|

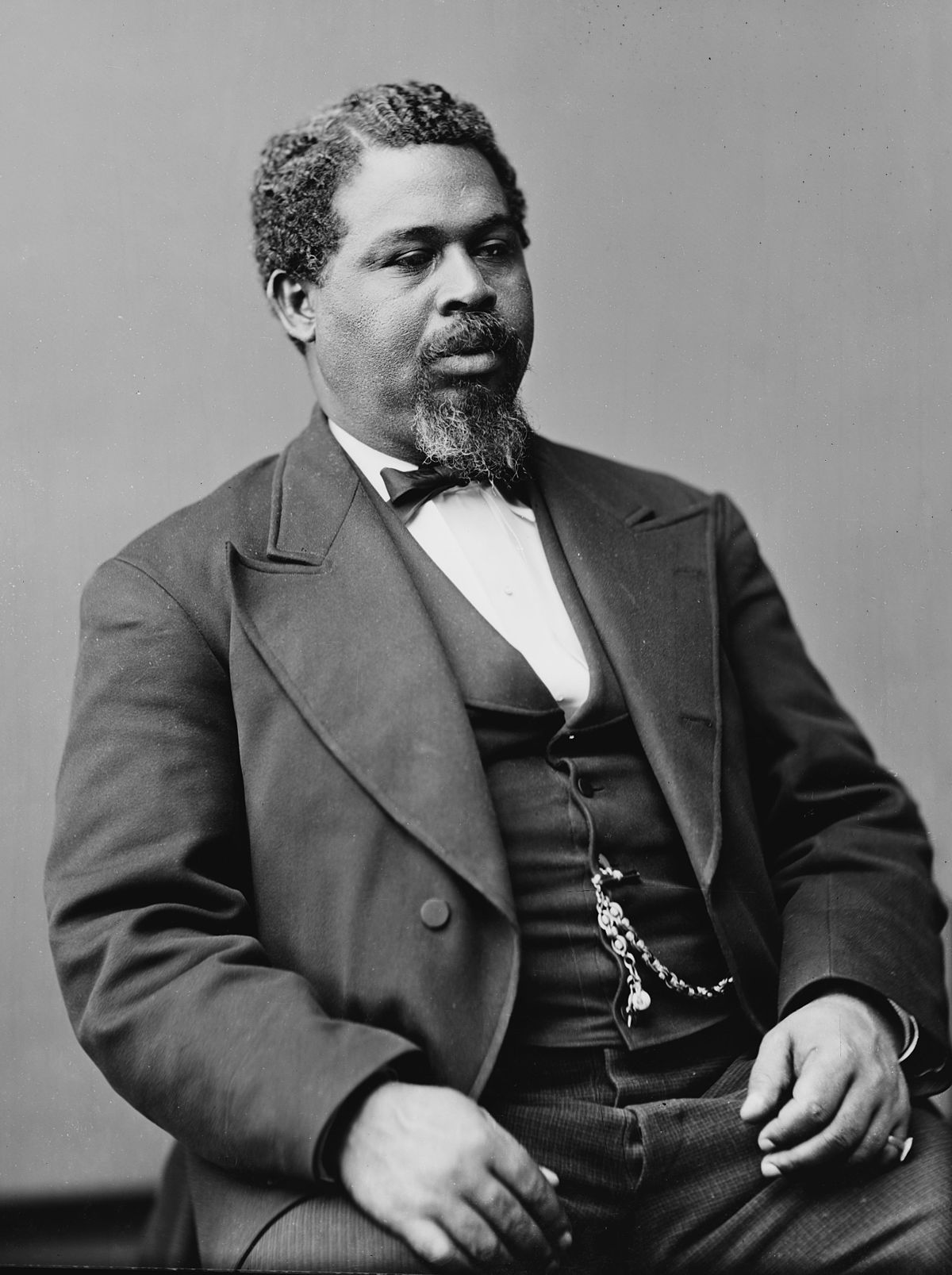

| Robert Smalls was just 23 years old when he stole the CSS Planter and delivered her, the crew, and his family to the Union. |

Note: I have written about many interesting people—and many

genuine heroes. But little remembered

Robert Smalls stands out not only for the astounding adventure that started it

all, but for rising repeatedly to epic challenges over a distinguished life. Well worth a repeat.

