Old

habits die hard. Like browsing through the daily almanac feature on Wikipedia

for blog post inspiration. I

was reminded that on April 28, 1789 crew

members on the HMS Bounty under the leadership

Fletcher Christian, a young

gentleman serving as an unpaid

volunteer with the functional status

of a warrant officer and mate, mutinied against their captain, Royal Navy Lt. William Bligh. Bligh,

an officer who had sailed under James

Cook and was already a veteran captain of tropical voyages to the Caribbean

and South Seas, and several loyal crewmen we set adrift with scant

supplies in an open launch. The mutiny and its aftermath would become one of the great sea yarns of all time.

What

has this to do with poetry? say you.

Plenty, says I. It inspired verse almost from the

beginning, including an effort by Bligh himself in one of his several literary attempts to clear his reputation. In 1823 no less a figure than George Gordon, Lord Byron himself

published a fictionalized and highly romanticized account in a mini-epic poem The Island. Since that

time the story and it characters have inspired dozens of renderings by bards, balladeers, and poets down to contemporary hip-hop rappers.

The

Bounty, a small three masted, square rigged former

collier—a veritable lumbering tub—had been purchased by the

Royal Navy especially for an unusual mission—to bring a cargo of breadfruit trees

from Tahiti to the West Indies where they were hoped to

become a cheap source of food for slaves on sugar plantations. Mature breadfruit trees produced scores of

large, pulpy and starchy fruit yearly with very little

care required in moist tropical climates. They were a staple of the Polynesian

diet and had been spread by those far

ranging people across the South

Pacific.

An

Admiralty temporarily between wars with plenty of experienced officers and crews available could engage in such economic missions. Bligh, then 43, was recalled to active duty

with the Royal Navy after a few years as a commercial

master in the Caribbean trade, in

1787 especially for this mission.

Earlier, he had been sailing

master on Captain James Cook’s third and final voyage of exploration in the

South Seas. When Cook was killed, Bligh

returned home to England in command of his ship, the HMS Resolution and made

his final report to the Admiralty. No

one in the service was a better fit for the mission.

| Lt. William Bligh from the frontpiece of his own account of the mutiny and his open boat voyage to safety. |

Bligh

handpicked many of the crew,

including former shipmates from the Resolution.

He also added a young gentleman, Fletcher Christian with whom he had made three voyages in the

Caribbean. Bligh had taken to Christian

and the two had developed a master/apprentice relationship. They younger man aspired to a Royal Navy

career and studied navigation under

Bligh. He did not have the family connections or the money to buy an appointment as a midshipman,

so Fletcher, like a few others came aboard as civilian volunteers. Some were listed and paid as able bodied seamen. On board, however, they were treated as

regular midshipmen and junior officers.

Christian rose during the voyage to become virtual First Mate, although the once close relationship between the two

men soured.

The

rest of the crew was typical of the Royal Navy at the time. There were a handful of old salts but much of the crew was made up of hapless young men

swept up by Navy press gangs in England, shanghaied while drunk or drugged—virtually kidnapped. Such men on voyages that could last years

were always a ticking time bomb. The notoriously

harsh discipline of the Royal Navy, including floggings to the edge of

death—and sometimes beyond—for even trifling

offences, was considered necessary

to keep crews under control.

Bligh,

although a strict commander with a quick temper, was not considered a

particularly brutal officer. In fact log

books show that he employed the lash far less frequently than almost any other

commander in the service. Later, one of

the few complaints of his conduct as captain of the Bounty by his brother

officers was that the eventual mutiny would never have occurred if he

had “earned the respect and fear of the

men” by more frequent floggings. He

could, however, lash men with vicious

tongue, dishing out humiliations

that seemed worse than physical

injury. As their relationship

deteriorated on the long voyage, Christian often felt that wrath and scorn.

The

voyage to Tahiti took a full year from October 1787 to October 1788. Bligh’s rigorous demand for hygiene, strict

attention to a healthy diet for

the crew, a three watch system that

left the crew better rested than the Royal Navy’s usual four watches with

officers and crews going on and off duty every four hours, and restrained physical punishment resulted

in an exceptionally fit crew and

good moral. Contrary winds prevented Bligh from

following Cook’s route around Cape Horn so

the ship had to cross the South Atlantic to pass the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian

Ocean. There were layovers for provisions and repairs

at False Bay east of the Cape and at

Adventure Bay on Tasmania.

