|

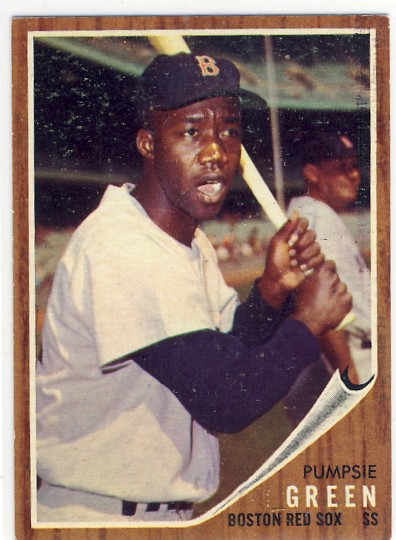

Pumpsie Green batting, running, and fielding for the Boston Rec Sox.

|

Sixty

years ago today the Boston Red Sox did

it at far from home at Comiskey Park in

Chicago on July 21, 1959 in a losing

game against the red hot White Sox, the eventual American League Champions that year. The BoSox,

languishing below .500 and way back in the pack,

sent Pumpsie Green into the game as

a pinch runner. He had no effect on the 2-1 loss to the Pale Hose.

But that brief appearance made Boston the last of the pre-expansion Major League Baseball teams to

field a Black ballplayer. That was more than 12 years after Jackie Robinson took his famous bow

with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

You

would have to be a very hard core

baseball nerd indeed to have ever heard of Pumpsie Green. Although by all accounts a very nice and rather

shy man who returned to his California home town to become a high school coach

and beloved figure, Green was barely a journeyman

ball player with a short 5 year Big

League career with generous time back down in the Minors who never became a regular in the lineup and was used mainly a utility

infielder and pinch runner.

|

Pumpsie Green 1960 baseball card.

|

Contrast

that record with those who broke the color

barrier at other teams. Owners

generally followed the Dodger’s Branch

Rickey in introducing top flight players from the Negro Leagues in hopes that real star talent that could boost their teams in the pennant races would eventually win over

all but the most hard core racists among

their fans. In addition to the legendary Robinson other

team firsts included standouts and some future

Hall of Famers like Cleveland’s

Larry Dolby (1947), Hank Thompson for

the St. Louis Browns (1947) and the New York Giants (1949),

Monte Irvins also with the Giants on the same day as Thompson, Minnie Miñoso

for

the White Sox (1951), Ernie Banks

with the Chicago Cubs (1953), and Elston Howard in New York

Yankee pinstripes (1955).

|

Long time Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey.

|

This

was not an accident. The Red Sox

organization never wanted to integrate and

resisted all pressure to do so for

as long as possible. Whether this was

due to the personal racism of owner Tom Yawkey and

the team’s long time manager and Yawkey’s drinking buddy, Texas born and raised Mike “Pinky”

Higgins is the subject of much debate. Higgins often gets more of the blame and

after his death some of his former players recalled racist comments. Baseball

writer Al Hirshberg reported in

his 1973 history of the team that in the ‘50’s Higgins had bluntly told him “There’ll

be no niggers on this ball club as long as I have anything to say about it.”

But even before Higgins’s ascent, Yawkey

had proven reluctant to hire Blacks. Not

that he did not have the chance. In fact

the Red Sox had first crack at Robinson and other future greats. Robinson’s first Major League try out was at Fenway Park on April 16,

1945. As he was finishing up someone

yelled from the stands “Get that Nigger off the field!” It was a humiliating moment for Robinson who

remembered it with bitterness. Some have

attributed the shout to Yawkey himself.

Others have scoffed at the idea that the elegant Yale educated owner would have said anything that crude even if he

agreed with it. But he clearly oversaw

an organization where it was possible and perhaps encouraged. The team also passed up first rights to Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.

Under Yawkey and Higgins the Red Sox did

develop a number of Black prospects in their minor leagues system, but

consistently traded them away for less promising white player or released them

outright before they could hit the majors.

The team pointedly kept its spring

training home in Tempe, Arizona which

had no hotels that would accommodate Blacks who would have to

stay in Phoenix 15 miles away while

they were being evaluated for the big team.

|

Was Manager Mike Higgins really behind Boston's long hold out against Black players?

|

Boston always had a reputation as a liberal city in regard to race. Famously it was a hot bed of resistance to the Fugitive

Slave Law and a cradle of

Abolitionism. Rev. Theodore Parker and a cabal

of wealthy abolitionists had secretly bankrolled

John Brown. Senator Charles Sumner was

a lion of abolitionism and a Radical

Republican bane to Abraham Lincoln and

his hopes of re-integrating the South back into the Union.

