Bettty Freidan, the iconic founder of the second wave feminist movement, envisioned a march that would "get the attention of the press" but had to fight dissent in the ranks.

In 1969 Betty Freidan thought it was a good idea to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment, which effectively gave American women the right to vote. Freidan, the acknowledged founding mother of the modern Feminist Movement was inspired by Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party who’s relentless and daring militancy pushed the long sought dream of suffrage to reality. In turn she inspired the Women’s Marches that protested attacks on hard-fought for gains that drew hundreds of thousands to the National Mall in 2013.

Freidan began advocating and trying to organize “something big, something so big it will make national headlines” to galvanize the movement to new levels almost a year in advance. She encountered a lot of resistance, even in the National Organization for Women (NOW), the country’s main feminist organization of which she was a founder. Many members and leaders regarded a mass protest as too radical. It also reflected tensions in the movement, barely 10 years old, between middle class white women and professionals and younger radicals comfortable with confrontation through experience in the anti-war movement and who were tending toward separatism.

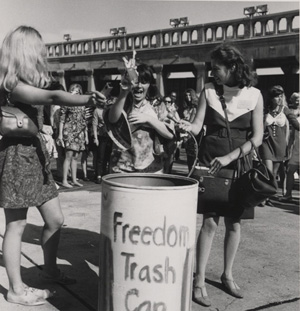

Older feminists thought the antics of young radicals like the burning of symbols of male domination outside the 1968 Miss American Pageant had discredited the movement. The handful of women who participated were dubbed "bra burners" and the press portrayed the whole movement with the title.

In the eyes of some older activists these young Women’s Libbers as they were mocked in the press, had already done damage to the movement with small, attention grabbing protests. Most famous was the Bra Burning Protest held outside the Miss America Pageant in 1968. The media had seized on that with a frenzy and Bra Burner had become synonymous with all feminists in the minds of much of the public.

While the NOW Board of Directors was slow to sign on, Friedan plunged ahead trying to plan and organize the event. At first she used almost leaderless consciousness raising groups, a hallmark of ‘60’s feminism. But sessions soon broke down in controversy between factions. Even a month before the planned protest it was still mired almost to stalemate between the middle class “founders” and the young radicals.

A poster promoting the New York Women's Strike.

Eventually Friedan’s prestige among both groups and some careful compromising won out. NOW endorsed the action and the Call went public.

The next hurdle was getting a permit from the City of New York for a planned march down Fifth Avenue, the sight of historic suffrage demonstrations before World War I. The city flatly refused. In response Friedan defiantly recast the protest as the Strike for Women’s Equality and vowed to go on with or without a permit.

Publicity surrounding the refusal galvanized support among activists of both factions. Around the country NOW chapters and independent radical feminist groups planned actions in a score of cities.

In New York the Strike was set for Tuesday, August 26, 1970 at 5 pm to accommodate the thousands of women office workers who would pour out of Manhattan buildings at that hour. Police attempted to confine the raucous protest to the sidewalks of Fifth Avenue. NOW signs demanding equal pay for equal work, abortion access, and other mainstream issues, mixed with homemade signs both whimsical and angry. Friedan and other leaders could only speak through bullhorns and were often drowned out by spontaneous chanting. The crowd soon swelled to over 20,000 and the police could not keep them out of the streets. Although few, if any, arrests were made, TV film footage broadcast later that night and the next day made it look like a near riot.

Meanwhile events in other cities were creative and often even more outrageous.

In Detroit, women staged a sit-in in a men’s restroom, protesting unequal facilities for men and women staffers. In Pittsburgh, women threw eggs at a radio host who dared them to show their liberation. Women in Washington, D.C. staged a march down Connecticut Avenue behind a banner reading “We Demand Equality”…[and] government workers organized a peaceful protest and staged a teach-in, which educated people about the injustices done to women, mindful that it was against the law for government workers to strike… in Minneapolis, women famously gathered and put on guerrilla theater, portraying key figures in the national abortion debate and classic stereotypical roles of women in American society; women were portrayed as mothers and wives, doing dishes, rearing children and doting obnoxiously on their husbands, all while wearing heels and an apron.—Wikipedia

Prestigious news commentators were not even handed in their coverage. Eric Sevareid of CBS News compared the movement to an infectious disease and ended his report claiming that the women of the movement were nothing more than “a band of braless bubbleheads.” Another CBS stalwart Howard K. Smith was equally harsh saying women had no grounds at all to protest. Small wonder that within days of the event a CBS poll showed two-thirds of American women did not feel they were oppressed.

Younger militants turned out in great number when the march seemed under attack by New York authorities. They included at least some minority women.

It first it looked like the older feminists had been right after all. The demonstrations had “played into the hands” of opponents of equality. Friedan did not think so. She brazenly declared the event a success. “It exceeded my wildest dreams. It’s now a political movement and the message is clear.”

It turned out after the initial fuss died down, she was right. The appalling response by the mainstream media actually drove the warring factions of the movement together, if still somewhat uneasily. Militancy was adopted by more and more mainstream women. NOW and other organizations were geared up for more political action and unafraid of confrontation. Within a decade most Americans had accepted much of what had been a “radical” agenda in 1969.

Despite its central part in the evolution of the Feminist Movement, the Women’s Strike for Equality is not well remembered today.

No comments:

Post a Comment