At

Tahiti Bligh established friendly relations with the local chief, who

remembered him being with Cook 15 years earlier. After gifts

of assorted trade goods, Bligh

asked only for young breadfruit trees, which grew with abundance on the

island. For the Tahitians it was like

trading away sand. Christian was put in

charge of a shore party and established a camp near the main village. For more than five months work went into to

gathering, potting, and loading on board more than 1000 young trees. Much of that work was done by the

natives.

Meanwhile

both those living ashore and those birthing on board had plenty of leisure

time. Almost everyone spent it with the

women, whose culture was sexually accommodating. Many took multiple partners others settled in

with a single companion. Christian did

both, eventually taking up with Mauatua,

to whom he gave the name Isabella

after a former sweetheart. After a few months, almost all of the

shore party and many on board were diagnosed

and treated for venereal disease, which was rife among the natives. That included Christian.

Bligh,

although he did not participate,

took a tolerant view of the hijinks until it began to take a toll

of work performance. The longer the crew

stayed, the worse it got. As it became

clear that the ship was ready to sail, three men tried to desert in a small boat but

were captured, returned, and

flogged. When the ship finally sailed on

April 4, 1789 moral was low but no

one expected a mutiny.

But

Bligh was now hypercritical of the

performance of his crew and junior officers.

Christian was the target of the most abuse and was driven to consider jumping overboard and committing suicide. Things came

to a head when Bligh accused him

of stealing from his personal stash of coconuts. Christian considered trying to desert on a raft but two of the acting midshipmen

convinced him that the crew would be with him if he stayed with the ship and

seized control.

On

April 29 Christian and part of the crew seized Bligh and bound him in his cabin.

Christian was surprised when less than half of the crew actively

supported him. Although no one

resisted—the small ship did not have a complement

of Royal Marines to protect the

Captain and suppress mutiny—many swore allegiance to Bligh and others tried to

remain neutral. After a period of

confusion, Christian decided to put the Captain and two or three of his

strongest supporter over the side in the ship’s small dory. Other clamored to be

included. Eventually he had to allow the

launch, the largest of the ship’s three boats be used. Bligh was joined by 18 other men. Four men with special skills were kept on

board with a promise to be released in Tahiti.

Other loyalists or neutrals were also onboard since the launch was

dangerously overloaded. Bligh and his

men were given about a week’s worth of

food and water and Bligh was allowed some navigational instruments. As the ship cut the boat loose, four cutlasses were thrown down for

protection against hostile natives should them men reach an island.

Christian

had a reduced compliment of 25 men on board the Bounty, almost half of them not active participants in the

mutiny. With a sense of doom, he set

sail for Tahiti assuming that Bligh and the others, thousands of miles from a

safe port were doomed.

But

Bligh was one of the great navigators in the British Navy and his discipline of

his crew paid off. He strictly rationed

the food and water—enough daily to barely sustain life. Some rainfall was captured and a few fish were landed. He set sail first to the relatively nearby

island of Tofua to lay in more

supplies. The natives there were at

first friendly but quickly became

hostile. Bligh barely got his men

off the island when an attack killed

one man. After that the captain decided

to avoid other inhabited islands until he could reach the nearest European

outpost—Timor in the Dutch East Indies about 3,500 nautical or 4000 statute miles. The boat was

at sea most of the next 45 days at sea.

After crossing thousands of miles of open waters, the boat sailed up the

coast of Australia and the Great

Barrier Reef before finally reach a Dutch outpost at Coupang harbor on the island of Timor on June 14. He had lost only the one man to hostile

action.

But

at Coupang and in the festering Dutch capital of Batavia, several men died of disease—likely malaria and being weakened by

starvation. Bligh and four of his most

loyal crew caught a ship for England to which he finally returned on March 14,

1790. He was hailed as a hero for his

epic journey in the small boat. He was

officially brought to court martial in

October but quickly acquitted by a sympathetic court in October. He was promoted to Captain at last and given command of the HMS Providence with orders to complete his breadfruit. He sailed in August of 1791.

Christian

and the Bounty sailed for Tahiti,

arriving at that island on September 22, 1789.