In the post-war Reconstruction Era most of the Massachusetts Congressional delegation firmly supported Black citizenship and voting rights in the south and the generous 40 acres and a mule policy of the Freedman’s Bureau. Years in

the future, in 1967 the state would elect Edward

Brooke the first Black in the

Senate since Reconstruction.

But often forgotten were the anti-abolitionist riots that the righteous minority in the city had to

face. Also forgotten is the strength and

appeal of the anti-immigrant and anti-Black

Know Nothings in the 1850’s. The liberal, Republican and largely Unitarian

elite began to leave the city for the leafy suburbs in the late 19th

and early 20th Centuries leaving the

city itself a Democratic power house and

populated largely by Irish, Italian,

and other immigrants and their dependents.

It had, compared to other Northern cities, a small Black population

which was bitterly resentenced in the teaming white working class neighborhoods.

Just how deep the animus ran would be shown years later when Southie and other white working class

neighborhoods erupted into years of sometimes violent opposition to

bussing to desegregate the school system.

Liberal whites in the suburbs might have watched the Red Sox

on TV, but the seats at old Fenway

were filled by those working class whites who, we are told, would stage a revolt if they saw Black

players on the field. Perhaps. But other cities had similar resistance and

managed to integrate after overcoming initial resistance.

The boost that talented Black players

provided to teams was one big reason.

Boston suffered from its long holdout.

Under Higgins’s managership after early marginal successes the team went

from a perennial powerhouse and pennant contender to a consistent bottom dweller in the standings. Sports writers were beginning to blame that

on Higgins’s stodgy management style

and on his refusal to bring on talented Black players.

Perhaps that is why with the team

languishing again in the cellar, and days after the usually fawning Boston

newspapers began singing the song about missing great Black players that Yawkey

finally canned Higgins as manager and

replaced him with Billy Jurges. But he kept his good drinking buddy close

to him in senior management as a special advisor. The move allowed Higgins to never be

personally responsible for introducing a Black player on the team.

Later that summer pitcher Earl Wilson was also called up. Neither player set the league afire—perhaps

an “I told you so” moment for Higgins.

The Red Sox finished the season a dismal 100 games under .500 and

staring up at the White Sox and the hated Yankee

dynasty that would go on to dominate Baseball through much of the ‘60’s.

|

Fenway Park circa 1960 on a post card. The ball wasn't the only thing white....

|

Early the next season Higgins talked

himself back into the dugout where

he managed his Black players without ever personally insulting them but

lavishing them with scant affection. After retiring as a manager in 1962 with a

career record only two games over .500, Higgins was promoted to officially

become General Manager. As Yawkey’s confidant he had effectively been

acting in that capacity without portfolio

for years.

The Red Sox went on to field Black

Players, including some stars. But they

always tended to have fewer on the field than most teams. And they generally preferred dark skinned Latinos to African Americans. Sometimes it seemed that they were back

sliding. As late as 2009 they began the

season with not a single Black player in the season starting lineup.

Meanwhile demographics in Boston have

changed. Over the last 30 years Yuppies and their descendents Hipsters have returned to the city and recolonized neighborhood after

neighborhood squeezing the old ethnic

enclaves and Black neighborhoods alike.

Many Blacks have been pushed into surrounding towns and suburbs. The Yuppies and hipsters became noisy and

loyal members of the Red Sox

Nation. Indeed when I was last in

Boston in 2007 it seemed like by law no male in his 20’s or early 30’s could be

seen on the street without a Red Sox cap

beat up just enough to indicate that it sat on the head of a non-tourist. They buy out the increasingly expensive seats

in Fenway Park displacing the working class fans that kept the team afloat in

its leaner years.

The Yuppies and Hipsters tend to be more

tolerant, or polite, about race than the denizens of Southie. Yet attendance at Fenway remains

overwhelmingly white, rivaling the bleached look of fans in Atlanta and Houston where Astros management

once hired Black vendors to sit in vacant seats in the boxes behind home plate

to give the illusion inclusiveness on national TV during a playoff series.

