On March 28, 1796 the Bethel Methodist Episcopal Church opened in Philadelphia. It was the first American church organized by and for African Americans.

In 1787 Richard Allen and other free blacks were worshiping at the city’s St. George Church. After angry parishioners literally dragged praying blacks from their knees, a small group withdrew determined to found their own congregation where they could worship safely and without interference.

Allen had been born a slave to a wealthy Quaker family in 1716. As a child he was sold with a brother to another Quaker, Stokely Sturgis. He was well treated by the family and encouraged to read and write. At the age of 17 he received permission to worship at the Methodist Episcopal Church. Impressed that the young man’s work habits were not, as the prevailing opinion of the time would have it, ruined by Christianity, Sturgis allowed Allen to invite the charismatic Methodist preacher Freeborn Garretson onto his property to preach to his slaves. The master was so impressed, he converted to Methodism himself.

Garretson, like many other Methodists, believed slavery was wrong and convinced Sturgis to allow Allen to buy his freedom. Working on his own time in addition to his service to the Quaker family, Allen saved up $2000 dollars in devalued Continental currency and bought his freedom.

By 1783 the new freeman was touring Pennsylvania and neighboring Delaware

counties as an informal missionary

preacher. In 1784 Allen attended the Christmas Conference at which American Methodists formally separated themselves from the Anglican Church.

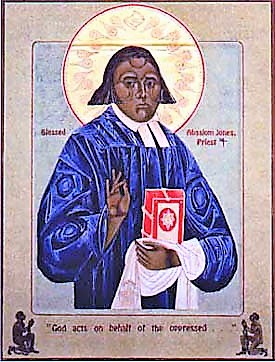

He joined St. George’s in Philadelphia in1786 and was licensed to preach, and allowed to organize early morning prayer services for other free blacks. As the group of worshipers grew, so did the discomfort among white members. Black members were to be segregated in a newly built balcony. Shortly after its completion, Allen, his regular confidant and supporter Absalom Jones, and other Blacks knelt to pray at Sunday services on the main floor as had been their custom when white members insisted that they vacate for the balcony and began physically dragging Jones to his feet. After prayers Allen and Jones and their supporters left vowing never to return. After the 1787 scuffle the free blacks determined to find a location for their own church.

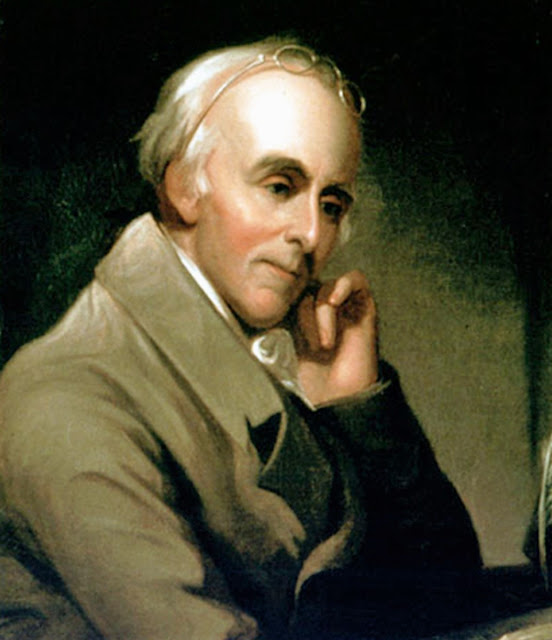

They raised money for a lot

on Sixth Street near Lombard the same year and purchased it in Allen’s name. Universalist Dr. Benjamin Rush, the founder of the first

American abolitionist society, was among the first and most generous donors.

Even President George Washington,

probably at the urging of Rush, a friend and signer of the Declaration of

Independence, made a contribution. The

property was the first real estate owned

by Blacks in the United States.

A former blacksmith shop was purchased and hauled by oxen to the lot. Members went to work repairing and improving the structure.

The congregation however split about affiliation. A group led by Jones preferred to join the Episcopal Church. Allen

steadfastly believed that the simplicity

of Methodist worship was more suitable for

blacks. The parting was largely amicable. Jones went on to become the country’s first black ordained Episcopal Priest

and founded St. Thomas Parish.

Both infant congregations began the slow process of raising funds for permanent church buildings. The devastating Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793 suspended those efforts. Both Allen and Jones worked heroically at the side of Dr. Rush nursing the critically ill and dying. When an account of the emergency was published neglecting to mention either man or the services of their communities, they wrote a pamphlet which forced a revision in the account. The pamphlet was the first thing copyrighted by Blacks in this country.

The converted blacksmith shop was consecrated as a church by sympathetic Methodist Bishop Francis Ausbury and named Bethel on March 28, 1796. Although licensed to preach Allan was not ordained until 1799 when he was made a Deacon, becoming the first Black man ordained as a Methodist in the United States.

But even as the church grew to more than 450 members early in the 19th Century, most Sunday services were still conducted by white ministers from St. George’s. Over time the relations between the two churches grew strained and St. George’s even tried to seize the keys and force the deed into the hands of the Methodist Episcopal Church name. On at least one occasion angry parishioners jammed the church aisles to prevent a white minister from taking the pulpit.

The emblem of the African Methodist Episcopal Church--the first Black denomination in the U.S.In 1816 Allen and other Black Preachers from Pennsylvania Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey met to form a new denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Allen was elected Bishop. The sympathetic and supportive Bishop Ausbury returned for his consecration.

The new denomination spread under Allen’s guidance and was for many years the largest Black religious body. Allen and his friend Jones continued to collaborate for the benefit to the Black community, most famously banding together to protest the establishment of the American Colonization Society (ACS) in 1817. Backed by many white liberals, the ACS sought to raise money to “repatriate” Blacks to Africa, a place totally alien to the American born.

The fourth Bethel building on the original site was erected in 1889 and features a statue of Richard Allen in a small park on the grounds. Allen and his family rest in a crypt in the basement that is an object of pilgrimage.Allen died on March 26, 1831 almost exactly 35 years to the day of the consecration of the blacksmith shop church. By then Bethel was in a fine new building which could seat hundreds. Allen was entombed there. Over time, two more church buildings were erected at the same original site, but Allen’s tomb, including members of his family, remains on the property.

In Philadelphia Allen’s church is

known as Mother Bethel. The current handsome stone building was dedicated in 1889 and underwent restoration

in 1991. You can see it for yourself. The current address is 419 Richard Allen Ave.