At

the risk of being crude, and perhaps

irredeemably sexist, there are some acts so audacious that the English

language seems inadequate to

describe them without resort to certain old vulgarities. The word I have

in mind today is balls as in big fat hairy balls. That is certainly what it took for Robert Smalls, then a 23 year old slave to calmly sail away in a Confederate

side-wheel Steamer under the guns of

at least one fortress and a Rebel flotilla to deliver the ship, cargo,

crew, and passengers to the

welcoming arms of the United States

Navy. This is what happened.

Smalls

was a skilled pilot and a trusted slave of whose owner had every expectation of loyalty

from a man raised above the drudgery

of servitude in the fields or on the docks. Robert Smalls had worked himself up from a Hotel porter to a stevedore and

finally a Wheelman in the port of Charleston, South Carolina. Various employers compensated Smalls’ master, Henry McKee of Beaufort,

South Carolina for his services and supplied

him with basic food, clothing, and housing near the docks for him and his wife—an enslaved hotel maid and their three

children. A Wheelman was the name given

to title given to Black pilots who were responsible for controlling ships as they navigated the dangerous waters of

Charleston harbor. The respected word pilot was reserved for white men doing the same job for some

of the best wages paid any workers in

the South.

On

the morning of May 13, 1862 Smalls calmly boarded the CSS Planter, a mid-sized side-wheel steamer built and launched

in Charleston just two years earlier for the costal trade. She was

currently in Service of the CSA Army

Engineer Department under the command of Brigadier General Ripley as an armed dispatch boat and transport. She was partially laden with a cargo of ammunition and explosives. With him came an

all slave crew of seven.

Earlier under cover of darkness seven passengers, five women and three children—Small’s wife and

children and the wives of other crew members—had boarded and were secured out of sight in the hold.

|

| The Planter as a Confederate supply ship and converted to a gun boat commanded by Robert Smalls in U.S. Army service. |

Smalls knew that the captain of the Planter, C. J. Relyea

would be ashore on business well away from the port area. The ship was one of several Small regularly

piloted through the waters of the harbor to open sea. Gambling that he would attract no undue attention, Small hoisted the Confederate Stars

and Bars flag, built a head of steam

and had his crew cast away from the

dock before 5 am that morning.

He would have to sail passed several armed ships in the harbor and under

the guns of a succession of shore

batteries and fortresses guarding

the South’s most important Atlantic blockade running port,

including those of the mighty former

Union bastion Fort Sumter whose bombardment a little more than a year

earlier had started the war. As he

passed each ship and fort, Small blew his steam

whistle in customary salute. Since the Planter and its Black pilot were familiar sights, she aroused no suspicion.

When

the ship broke out into open water and was beyond the reach of Sumter’s big

guns, Small hauled down the Rebel colors and hoisted a White flag. Hoping against

hope that the US Navy blockaders outside

the harbor would recognize his intentions, he made straight for the USS

Onward, an armed Clipper Ship prized

for her speed in chasing down blockade runners.

Fortunately

the Onward’s captain held his fire

and with some astonishment accepted Smalls’

surrender of the Confederate ship.

The

next day the Planter with Smalls in

command was sent on to Flag Officer Samuel

Francis Du Pont, the senior Captain

in charge of the Charleston Blockade

flotilla, at Port Royal, South

Carolina. In addition to the valuable

cargo, Smalls also brought vital

intelligence for Du Pont—news that the Rebels had abandoned defensive positions

on the Stono River allowing U.S.

forces to seize them without a bloody

fight.

|

| Smalls and members of his crew, including his brother, were celebrated in the North, especially in the Radical Republican press. |

The news of the Smalls exploit electrified the North

which was starved for good news in a

war that was, on the whole, going very

badly. Abolitionists and others who were campaigning, so far unsuccessfully, for the employment of Blacks and escaped

slaves in the war in combat roles,

were encouraged. A special

bill sailed through Congress and

sent to the willing President on May

30, to award prize money equal to half the value of the ship to Smalls

and his crew. Of that, Smalls was personally due one third. But the government undervalued the ship at $9,000—she was actually worth about

$67,000—so that Small’s portion was only $1,500. And neither Smalls or his crew were ever

awarded prize money, as was customary, for the value of the cargo estimated to be worth over $10,000 at war-time prices. Still for a former slave, the prize money

represented an unheard of fortune.