They found the natives far less welcoming than before and the crew was

badly split between Bligh loyalists, Christian’s supporters, neutrals, and men

who simply wanted to debauch themselves

in Tahiti. 15 men voted to stay on the

island. Christian and 8 followers, and

one loyalist detained for his skill as an armorer,

decided to flee to greater safety.

After inviting several Tahitians, including several women and children

on board for a feast, he quietly cut anchor and sailed away, essentially

kidnapping the Tahitians. They decided

to seek refuge on a remote island south east of Tahiti not on any British

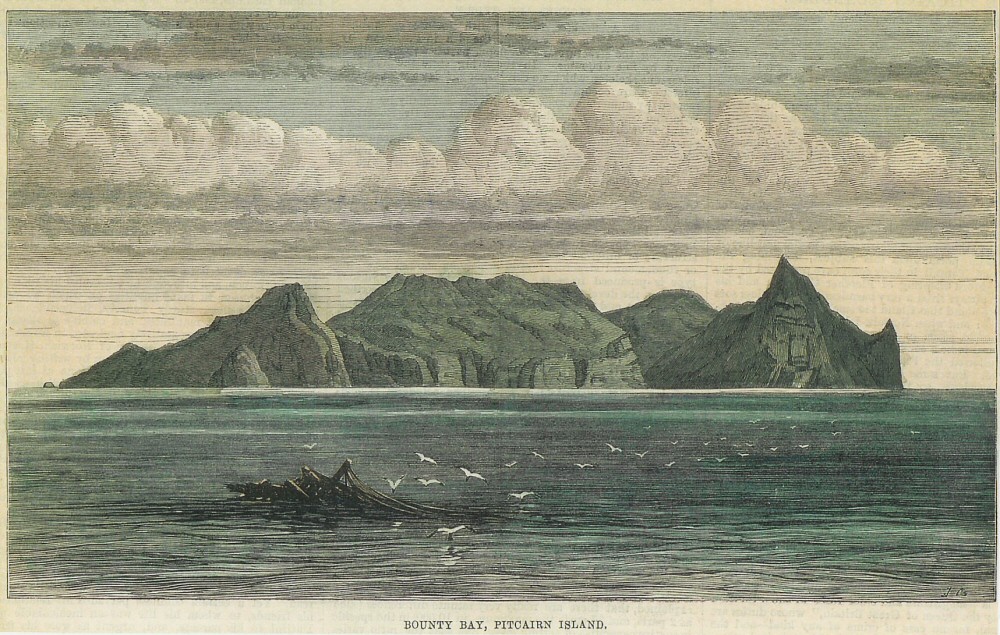

charts. After a long search they found

deserted Pitcairn Island in January

1790. The Bounty was stripped of

everything useful and burned to

prevent its discovery by the Royal Navy.

The mixed group of mutineers and Tahitians settled into an uneasy

community, despite nearly ideal conditions.

Fletcher and Isabella gave birth to a son, Thursday October Christian. Other

children were born. But there were

jealousies over the remaining women and the Tahitian men resented the

mutineers. In September 1793 some of the

Tahitian men made a coordinated attack on the Europeans. Christian and four others were hacked to

death. The four surviving Englishmen

also eventually fell out. One was

murdered by the others.

Eventually

only one mutineer, John Adams,

remained alive. But he was finally able

to bring harmony to the surviving community, taught religion and letters to

the children and built a stable, even thriving community. The Royal Navy finally accidentally discovered

the colony in 1808, deciding to take no action against Adams.

The

men on Tahiti also fared poorly. They

soon divided into two hostile groups, one made up largely of Bligh loyalists

who tried to maintain some discipline and order, and the other of

debauchers. One drunkenly murdered

another who was then killed by the dead man’s Tahitian friends. At least one

“went native” adopting local dress, learning the language and customs, and

getting Polynesian tattoos over much

of his body.

Meanwhile

the Admiralty had dispatched the HMS Pandora,

under Captain Edward Edwards, to

capture the mutineers and return them to England to stand trial. The ship arrived at Tahiti on March 23, 1791, and within a few days all 14

surviving Bounty men had either surrendered or been captured. Edwards made no distinction between loyalists

and mutineers, decided to bring them all back in chains to face court

martial. On the return voyage the Pandora ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef. In the confusion one escaped with other non-Bounty prisoners and four drowned. The remaining men were bound for yet another

long open boat trip to Coupang. They reached England on June 19, 1792 and

faced court martial in September.

