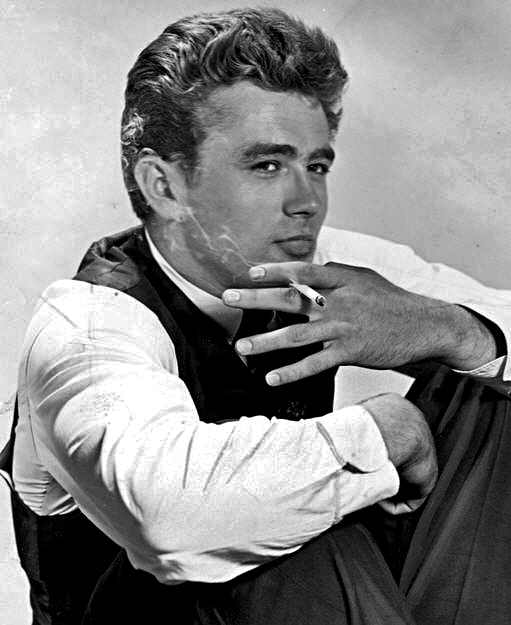

It has been 67 years since James Dean died

in a wreck of his sports car on a country

highway near Cholame, California on September 30, 1955.

He was just 24 years old. At the time of his death, he had shot to fame on the strength of one already released film—East of

Eden—and had two more completed

projects in the can, including

the role that would define a generation. On

this slender body of

work rests the fame that has eclipsed most of his contemporaries and endured as a legend.

Today he is a cultural icon that

remains undiminished by

time. Generations of adolescents, whether they know it or

not, do what John Mellencamp described in The Ballad of Jack and Diane, “Scratches

his head and does his best James Dean.”

Dean was born on February 8, 1931in Marion Indiana.

His father was a failed farmer who took up a trade as a dental assistant. The family moved to Santa Monica, California

when he was young. He had a difficult

relationship with his father but was extremely close to his mother. When his mother died when

Dean was 9, he was sent back to Indiana to live in the Quaker home his paternal aunt and uncle in Fairmount.

An unhappy and moody child, he sought council

from a local Methodist minister,

Rev. James DeWeerd, who became a mentor

and substitute father figure.

DeWeerd introduced young Dean to many things beyond their small community

including theater, auto racing, and bullfighting. Some biographers

suggest that this relationship may

eventually have become sexual.

I come upon it suddenly, alone–

A little pathway winding in the weeds

That fringe the roadside; and with dreams my own,

I wander as it leads.

Full wistfully along the slender way,

Through summer tan of freckled shade and shine,

I take the path that leads me as it may–

Its every choice is mine…

Despite

being an indifferent student, Dean

was popular in the local high school and was both an athlete and a participant in drama and forensic competitions. After graduating in 1949 he moved back to

California where he lived with his father and stepmother while attending Santa Monica College with a

declared pre-law major.

He did not last long before transferring to the University of Southern

California (UCLA) where he switched to a drama major, rupturing

his tenuous relationship with his

father.

His talent and ability did not go unnoticed. He quickly earned the coveted

role of Malcolm in a production of Macbeth. He also enrolled in James Whitmore’s

acting studio. In January 1951 Dean dropped out of school to

pursue acting as a career.

He

found it difficult. After a

promising start with a role as the Apostle John in an Easter religious television broadcast, he managed to get just three

walk-ons, unaccredited movie jobs. Dean was parking cars for a living at CBS Studios and virtually homeless when he was noticed

by Rogers Brackett, a radio

director for an advertising agency.

Brackett took him in and mentored his career. Both Brackett and Whitmore

encouraged the young actor to go to New York for stage experience and training.

In the big city, Dean’s career went on the upswing. He made some money testing stunts for the quirky game show Beat the Clock

and was soon getting speaking roles

on various CBS dramatic anthology

series then being presented live

from New York. He followed

in the footsteps of his acting idol Marlin

Brando by gaining admittance to the prestigious Actors Studio

where he studied the Method under legendary teacher Lee Strasberg.

There

were even better roles on Golden Age of Television programs like Studio

One, Lux Video Theater, Kraft Television Theatre,

Hallmark Hall of Fame, You Are There, and Omnibus.

He also found work in ambitious avant-garde

off-Broadway theater productions

including a stage version of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis

and a translation of the Greek tragedy Women of Trachis by poet Ezra Pound.

It was

a well reviewed turn on Broadway in

a production of André Gide’s The Imortalist in 1954 that

attracted the attention of Hollywood. At the suggestion of screenwriter Paul Osborn and over the initial objection of the

studio, director Elia Kazan bypassed his close associate Brando to cast Dean

as Cal in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden.

