On January 11,

1759 the first life insurance company in the Colonies was founded in Philadelphia. It was one of the few innovations in the City of Brotherly Love that Benjamin

Franklin did not have his fingerprints

on, probably because he was in London

at the time serving as Pennsylvania’s

Colonial agent. It was left up to

the Presbyterian Synod to create the

Corporation for Relief of Poor and

Distressed Widows and Children of Presbyterian Ministers. It was what became known as a benevolent society—a corporation for

the benefit of a specific group, usually religious, ethnic, or membership

of fraternal organizations, and associations of craftsmen. It took the form of a mutual society, in which benefits were paid to widows and orphans annually

based on the number of shares owned by the deceased.

The

ever practical Presbyterians modeled

their company on the world’s first

life insurance company, Amicable Society

for a Perpetual Assurance Office, founded in London in 1706 by William

Talbot and Sir Thomas Allen. The development

of sound life tables earlier in

the decade by mathematician James

Dodgeson—the founder of the actuary

profession—made accurate calculations

of risk available. It was

called the “the basis of modern life assurance upon which all life assurance

schemes were subsequently based.”

Copycat Episcopalian priests organized their

own fund in 1769. After a lull due to civil unrest in the Colonies and the American Revolution, life insurance companies spread in the new republic. Between 1787 and 1837 more than two dozen

life insurance companies were organized, but fewer than half a dozen survived. The oldest commercial life insurance company selling shares to the general public instead of being confined

to closed groups was the Mutual Life

Insurance Company of New York founded in 1842.

On

the eve of the Civil War the Equitable Life

Assurance Society of the United States based in New York pioneered a new form of organization for the life

insurance industry based on ownership and control by stockholders, not policyholders. This form of organization made the

insurance business attractive to Wall Street and the banking industry and increasingly integrated it into interlocking financial empires.

Early

critics of life insurance complained that it was like “betting on your own death.” But inexpensive

policies sold through benevolent societies or peddled door to door in working

class neighborhoods kept poor

families from being wiped out by

funeral and burial expenses. Among the middle class policies helped keep families in their homes and

became a way of saving and building assets safely through whole life policies.

All of which stirs memories in the Old Man….

In

the early spring of 1982, I was a brand spanking new young husband and the sudden stepfather to two young daughters. I had married

the former Kathy Brady-Larsen the

previous December.

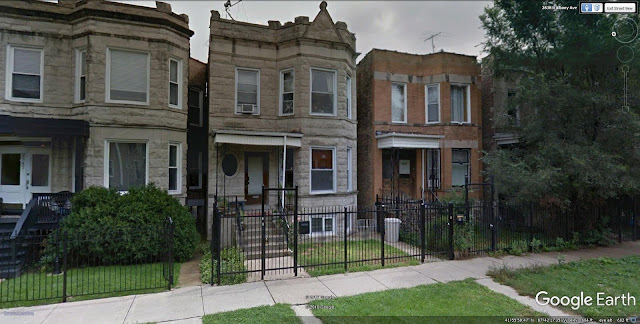

Earlier,

I had moved in to her first floor

apartment in a greystone two flat

on Albany Street just north of Diversey in Chicago. This was a significant residential upgrade for a guy who had been living in bathroom-down-the-hall single cockroach infested room with a pull-down Murphy bed. Kathy managed the building for a

young Sicilian who used to live on

the second floor and now was back in Italy

teaching English in Florence. She got a deal on the rent and her

best friend since high school moved in upstairs.

The neighborhood was a rapidly changing mix of older

immigrant Poles and other Slavs, and younger Puerto Rican and Appalachian

White families. There was a bodega at the corner of Diversey, an old fashion neighborhood candy store around the corner at the

other end of the block, and two neighborhood taverns within stumbling

distance. It was that kind of place.

I

was working as a custodian at Coyne American Institute, a trade school on Fullerton. Kathy was in customer service at Recycled Paper Products, a niche greeting card company on Broadway.

