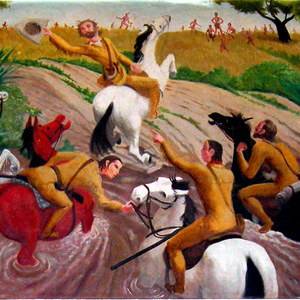

| The Battle of Blue Lick as depicted in a display by the Kentucky National Guard, the descendant of the routed Militia. |

School children in those quaint days when they were supposed to memorize important events and dates in history, could tell you with

certainty that the American Revolution was

won on October 19, 1781 when Lord Charles

Cornwallis surrendered his army to George

Washington’s Continental Army and a large French force.

Certainly with the main British Army in the

bag as prisoners of war, it effectively put an end to most fighting

in the settled eastern coastal regions.

General Washington took the Continental Army into camp at Newport. By tacit gentlemen’s agreement garrisons left isolated were

allowed to remain un-molested in barracks until they could be

withdrawn. Some quickly were evacuated

to Nova Scotia, other lingered for months stretching into years. Occasionally some patrol would clash

with local militia and some local historians have elevated a few almost

bloodless skirmishes here and there to the status of “last battle of the

Revolution.” Maybe a dozen towns fight

like dogs over an already stripped bone for the title.

The war officially dragged on until September 3,

1783 when Benjamin Franklin and John Adams secured British agreement to

the Treaty of Paris ending

hostilities.

But

in frontier regions west of the Alleganies, it was a whole different story. The battle for the control of the heart of the continent continued with a particularly savage intensity on all

sides.

| Col. George Rogers Clark as a Western Commander. |

Although

Colonel George Rogers Clark had

weakened the British in the west by his legendary captures of Forts Kaskaskia in 1778 and Vincennes in

1779, they still held the critical stronghold of Fort Detroit, through which they waged a largely proxy war on the scattered frontier settlements in the Ohio Valley and as far south as modern Tennessee and North Carolina. They armed

and advised a coalition of western tribes incensed by

the settlers seizing some of their richest traditional hunting grounds.

Tribes

including the Shawnee, Lenape (Delaware), Mingo, Wyandot, Miami, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Potawatomi, were armed with British

muskets and villages were supplied provisions to allow warriors to abandon the hunt and harvest

for extended campaigns against the

scattered settlements, particularly those in Kentucky, then a western

county of Virginia. Sometimes they were accompanied by British officers and small contingents of troops, occasionally even deploying a light field cannon.

Warriors were rewarded with bounty

payments on settler scalps regardless of age or sex—which spread that once

localized custom to Native American tribes

all over the continent.

The

British regarded the tribes as allies

and the warriors as irregular

troops. Horrified settlers who found

their farms raided, families slain, and small villages wiped out, regarded them as blood thirsty savages. And they vowed

revenge.

The

war had settled into a familiar pattern.

The British would arrange a raid

across the Ohio into Kentucky with large forces of their irregulars. Among the settlers the tell tale sign of smoke from the burning cabins of neighbors would be a signal to retreat into well fortified block houses

or palisaded forts which they could

usually defend with accurate rifle fire. Traditionally, native warriors would abandon an attack after a day or so,

but their British advisors taught them the European

art of the siege. Although the posts

could usually hold out, some were overtaken and the inhabitants generally slaughtered or women and children taken as captives. Others endured long sieges until the Indians,

becoming bored, would drift away no matter what their British

officers could do.

Local militia would respond

from surrounding areas to try to

relieve the sieges. Frequently they

would mount their own expeditions

into Indian territory usually fruitlessly

chasing the warriors and burning

abandoned villages.

George

Rogers Clark was in over-all command of the Kentucky militia and was the one

commander that both the British and Indians feared and respected. But he

could not be everywhere and his militia spent

most of their time on their own farms awaiting muster orders.

| Tory Simon Girty was feared and despised on the frontier. |

In

1792 50 British Rangers under Captain William Caldwell gathered 1,100 warriors supervised by Pennsylvania Tories Alexander McKee, Simon Girty, and Matthew

Elliott to attack Wheeling, on

the upper Ohio River probably the largest

force sent against American settlements.

But

the native irregulars got wind of rumors

that Clark was preparing to cross the river further west and attack their

villages with a large force. This was a

rumor undoubtedly spread by agents

of the wily Clark, who made a demonstration

of patrolling the river in a large keelboat armed with small swivel cannon. Most of Caldwell’s auxiliaries melted away to defend their homes and

the attack on Wheeling had to be abandoned.

Clark

never intended to mount an invasion of the Indian homeland. He was spread

too thin and feared that if he mustered a large enough force, it would leave his settlements unprotected from

attacks.

Frustrated,

Caldwell and less than 300 of his remaining warriors crossed the Ohio to attack

Bryan Station at today’s Lexington.

Most of the settlers in the area were able to retreat to the

fortified station, where they watched helplessly as their crops and cabins were

burned. The fort was besieged for two

days starting on August 15. But scouts

reported that contingents of militia were nearing and engagement was broken

off. Caldwell and his force slipped away,

heading for the villages deep within the heavily

wooded interior.

About

185 militia from Fayette and Lincoln Counties under the command of

senior militia Colonel John Todd with

Lt. Col. Daniel Boone and Steven Trigg as his subordinates relieved the fort on August 18.

