Note—Second of a holiday two-fer for New Year’s Eve

Although there have occasionally been other songs that made feeble attempts to displace it, New Year’s Eve belongs firmly to Auld Lang Syne and it promises to remain supreme in defiance of any and all changes in musical tastes and styles.

Most of us know that the song comes from a poem by the revered Ploughman Poet and Scottish national icon Robert Burns. But you may not know the whole story.

The Scottish Ploughman Poet Robert Burns.

After his first blush of fame with the publication of his Kilarnock Poems in 1786, Burns began his fruitful relationship with the editor and publisher James Johnson who was preparing to publish his Scots Musical Museum. He collected and often rewrote scores the songs of this great collection, which preserved traditional Scottish music when it could have easily vanished. One of the songs he sent was Auld Lang Syne with the notation “The following song, an old song, of the olden times, and which has never been in print, nor even in manuscript until I took it down from an old man.”

That was not quite true on a couple of accounts. Other collectors had recorded variants and in 1711 James Watson published a version that showed considerable similarity in the first verse and the chorus to Burns’ later poem and is almost certainly derived from the same old song. Burns changed it from a romantic song about old lovers to a nostalgic drinking song of old friends. Most of the words in Scotts we now sing were written by Burns.

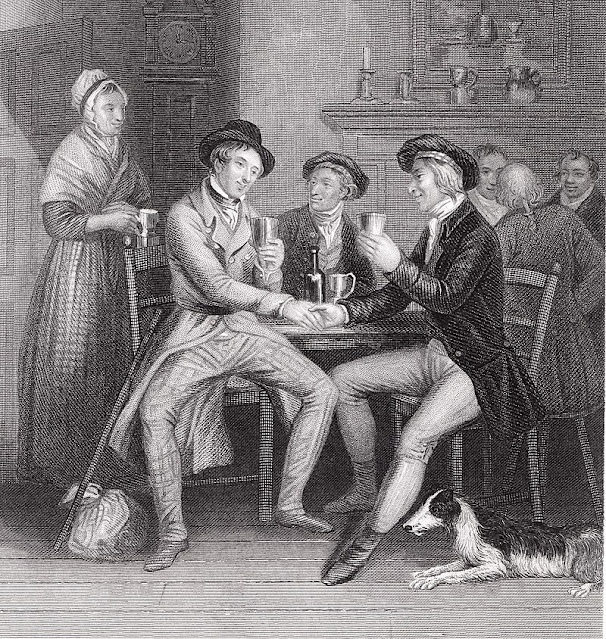

John Masey Wright's and John Rogers' illustration of Auld Lang Syne in 1841.

After his early death in 1796 at the age of only 37, the song took on a special significance as a legacy of the beloved poet.

The melody we now sing may or may not have been the one that Burns originally heard but became standard in the early years of the 19th Century. It is pentatonic—based on a five note scale—Scots folk melody, originally a sprightly dance in a much quicker tempo.

Exactly when the song became associated with New Year’s is unknown. It is possible the earlier folk versions were already sung at that time. But was incorporated in Hogmanay—the last day of the old year and the first of the new—celebrations by the mid-19th Century.

Nobody in the world celebrates New Years with zest and ritual like the Scots. You can thank those dour old Calvinists of the National Kirk of Scotland—the Presbyterians—for more completely scouring Christmas from the calendar than Oliver Cromwell and his Puritans ever dreamed in England. If Scottish Catholics kept Christmas in their hearts, the kept their mouths shut about it and the practice faded even in their communities. After the celebration of Christmas was no longer outright banned it was still shunned as being “too English” and did not become a legal holiday in Scotland until 1958 and only then because so many English were moving into the border areas and were employed at firms in the big cities.

The Hogmanay circle singing of Auld Lang Syne at the stroke of midnight.

Hogmanay has many quaint customs, but they center on the stroke of midnight. Then the central room of a home hosting the celebration was cleared of furniture and guests joined hands with the person next to them to form a great circle around the dance floor. At the beginning of the last verse, everyone crosses their arms across their breast, so that the right hand reaches out to the neighbor on the left and vice versa. When the tune ends, everyone rushes to the middle, while still holding hands. When the circle is re-established, everyone turns under their arms to end up facing outwards with hands still joined.

The song spread rapidly around the globe thanks to the Scottish diaspora to British Empire nations—especially Canada—and to the United States. Scottish regiments spread the song even wider and it was adapted for use by British troops generally from India to Africa, to the Middle East.

It wasn’t until the 1890’s, however, that there was printed mention of the song being used publicly at New Year’s in the United States, although it undoubtedly was sung in Scottish communities. When the first illuminated ball was dropped in New York City’s Times Square in 1907 the song was so firmly identified with New Year’s that the crowd sang it after the ball touched down.

Guy Lombardo leading His Royal Canadians during a New Year's Eve broadcast in the 1960s.

But Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians really cemented Auld Lang Syne as the New Year’s Eve song. Lombardo first broadcast a New Year’s Eve program on CBS Radio on December 31, 1928. He continued broadcasting from the Roosevelt Room until 1959, and then moved his base to the larger Waldorf Astoria. In 1959 the New Year’s Eve program was first aired on CBS Television and continued on that network for 21 years. After Lombardo’s death the song was still played in all of the airings of the Times Square celebrations.

The Pipers lead the Band of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards on parade in Edinburgh.

Today we fittingly turn to an instrumental version by the Band of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. Regimental musicians like these helped spread Auld Lang Syne across the British Empire and English speaking world.