The girls, Carolynne and Heather, were 9 and 7 years old respectively and students at St. Francis Xavier School where Kathy

had previously been a volunteer gym

teacher. We were all getting used to each other. Familial

responsibilities were slowly sinking

in for me, a feckless, rootless, and utterly irresponsible 32 year old bachelor just months earlier.

One

evening as we sat watching the little TV

on the rickety stand with the rabbit ears there was a knock at the door. We were not expecting company.

I answered it. He stood neatly barbered in a long black overcoat with a neat white scarf. His dark

slacks were creased to a knife edge and he actually had on low rubbers to protect his polished shoes from the slush on the sidewalks. He carried a zippered black portfolio under one

arm. With the other leather gloved hand he proffered a business card as he greeted

me and introduced himself. The card identified

the bearer as a representative of

the Sun Life Insurance Company of Canada.

In

his rapid patter it became clear

that he knew that Kathy and I were newlyweds. This set him apart from the run of the mill insurance salesman, a

profession rife with aimless failures who quickly ran out of family and friends. This guy was a go-getter who did his homework. Either he researched marriage licenses

at the Cook County Clerk or,

more likely, he skimmed the newsletters

and bulletins of local churches and

spotted the bans printed at St.

Francis Xavier before our wedding.

I

asked him in. We were about the same age but presented ourselves in vastly different ways. He was all business

and serious about it while being cordial. He

was an up-to-date version of Robert Young’s insurance agent dad in Father Knows Best. I was shaggy and disheveled. My hair

was long and tied back in a ponytail

with loose wisps flying around

my ears. My orange goatee was long and scraggly. Bent wire

frame glasses sat askew on my nose. One eye was half closed, the

lingering effect of a case of Bell’s

palsy. My worn plaid flannel shirt was

speckled with holes burned by Prince

Albert tobacco falling from my hand

rolled cigarettes. Inevitably, I had

a can of Old Style in my hand. I

looked more like a homeless derelict than

a hot prospect.

Kathy and I

settled in with him at the dining room

table as he went through his presentation. He spread colorful brochures with smiling

families, pie charts, and what looked like a railroad timetable but turned out to be

a mortality table of monthly premiums per thousand dollars of

coverage based on gender and age at purchase of a

policy. He spoke directly only to me

although Kathy had a significantly

larger income and was really the chief

breadwinner. She was also both smarter than me and more competent dealing with the world. He would occasionally turn his best smile on

her and say something like, “you and your children will be safe and

secure.” I think he may have even patted her hand once.

Thanks to my father, W. M. Murfin, I knew

something about life insurance.

Dad was a smart man and had been a small

town bank officer before The War. But the earlier years of deprivation and near hunger during

the Great Depression had made him deeply conservative about money. It was one of the few things he took care to lecture

me about to prepare me for

the wicked wide world.

His lessons were simple. Live frugally, don’t buy on credit, and buy only what you can pay for in cash or one monthly bill. Save your money. A bank

passbook was a holy object. Regular deposits in a savings account would, thanks to the miracle of compound interest turn

into a sizable nest egg. He did not trust the stock market. If you had money to invest you put it in real estate—your own home first—and maybe your own

business. Mom had regularly bought War Bonds and if he had a little extra cash he continued to buy Series E Savings Bonds from time to

time. They were safe and predictable.

To teach my brother Tim and I these lessons, he

kept us on tight weekly allowance—I

was well into junior high school before

I saw a dollar a week—and offered opportunities to earn more for

chores like mowing and watering the lawn, burning trash in the incinerator,

and shoveling snow. Every week he or Mom took us to the First

National Bank of Cheyenne with our own passbooks to make some deposit in our own accounts. We were also given

a quarter each week to buy a Savings Stamp and when our booklets were filled, redeem them for a $25 Savings Bond.