A second column of Lincoln militia was expected but had not arrived.

At

a hastily convened council of war, experienced Indian fighters recommended

against immediate pursuit of Caldwell, who by this time had a 40 mile lead. But Todd, the kind of reckless hot head who would make repeated appearances in frontier history with uniformly tragic results, mocked the cautious officers as cowards.

Unable to resist a challenge to their honor, the majority

of officers who had advised caution fell

into line. By afternoon they were mounted up and pursuing a broad and easily

followed trail. They made camp that night and then reached

the Licking River near Lower Blue Licks, a natural spring and salt lick, the next

morning, August 19.

Native

scouts could be observed on the top of a

hill across the river. A large open area led up to the top with scrub wood on either side. Another council was called and Todd asked

Boone, his most experienced officer

and universally respected, his

opinion. Boone told him that the trail

had been too easy to follow, that

ordinarily the little army would have never

caught glimpse of any scouts. He was

sure that they were being lured into an

ambush. Even Todd agreed and it

looked like the force would stay put, at least until the rest of the Lincoln

militia could come up.

|

| A WPA Post Office mural at Flemingsburg, Kentucky depicts Major McGary's disastrous charge across the creek into the British and native trap. |

But

Major Hugh McGary, who had been particularly stung by Todd’s taunts the

day before, hopped on his horse and in a display

of bravado yelled out, “Them that ain’t cowards, follow me!” The men, thinking the order had been given,

followed as McGary forded the river. The other reluctant officers had to follow.

Boone told one, “We are all slaughtered men.”

On

the other side of the river, now committed, Todd hastily organized a line of battle.

Most men dismounted and formed several rows deep. Todd and McGary commanded in the center, Trigg on the right, and Boone on the left. Todd and Trigg led mounted from the front. Boone advanced

with his men on foot.

By

the time the lines neared of the hill, withering

fire erupted from ravines running

along the flanks and from the top.

Todd and Trigg were almost immediately shot out of the saddle. The

center and right were broken after

moments under fire and began a disorderly

retreat taking casualties as

they ran.

Boone

and his men, taking advantage of what

cover they could find, continued to advance until he discovered his flank was exposed by the collapse of the center and he was

taking enfilading fire. Boone ordered a retreat. He captured

a loose horse on the battle field and gave it to his son Israel, who had been fighting alongside of him. Israel took a ball to the neck almost as soon as he got up. Boone, seeing his son dying, grabbed the horse and hiding

himself by practically laying down on one flank, managed to get away.

The

militia lost 72 dead, 11 captured, and dozens wounded, one of the highest losses as a percentage of men

engaged in the entire Revolution. By

contrast the Rangers and native auxiliaries lost only 7 men. The battle was a disaster.

In

November Clark, who was stung by criticism that he had somehow “allowed” the

ill advised attack even though he knew nothing of it, was able to raise a large

militia force of Kentuckians vowing vengeance.

He crossed the Ohio and chased Indians who melted into the forests. He burned several villages along the Miami River that the Shawnee, who had

not even participated in the Battle of Blue Licks, had abandoned. Clark returned

home claiming a fruitless victory in

the last American offensive of the war.

Even

when word of the Treaty of Paris

finally reached the frontier late the next year, it hardly changed anything. The

British refused to honor treaty

provisions for the evacuation of

Fort Detroit and other western outposts. And they

never ceased to hope that using Indian allies that they could lay claim to the trans-Allegany west,

or at least achieve a native buffer

state. They continued to arm and

supply warriors who continued to make small

scale raids into Kentucky and harass

traffic on the Ohio.

In

1786 full scale war re-erupted. General

Benjamin Logan, the officer who had never made it to Blue Licks, commanded

a large force of Federal regulars

and Kentucky Militia against Shawnee villages along the Mad River. Several were burned, crops and stores destroyed, and

women, children and old men killed. A

Kentucky militia man also tomahawked Shawnee chief Moluntha under the mistaken belief he had been at Blue Licks. Logan’s actions spawned and even wider Shawnee uprising and bloody raids

across the frontier.

After

armies under General Josiah Harmar in

1790 and General Arthur St. Claire in

1791 were both routed with heavy losses,

President Washington ordered General

“Mad” Anthony Wayne to form the Legion

of the United States, a well-trained

force and put an end to the situation in 1793. The following year he defeated the British-supported

confederacy of tribes led by Little

Turtle and Blue Jacket at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

In

1795 the Treaty of Grenville forced

the tribes to recognize American

sovereignty over the Northwest

Territory and ceded large swaths of

land in Ohio. The same year The Jay Treaty reaffirmed the duty of

the British to abandon Detroit and other western posts. The British hauled down their colors there in

1796.

But

even then the peace was not permanent. Tecumseh

and his brother the Shawnee Prophet

forged a new confederacy and rose again. He was defeated at the Battle of

Tippecanoe in 181l by a large force under William Henry Harrison. And despite setbacks, British ambitions in

the west were finally ended after the War of 1812.

Looking at all of this, Native American historians

tend to view the whole period from Braddock’s Retreat in the French

and Indian Wars in 1764 to the end of the War of 1812 as a single Fifty

Years War on native independence.

No comments:

Post a Comment