spring the constant shifting from left to right, a

necessary at shortstop, aggravated Banks’ old Army knee injury. The College decided to rest him at short and

put him in left field, a position he

was totally unfamiliar and uncomfortable with.

“Only a duck out of water could have shared my loneliness in left

field,” he later said. But with the help

of center fielder Richie Ashburn he

quickly adapted and made only one error in 23 games out in the cow pasture.

The College then moved him to first base, the position he would keep

the rest of his career. By May 1963 he

was good enough at his new position to set a record for most put-outs in a game by a first

baseman.

But Bank’s power began to taper off,

as did his speed on the base paths. In ’62 he had been beaned by Moe Drabowsky and

was carried off the field unconscious

with a concussion. He missed three days and bounced back

with a three homer game. But there were

lingering effects. The following year he was weakened by the mumps, a very dangerous illness in adult

men, and finished the season with 18 home runs, 64 RBIs, and a .227 batting

average. But when he hit, it was timely hitting and the team posted its

first winning season since his

arrival.

The next year, however the team was

back in the toilet. Banks was settling

into homer production in the high 20’s and still good RBI numbers. On September 2, 1965 Ernie thrilled fans by

smacking his 400th career homer.

The next year, 1965, Leo Durocher arrived from Los Angeles as solo manager with a mandate to turn the bottom dwelling, money hemorrhaging team around. Things did not go well. Banks was having the worst season of his

career. He hit only 15 homers and his

slowing on the base paths caused him to misjudge leads. The Cubs finished the season with a dismal

59-103 record.

Durocher, who spent his evenings night clubbing, let the press who

covered his colorful escapades know

that he was dissatisfied with Banks who he considered washed up. In his memoirs

Durocher complained that he wanted to bench Banks but could not because, “there

would be rioting in the streets.” Since

his past was checkered with racist

comments and altercations, there

was speculation, particularly in the Black

owned Daily Defender that

Durocher’s animosity was racially

motivated.

Banks denied it and soldiered

on. In his memoirs he wrote sympathetically of Durocher claiming he

wished he had a manager like that early in his career and maintaining that he

learned a lot from him. Despite the tense relations, Banks stayed at first

base and his numbers came back up. In

1967 Durocher even named him a player/coach. He hit 23 home runs, and drove in 95 runs

that year. The next year his home run numbers were back up to 32 and he was

awarded the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award for

playing ability and personal character. And the Cubs were finally building a decent

team around him.

The following year the famous ’69

Cubs made their legendary run for

the National League pennant leading

through much of August until a long losing

streak and a hot New York Mets

ended their run. It was the team with

the most eventual Hall of Famers of

any that never made it to post season

play including Banks, his longtime best friend Billy Williams, pitchers Ferguson

Jenkins and Ken Holtzman, and Third Baseman Ron Santo. Banks chipped in 23 home runs, 106 RBIs,

and a batting average of .253 to the effort.

It was also the last year of Ernie’s 14 year run as an All Star.

Banks hit his 500th round tripper

before a home crowd at Wrigley on May 12, 1970.

But his career was winding down.

After the 1971 season he announced his retirement in December. He

remained on as a coach for three more seasons and then had turns as a scout and in the team front office. Durocher was fired midway through the

next season.

Banks’s life-time stats speak for themselves—512 home runs, 277 of them as

a shortstop, a career record at the time of his retirement; 2,583 hits; 1,636

RBIs; and a .274 batting average. In

addition he held the Major League record for most games played without a

postseason appearance—2,528. His Cub

records include games played; at-bats, 9,421; extra-base hits, 1,009; and total

bases, 4,706.

In his post playing days Banks

divided his time between the Cubs and his business affairs. He became a partner at the first Black owned Ford Dealership in the U.S. He worked in banking, insurance, and was an executive

at a moving company. His investments paid off and he was worth

an estimated $4 million when he retired.

But the Cubs were always closest to

his heart. In 1984 when the Tribune Company bought the team from

the Wrigley family, Banks had a desk in the Front Office and a title as a Vice President for Corporate Sales. The new management unceremoniously dumped him, which was the most disappointing, even

heartbreaking moment in his life. When

fan reaction was uniform outrage,

the company charged that Banks had missed some important Sales meetings and

anonymously leaked comments to the

press likening him to “your crazy uncle at Thanksgiving.” That went over worse. Within a couple of years the team kissed and

made up. Although Banks was never again

given a front office job, he was employed as a team ambassador.

|

Bank's Baseball Hall of Fame plaque.

|

After retirement honors just kept

piling up. In 1977 he was elected to the

Hall of Fame in his first year of

eligibility. In 1982 the Cubs

retired his number 14, the first

player so honored, and flew a flag with the number from the left field fowl poll. It was five years before another player was

so honored. In 1999 he was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team

and the Society for American Baseball

Research listed him 27th on a list of the 100 greatest baseball players.

In 2008 Banks became the first Cub player to be honored with a statue outside Wrigley Field.

In 2009 Banks was named a Library of Congress Living Legend, an

award in recognition of those “who have made significant contributions to America’s

diverse cultural, scientific and social heritage.” On August 8, 2014 President Barack Obama draped the Presidential Medal of Freedom around

Banks’ neck in a ceremony that also honored former President Bill Clinton, Oprah

Winfrey and 13 others. Characteristically,

Banks responded with a generous gesture that surprised and touched

everyone. He presented the President

with a bat given to him by Jackie Robinson, Obama’s treasured boyhood hero. Experts speculated that a bat of that provenance—Robinson, Banks, to

Obama—instantly became probably the most

valuable piece of baseball memorabilia

in history.

| |

|

All of these awards and honors paled

against the love and affection felt for Mr. Cub by former teammates and fans

alike. When word of his death spread,

fans flocked to Wrigley Field which was blocked by chain link fence for reconstruction, leaving flowers, candles,

baseball cards, and other tributes in heaps and piles against the fence. The Cubs had Bank’s statue, which had been

removed during construction for repainting and restoration, moved to Daily Plaza where more came to pay

their respects.

|

Posing with Mr. Cub at Wrigley Field.

|

The public funeral was at Chicago’s

history Fourth Presbyterian Church. A

memorial service was broadcast live on

WGN-TV and a processional carried

Ernie for the last time past Wrigley Field.

No comments:

Post a Comment