Bligh,

who had promised to vouch for the

loyal men, was still absent on the second breadfruit expedition. Testimony included revelations and allegations of

Bligh’s behavior that began to swing public

sentiment against him. Even many

formerly staunchly supportive Navy officers turned. Radical

Whigs now took up the missing Christian as a hero against tyranny and cast the mutineers along the lines of the liberators of the Bastille. Tories

worried that they would become revolutionary

rallying cries.

At

the court martial the testimony of four of the men that they were loyal men

detained by Christian went unchallenged and they were acquitted. Testimony by

survivors of Bligh’s open boat went against the others, two of whom maintained their innocence and offered their voluntary

surrender to the Pandora as evidence of their good intentions. But the court found all of the remaining six men

guilty and sentenced them to hang with

recommendations of mercy for the two men who maintained

their innocence. Those men were

ultimately pardoned by King George

III. One of the men obtained a stay

of execution and ultimately was reprieved

and pardoned. The remaining three, all common seamen with no family connections and who were too poor for legal representation were hung at Portsmouth on October 28, 1792. The Whig press charged that “money had bought

the lives of some, and others fell sacrifice to their poverty.”

Fletcher

Christian’s brother, a prominent jurist, published the proceedings of

the court, much of it critical of Bligh along with an Appendix of other

accounts that tended to vindicate Fletcher and vilify Bligh. Bly responded with his own book, long in

preparation, A Voyage to the South Sea Undertaken by Command of His Majesty: For the

Purpose of Conveying Bread-Fruit Trees to the West Indies. Although the account of his open boat voyage

won back some lost support, Bligh’s reputation was never the same. In the wake of the Court Martial report and Appendix the Admiralty let Bligh sit on the beach without a command.

Eventually

Bligh found enough support to be given a ship.

In the next few years he commanded ever larger and heavier war ships carrying more guns with each new assignment. In 1796

while in command of the 64 gun HMS Defiant his crew joined in the

broad Spithead Mutiny involving 16

ships in protests over the treatment,

pay, and conditions of common seamen.

It was more like an industrial

strike than a traditional mutiny.

The shocked Royal Navy actually met

most demands and promised pardons

to the mutineers.

The

next year Bligh and the Defiant were

at the Nore, an anchorage in

the Thames when another mass mutiny

broke out. This one lacked the unity of

Spithead and many ships and crews slipped away from the mutineers only to be fired upon by them. A blockade

of London was attempted. Demands

were expanded to include an immediate peace

with France—considered proof that the mutineers were republican revolutionaries. Eventually

the mutiny failed when its leader, Richard

Parker hoisted a signal for the mutinous ships to sail for France. This was a step to far toward treason and

most ships refused to sail. The mutiny

was crushed by loyal ships and Parker arrested and hung. 29 others were hanged, 29 were imprisoned,

and 9 flogged, while others were sentenced to transportation to Australia.

In

neither of these mutinies was any action or abuse by Bligh cited as a reason

for the insurrection. He was only peripherally involved at Spithead. At the Nore when he re-gained control of his

ship and crew, he was engaged in action against the mutineer. But his presence at both mutinies re-enforced

the public image of him.

Bligh

did enjoy successes, however. On October

11 the Defiant, back on war sea duty engaged three Dutch ships at the Battle of Camperdown, defeating them, and capturing one prize with

the Dutch admiral on board. In 1801 at the Battle of Copenhagen Bligh and his 56-gun ship of the line HMS Glatton

were specifically cited by Admiral Horatio Nelson for a leading

part in the victory.

| In this pro-rebellion primative painting New South Wales Gov. Bligh is depicted as being arrested by troops while hiding under his bed, something that almost surely did not happen. |

In

1805 Bligh’s reputation as a disciplinarian earned him an extraordinary appointment—Royal

Governor of New South Wales with

an annual income of £2000, a fortune. When Bligh arrived in Sydney his old imperiousness, sharp tongue, demand to instant obedience quickly put him at odds with both influential and wealthy

local planters and the officers off

the New South Wales Corps. When he attempted to suppress a long established but

illegal rum trade by Army officers

and key settlers, the 400 soldiers of the New South Wales Corps under the

command of Major George Johnston

marched on Government House in Sydney and arrested and deposed Bligh. A rebel

government was established. Bligh sailed

on the HMS Porpoise to Hobart in

Tasmania seeking support for move to re-assert control. The authorities there refused to get involved

and Bligh was kept a virtual prisoner on the Porpoise for two years.