Du Pont accepted the ship into the Navy as the USS

Planter. She was first put under

the command of Acting Master Philemon

Dickenson and when transferred to North

Edisto under Acting Master Lloyd Phoenix. Smalls was retained by the Navy as pilot, prized for his intimate knowledge of coastal waters and worked on several ships,

including the Planter. As part of the South Atlantic Blockade Squadron she saw action over the summer of 1862, including a joint expedition under Lieutenant Rhind with the

USS Crusader in which troops were landed at Simmons Bluff on the Wadmelaw River, where they destroyed a

Confederate encampment.

Despite her successful service, the Planter presentenced a significant problem for the Navy—she burned relatively hard to come-by wood for fuel instead of the abundant coal supplied by the fleet. That fall she was transferred to the Army and

sent for service near Fort Pulaski

on the coast of Georgia. Smalls and his old crew were assigned to

the delivery and then accepted into Army service. He was appointed the regular pilot of the Planter.

On December 1, 1863, the Planter was caught in a crossfire between Union and

Confederate forces. Captain Nickerson ordered Small to surrender. He flatly refused recognizing that he and

the crew would not be treated as prisoners

of war but would be summarily

executed. Smalls asserted command

and piloted the ship out of range of the

Confederate guns.

This

act might have been regarded as a mutiny

and resulted in his death by hanging. But Smalls luck had not run out. His

superiors recognized his bravery and the cowardice of Captain Nickerson. He was appointed

captain of the Planter, becoming the first black man to command a United States ship of war. Smalls continued to serve as captain until

the army sold Planter in 1866 after the end of the war.

The Planter continued in civilian service

for another ten years. Then on March 25,

1876 she ran aground and was damaged trying to save a disabled schooner. The captain beached her to try to repair a staved-in

hull. But a gale blew up and dragged her

back to sea where she foundered. After the crew abandoned ship, she sunk. When informed of her loss, Smalls tearfully

said that it was “like losing a member

of my own family.”

Three yearx

ago this month the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that they had found the wreckage of the Planter in shallow water off the coast.

As for

Smalls, if he had done nothing else in

his life, he would be noteworthy. But his wartime adventure and service were just

Act I in a remarkable life.

After

the war Smalls returned with his prize money and earnings from his service to

his hometown of Beaufort where he bought

his former master’s house. He lived

there with his wife, children and elderly mother until her death. He later even took in his former master’s infirm widow. He went into business with Richard Howell Gleaves operating a store for Freedmen.

|

| Prosperous businessman, respected South Carolina Republican leader, and four times United States Congressman Robert Smalls. |

Smalls became an early leader of the Republican

Party in Reconstruction Era South

Carolina. He was a delegate

at several Republican National

Conventions and participated in the South

Carolina Republican State Convention.

Smalls served as a member of the

South Carolina House of Representatives from 1865 and 1870 and the state Senate between 1871 and 1874. He

even served briefly as the Commander of

the South Carolina Militia with the rank

of Major General.

In

1874, Smalls was elected to the United States House of Representatives,

where he served from 1875 to 1879. From 1882 to 1883 he represented the 5th Congressional District in the House and

the 7th District and served from

1884 to 1887. That was four terms in

Congress, the last two after the withdrawal

of Union troops from the South and the rise of Jim Crowe.

He was

targeted by Democrats for retribution and charged and indicted on phony corruption charges in the letting of a government printing contract. It took a high level deal swapping Democrats

charged with election fraud and intimidation to keep Smalls out of prison.

He was

one of the last Southern Blacks to serve

in Congress and his four terms made him the longest serving Black Congressman until Adam Clayton Powell.

|

| Smalls in his elder years at a Republican Party event. |

After

leaving Congress he was appointed U.S.

Collector of Customs in Beaufort, serving from 1889 to 1911 except for the four years of Democrat Grover Cleveland’s second term.

Smalls

died on February 23, 1915 at the age of 75 and was buried in his family plot in the churchyard of the Tabernacle

Baptist Church in downtown Beaufort.

No comments:

Post a Comment