As for Pumpsie himself, he was uncomfortable

even talking about his experiences.

Elijah Green was born on October 27,

1931 in Boley, Oklahoma. He got his unusual

nickname from his mother. His family relocated to Richmond, California largely to give their athletic sons the best possible opportunity. Two brothers were

drafted into the National Football

League and Cornell Green was a

long-time safety on the Green Bay Packers. Pumpsie also showed promise as a three letter man at El Cerrito High School.

Green considered basketball to be his best sport, but baseball seemed like the best

ticket to a professional career. He attended the two year Conta Costa College to which his high school coach had moved. In his second year there he tried out for and

was signed into the system of the Oakland

Oaks of the Pacific Coast League.

In 1954, Green batted .297 in his second

season with Oaks affiliate the Wenatchee

Chiefs, and was promoted the next year to Stockton Ports. Green’s contract was purchased by the Red Sox organization during the 1955 season but

he was allowed to finish out the season in Stockton. He worked his way up the Reds organization as

a short stop and second baseman over the next three

years. All the while he saw more

talented Black prospects traded away from the organization.

After spending the 1958 campaign with

the Minneapolis Millers, Green was

called up to Red Sox spring training the next year. As one of the few remaining Black prospects

in the system, he drew a lot of attention and some largely unmerited press hype. But he was sent back to Minnesota where for

the first half of the season he played some of the best ball of his career,

hitting .320 in 98 games.

He never got enough playing time with the Red Sox to get into much of a groove with his bat or glove, although he was valued for his speed on the base paths. He only played 50 games for the rest of the season and hit an anemic .233. All of his starts were at second base, not his natural position as a short stop.

He never got enough playing time with the Red Sox to get into much of a groove with his bat or glove, although he was valued for his speed on the base paths. He only played 50 games for the rest of the season and hit an anemic .233. All of his starts were at second base, not his natural position as a short stop.

In 1960 he settled into a role as a

utility man giving regular starters a rest or, because he was a switch hitter for use against left-handed pitchers. He appeared in 133 games, some of them as a

pinch runner and divided his time between second and short.

Green was off to a relatively hot start

in 1961 and looked for a while like he might break into the status of a regular

starter. But in May he was hospitalized

with appendicitis and put on the disabled list for a month. He was still in physically weakened condition

when he came back to the club. Still he

put up his best numbers in the Majors--six home runs, 27 RBIs, 12 doubles, and four stolen bases.

Despite the promise the 1962 season was

a humiliation. Famously after a weekend

sweep by the hated Yankees in New York City Green and his buddy pitcher Gene Conley jumped off a team bus that was stuck in Bronx

traffic and disappeared. The pair was found two days later at Idlewild International Airport trying

to board a plane for Israel, with no

passports or luggage. The famously bizarre episode became the butt of

comedian’s jokes but was never explained.

The next year Green was traded to the New York Mets for the 1962 season. The Mets kept him on their Buffalo Bison affiliate roster most of

the year. He made only 17 spot

appearances with the big league club and swung a bat for the last time as a

major leaguer on September 26, 1962.

Before

returning permanently to the Minors for the final two years of his career,

Green racked up a

.246 batting average with 13 home runs and 74 Runs Batted In (RBI) in

344 games.

After

retiring from organized Baseball Green became the baseball coach and a summer school

math teacher, and councilor at Berkeley High School in Berkeley, California. He settled back in El Cerrito with his

longtime wife, Marie. He was a respected, even beloved, citizen

of his adopted hometown which honored him in 2012 with a proclamation for his “Distinguished status in the history of Baseball.”

|

Throwing out the first pitch at Fenway 50 years later.

|

The

Red Sox organization was getting some flak

for never recognizing his contribution in integrating the team. Back in 1959 the often loquacious Yawkey had

not one word to say in the press about the event and management had done damn

little to highlight it ever since.

Finally on April 17, 2009 at the beginning of the season 50 years after

of his debut, Green was invited to throw

out a first ball. He was invited back to do the same before Jackie Robinson Day in 2012 and was

among the old timers in attendance

for Fenway’s 100th anniversary

celebrations later that month.

But

there has never been a Pumpsie Green Day. And don’t hold your breath for the Bobble Head promotion.

Just

five days ago on July 17 Green died at the age of 85 in California earning

brief obituaries in the New

York Times and Washington Post and a longer notice

in the Boston Globe.

No comments:

Post a Comment