Finally,

in January 1810 he got word from

London that the rebellion had been declared illegal and a mutiny. Bligh returned to Sydney to gather

evidence for Johnston’s Court Martial but was never restored to his position. He returned to England aboard the Porpoise with the new rank of Commodore. Although Johnston

was convicted of mutiny, he was only cashiered

from the service and allowed to return to Sydney to resume his lucrative business dealings. The lightness of the sentence was a slap

in the face to Bligh.

He

did get further promotions, first to Rear

Admiral and then to Vice Admiral of

the Blue, but he never again got a significant sea command. His last duties were preparing navigation

charts and making improvements to the sea wall and removal of sand bars in Dublin’s River Liffey—an important but unglamorous assignment.

Bligh

died in London on December 17, 1817 at the age of 63 and he was buried in a

family plot under a monument capped by

a carved breadfruit.

|

| The book that cemented the images of Bligh and Christian. |

A

few years later Lord Byron portrayed him as a not quite irredeemable villain to Fletcher Christian’s dashing hero in his The

Island. Most subsequent accounts

have followed that interpretation. Most

notably Charles Nordhoff’s and James Norman Hall’s 1932 international Best Seller Mutiny

on the Bounty. That became the

first of the Bounty Trilogy which also included Men Against the Sea about

Bligh’s open boat sail to safety and Pitcairn’s Island. The Bounty story had already been filmed in a 1916 silent version and in 1933 an Australian

dram/documentary hybrid starring the very young Errol Flynn as Christian was released.

But

mighty MGM bought the rights to Nordhoff and Hall’s book for

their 1933 classic Mutiny on the Bounty staring Charles Laughton as Bligh, Clark

Gable as Christian, and Franchot Tone

as a midshipman and Christian’s best friend. Laughton’s Bligh was a memorable ogre and Gable always a hero. In 1962 the studio revisited the Bounty in a Super Panavision wide screen epic famously starring Marlon Brando as Christian and Trevor Howard as Bligh. It is best remembered for behind the scenes as Brando hijacked

the production, ran up production costs astronomically,

and went native involving himself

with and eventually marrying his Tahitian

leading lady. The film was a critical and box office flop

which nearly killed the most prestigious

studio in Hollywood history.

| Even today, for most of us Clark Gable and Charles Laughton are Fetcher Christian and William Bligh. |

In

1982 a version of the story not based on Nordhoff and Hall’s book was brought

to the screen after nearly a decade in

development by director David Lean. The

Bounty instead was based on the revisionist

Captain Bligh and Mr. Christian by

Richard Hough which took a much more

sympathetic view of Bligh without excusing him his faults. It was originally intended to be made into

two films, one covering the voyage of the Bounty,

Tahitian layover, mutiny, and Christian’s attempt to find safety for his

followers and the other on Bligh’s open boat sail. Lean wanted completely historically accurate

film and had a full scale replica of the Bounty constructed even before the script was completed. Warner

Bros., fearing a money-pit disaster like MGM’s second effort, withdrew funding for the film forcing

Lean to jam two films into one. A search

for a new backer ended with Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis,

who was best known for big, splashy

films. During pre-production the

original screen writer, Robert Bolt suffered

a stroke and was unable to finish the script,

which was finished by journeyman

writer and BBC presenter Melvyn

Bragg.

Lean

completed the casting including Anthony

Hopkins as Bligh, and rising Australian star Mel Gibson as

Christian. Conflicts with De Laurentiis caused

Lean, the most acclaimed British

director of his generation, to drop out.

Gibson had enough clout with

the producer to bring on his friend Roger Donaldson who had no experience

on such an epic film. The production shot on location in Australia,

Tahiti, and London was plagued with production problems, especially un-cooperative weather. But somewhat amazingly, it came in under budget.

The

film opened to wildly mixed reviews. Some praised it for its accuracy and for

showing how the Tahitian, far from living as idealic children of nature were exploited and abused by

the Bounty crew and mutineers. They also appreciated showing that Bligh and

Christians were friends and started out with an almost father/son relationship that some though had homoerotic undertones. Other

critics found the script a mess and felt that Gibson lacked the charisma of Gable and Brando. Gibson thought the film was a failure

because it was not revisionist enough.