I knew about life

insurance because my Dad always had desk

calendar emblazoned with a picture of Ben Franklin on it

from his Franklin Life Insurance agent and

leatherette covered Diary and Date book from Lincoln

National Life Insurance bearing the stamped

visage of the President. Both items sat on the cleared top of the mahogany desk in his bedroom along with a pen and pencil desk set and

an ink blotter where he sat down monthly to pay the bills.

Dad had a whole

life policy with both companies. He was friendly with both agents, which means

they shared Scotch on the rocks at local watering holes after work, long businessmen’s lunches, and

occasionally went out with their wives to some local affair. Neither policy was worth more than $5000, but

Dad considered them good investments.

Dad took time to

explain it to me. You could buy a lot more term life coverage for the money, but at the end of the term you had nothing. When your whole life policy matured you got the whole face

value in cash. With whole life your

premium stayed level from the

beginning of the policy until its maturity, typically 20 years. Term life premiums escalated rapidly

with age. While it was in force, your

whole life policy could not be canceled if your health deteriorated while you might not be able to renew term life with a bad health

report.

Finally, and this

was important to Dad, if need be you

could borrow against the principle in your whole life policy at low interest and few if any questions asked. In fact, Dad did just that to

start his travel industry public

relations company, W.M. Murfin &

Associates after he left the Wyoming

Travel Commission in 1963. The

Associates never materialized and the Highway

20 Association that he created was his only client. Eventually he added the Chicago and Detroit Sports,

Travel, and Vacation Shows before going to work for them full time and

moving us to Skokie.

All of Dad’s advice

no doubt served him well. But much of it

was already obsolete by the early

‘80’s. Raging inflation and sagging

interest had destroyed the value of traditional passbook savings accounts. Interest was no

longer compounded weekly or monthly as promised in the ‘50’s but quarterly at best. Leaving

money in a savings account meant it was actually losing value. It was hardly better than putting it in a coffee can and burying it in the backyard. Ditto for the

value of low yielding Savings Bonds which also heavily penalized cashing them in before maturity. Social changes made establishing credit absolutely essential

to daily life. You could no longer rent an apartment if you had

not borrowed and made payments. Kathy and I actually had to borrow $500

from a consumer finance company at a

high interest rate just to pay it off to

establish credit before we broke down and got credit cards.

The same was true

of most of the old advantages to whole life.

But I was too stupid to know

better. Instead, I listen to the young

agent repeat, almost word for word, all of the points my father had emphasized

years earlier. I found myself nodding along. Kathy quickly realized I was hooked.

She wanted me to feel like I was responsible father but was nervous about the relatively high

monthly premiums. She convinced me to at

least not rush into signing on the dotted line but to take time to considerer it. I shook

hands with the agent and said I would be in contact with him.

I called Dad for advice. He was living in retirement in Kimberling

City, Missouri with the cheerful former

caretaker for my chronically ill

mother Ruby who had died the year before.

He was flattered to be asked

for advice and a little impressed with

his feckless son for even

considering the future. I had never

before given much thought past my next

paycheck—if I had one coming. He

gently reconfirmed his belief in whole life.

After a couple of days,

I phoned the agent. I had to get a superficial physical from my doctor to attest to my clear medical history and good

health. The next Saturday I came into

his small office on Belmont where I

signed the policy, designated my

beneficiaries, and wrote my first premium

check. I purchased a $20,000 policy

which was all we could afford and then some.

The agent gave me a policy several

pages long with riders, and a plastic wallet to keep them

in. He also gave me a nifty zippered portfolio with

pockets, a yellow legal pad, and ball

point pen. I used that portfolio for

years.

I left the office

and stepped out into a bright, sunny

afternoon. For the first time in

my life, I felt like a grownup.

After Maureen was born and we moved to Crystal Lake, we hit a financial rough spot—not uncommon—and

Kathy decided we could no longer afford the monthly premiums, especially since

each of us had now life insurance through our jobs and another policy just to pay off our accumulated credit card debt should I suddenly kick the bucket.

We stopped making payments and lost our paid principle.

Such is life…

No comments:

Post a Comment