Dean stunned the director and fellow cast members including Jo

Van Fleet, Raymond Massy, and fellow Actors Studio alum Julie

Harris by improvising key bits of business in the

film. The film opened to strong reviews and brisk ticket sales despite the unknown Dean in the lead. The

film went on to win numerous awards

including Best Drama at Cannes and a Golden Globe.

Dean would win a posthumous Academy Award for his role.

On the

strength of reports from the set of East of Eden Warner Bros.

decided to revive a long abandoned project—Rebel Without a Cause

based solely on the title of psychiatrist Robert M. Lindner’s

1944 non-fiction book on criminal pathology. Director Nicholas Ray helped

develop the story of suburban teenage

angst and rebellion. Dean

led the cast as Jim as the troubled lead with Sal Mineo and Natalie

Wood as the outcast members of

his surrogate family.

Dean

was drinking heavily during the

filming and was quickly getting a reputation

for being wild. His fondness

for fast cars and racing enhanced his bad

boy image. He began road racing

sports cars in early 1955 and placed in the top four at several meets. Forbidden to race while

working on his next film, Dean upgraded to a limited edition Porsche 550 Spyder which he had customized and nicknamed The

Little Bastard.

The

next film was Giant an epic, somewhat overwrought multi-generational depiction of a Texas cattle and oil baron’s family based on the book by Edna

Ferber. Dean purposefully chose to play a supporting role to leads Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson

because he wanted to break away from being type cast as sensitive, alienated young

men. Instead, he played Jett Rink, an ignorant hired hand jealous

of Hudson’s wealth and beautiful wife who goes on to become a

successful oil wildcatter and ages into a still resentful, drunken tycoon.

But Dean played the older character as so extravagantly

deranged that it is impossible to believe that he could have won the affections of his

old rival’s daughter. But in Cinemascope

grandeur with three box office

stars, the film was destined to be a hit.

With Giant

going into postproduction, Dean filmed a public service announcement in his Jett Rink cowboy costume advising teenager to drive safely and obey the

speed limit.

On

September 23, Dean proudly showed off The Little Bastard, now decorated with the racing number 130 on the hood, sides, and back to British actor Alec

Guinness who thought it looked sinister,

“If you get in this car,” he told Dean, “You will be dead in a week.”

Exactly seven days

later, on September 30 Dean and his mechanic Rolf Wütherich set

off from Competition Motors, where the Porsche had been readied for on

their way to a race at Salinas. Originally he had planned to trailer the car to the race but decided

that he needed more time behind the wheel to get the feel of the new

car. A crew member and a photographer accompanied the car in

Dean’s station wagon still equipped

with a trailer. Near Mettler Station in Kern County Dean

was ticketed for driving ten miles

an hour over the 55 m.p.h. speed limit.

After that the vehicles became separated.

A few minutes after refueling Dean was headed west on what was then U.S. 45 near

Cholame when a five year old Ford

coupe driven by a 23 year old college student headed in the opposite

direction changed lanes to take a fork in the road and

drove into Dean’s lane. “That guy’s gotta stop,” he told Wütherich,

“He’ll see us.” Seconds later the cars collided nearly head on.

The coupe’s front

grill, riding over the low hood

of the sports car stuck Dean in the head.

He suffered a fractured skull and jaw, a broken neck, and massive

internal injuries. Although still barely breathing when an ambulance

arrived, he died on the way to the hospital.

Wütherich was thrown clear of the car and survived.

The driver of the other vehicle, who claimed never to have seen Dean, suffered minor head injuries and was released un-charged. Despite legends to the contrary, physical evidence showed that Dean was not speeding at the time of the crash.

Dean was buried

by his family at Park Cemetery in Fairmount. Reaction to his death by the public was

sharp and instantaneous.

Like John Dillinger had once recommended, he had “lived hard, died

young, and left a good looking corpse.”

Rebel Without a Cause was released on

October 27. The image of Dean as the rebellious teenager instantly became

inseparable from the actor’s real identity.

Giant was delayed in getting to the screen

by Dean’s death. Some of his dialoged

in his climatic drunken scene was inaudible. Actor Nick Adams had

to be brought in to dub

sections. Other long shots had

to be made with doubles. Still, when that film was released in November

of 1956 it became the biggest grossing

film in Warner’s history and remained so until Superman

twenty-two years later.

Since his death Dean has been the inspiration for imitative performances by generations

of actors, several songs, novels, and even a French language musical. All three of his films are

considered classics and are usually included in round-up of the greatest

American films.

But perhaps nothing says more about Dean’s iconic status more than the 1984 painting by Gottfried Helnwein inspired

by Edward Hopper’s Nightscape. Reproduced as a popular

poster, Helnwein placed a lone James Dean at the front of dark dinner while Marilyn Monroe and

Humphrey Bogart shared a coffee and Elvis Presley cleaned up behind the counter.

.jpg)

.jpg)