It still tried to cling to Christian as a hero and Bligh as a villain,

at least until he redeems himself in

the open boat.

In the old

version, Captain Bligh was the bad guy and Fletcher Christian was the good guy.

But really Fletcher Christian was a social climber and an opportunist. They

should have made him the bad guy, which indeed he was. He ended up setting all

these people adrift to die, without any real justification. Maybe he’d gone

island crazy. They should have painted it that way. But they wanted to

exonerate Captain Bligh while still having the dynamic where the guy was

mutinying for the good of the crew. It didn’t quite work.

The film had

some success at European film festivals and

did moderately well at the box office but

was not the blockbuster that De

Laurentiis counted on.

And, as Gibson

predicted, it was not enough to rescue Bligh from the image of a tyrant still

etched in the public mind by the powerful performance of Charles Laughton all

those years before.

Here are two of

the early poems—Bligh’s apologia and Byron’s Romance—that fixed the story in

the public mind.

Captain’s Log -

22.23

27th

April 1789 –

How subtle did

the harmony of quill,

against this

parchment drenched of one disdain,

afford to not

subside or whether still,

the crew as one,

a nightfall weather vain.

A time when

fluid ounce became a quart,

if asked if fury

raged when keenest sought,

the splendour

being close to chivalry,

forgets the

golden rule, “no rivalry” ...

What melody is

this when moonlight mesh,

compares with

fragrance from the one besides,

inventiveness to

steer their wanton fresh

Tahiti's beauty

more than makes resides,

enough of this

abatement to prowess,

that goods and

things like this are duly kept,

but women? Oh,

but no I say, have leapt.

Endearing as

they are, my eyes have closed,

enough to see

for sorrow, their desire,

what innocense

there was have I disclosed

the passion of

the crew is close to fire!

Delirious a

thought attaches stealth,

as mighty as

those cargoes found elope,

maintain to

course the survey as we’d hope

would honey

sweet the rage review one’s wealth?

Capstan to the

turn of wind behind,

sets sail

amongst what rapture petals do

those women with

their anthers in pursue,

of frolic did

intentions seek their kind?

Incredible if

blameless few could stay,

delicious even -

thinking I, as them

could entertain

good fortune with dismay

returning

without slender to condemn.

(hesitates)

... look back as often will a candid pry,

if all let loose

on board the Bounty, high

from issues due

to those left fresh deny,

with delicate

annoyance. ~ Captain Bligh.

—William

Bligh

The Island

Canto

I

I.

The morning

watch was come; the vessel lay

Her course, and

gently made her liquid way;

The cloven

billow flashed from off her prow

In furrows

formed by that majestic plough;

The waters with

their world were all before;

Behind, the

South Sea's many an islet shore.

The quiet night,

now dappling, ‘gan to wane,

Dividing

darkness from the dawning main;

The dolphins,

not unconscious of the day,

Swam high, as

eager of the coming ray;

The stars from

broader beams began to creep,

And lift their

shining eyelids from the deep;

The sail resumed

its lately shadowed white,

And the wind

fluttered with a freshening flight;

The purpling

Ocean owns the coming Sun,

But ere he

break- a deed is to be done.

II.

The gallant

Chief within his cabin slept,

Secure in those

by whom the watch was kept:

His dreams were

of Old England’s welcome shore,

Of toils

rewarded, and of dangers o'er;

His name was

added to the glorious roll

Of those who

search the storm-surrounded Pole.

The worst was

over, and the rest seemed sure,

And why should

not his slumber be secure?

Alas! his deck

was trod by unwilling feet,

And wilder hands

would hold the vessel’s sheet;

Young hearts,

which languished for some sunny isle,

Where summer

years and summer women smile;

Men without country,

who, too long estranged,

Had found no

native home, or found it changed,

And, half

uncivilised, preferred the cave

Of some soft

savage to the uncertain wave-

The gushing

fruits that nature gave untilled;

The wood without

a path- but where they willed;

The field o’er

which promiscuous Plenty poured

Her horn; the

equal land without a lord;

The wish- which

ages have not yet subdued

In man- to have

no master save his mood

The earth, whose

mine was on its face, unsold,

The glowing sun

and produce all its gold;

The Freedom

which can call each grot a home;

The general

garden, where all steps may roam,

Where Nature

owns a nation as her child,

Exulting in the

enjoyment of the wild

Their shells,

their fruits, the only wealth they know,

Their

unexploring navy, the canoe

Their sport, the

dashing breakers and the chase;

Their strangest

sight, an European face

Such was the

country which these strangers yearned

To see again- a

sight they dearly earned.

III.

Awake, bold

Bligh! the foe is at the gate!

Awake! awake!-

Alas! it is too late!

Fiercely beside

thy cot the mutineer

Stands, and

proclaims the reign of rage and fear.

Thy limbs are

bound, the bayonet at thy breast;

The hands, which

trembled at thy voice, arrest;

Dragged o'er the

deck, no more at thy command

The obedient

helm shall veer, the sail expand;

That savage

Spirit, which would lull by wrath

Its desperate

escape from Duty’s path,

Glares round

thee, in the scarce believing eyes

Of those who

fear the Chief they sacrifice:

For ne’er can

Man his conscience all assuage,

Unless he drain

the wine of Passion- Rage.

IV.

In vain, not

silenced by the eye of Death,

Thou call’st the

loyal with thy menaced breath

They come not;

they are few, and, overawed,

Must acquiesce,

while sterner hearts applaud.

In vain thou

dost demand the cause: a curse

Is all the

answer, with the threat of worse.

Full in thine

eyes is waved the glittering blade,

Close to thy

throat the pointed bayonet laid.

The levelled

muskets circle round thy breast

In hands as

steeled to do the deadly rest.

Thou dar’st them

to their worst, exclaiming- “Fire!”

But they who

pitied not could yet admire;

Some lurking

remnant of their former awe

Restrained them

longer than their broken law;

They would not

dip their souls at once in blood,

But left thee to

the mercies of the flood.

V.

“Hoist out the

boat!” was now the leader’s cry;

And who dare

answer “No!” to Mutiny,

In the first

dawning of the drunken hour,

The Saturnalia

of unhoped-for power?

The boat is

lowered with all the haste of hate,

With its slight

plank between thee and thy fate;

Her only cargo

such a scant supply

As promises the

death their hands deny;

And just enough

of water and of bread

To keep, some

days, the dying from the dead:

Some cordage,

canvass, sails, and lines, and twine,

But treasures

all to hermits of the brine,

Were added

after, to the earnest prayer

Of those who saw

no hope, save sea and air;

And last, that

trembling vassal of the Pole-

The feeling

compass- Navigation’s soul.

VI.

And now the

self-elected Chief finds time

To stun the

first sensation of his crime,

And raise it in

his followers- “Ho! the bowl!”

Lest passion

should return to reason’s shoal.

“Brandy for

heroes!” Burke could once exclaim-

No doubt a

liquid path to Epic fame;

And such the

new-born heroes found it here,

And drained the

draught with an applauding cheer,

“Huzza! for

Otaheite!” was the cry.

How strange such

shouts from sons of Mutiny!

The gentle

island, and the genial soil,

The friendly

hearts, the feasts without a toil,

The courteous

manners but from nature caught,

The wealth

unhoarded, and the love unbought; sic

Could these have

charms for rudest sea-boys, driven

Before the mast

by every wind of heaven?

And now, even

now prepared with others' woes

To earn mild

Virtue’s vain desire, repose?

Alas! such is

our nature! all but aim

At the same end

by pathways not the same;

Our means- our

birth- our nation, and our name,

Our fortune-

temper- even our outward frame,

Are far more

potent o’er our yielding clay

Than aught we

know beyond our little day.

Yet still there

whispers the small voice within,

Heard through

Gain’s silence, and o’er Glory's din:

Whatever creed

be taught, or land be trod,

Man’s conscience

is the Oracle of God.

—George

Gordon, Lord Byron

This is a great blog on an eternal story. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteI came here on reading Fitzsimon’s “Mutiny on the Bounty” where he states that the story inspired poems from Bligh and Byron, yes, but also from Wordsworth (a younger schoolmate of Christian), Coleridge (with Christian as the Ancient Mariner) and later, Tennyson. That’s quite a story.

A couple of notes - morale, but perhaps the mutiny also arose through low moral. The feature over Bligh’s tomb is apparently not a breadfruit but a lumpy representation of an eternal flame.