Roy Eldridge, trumpet; Oscar Pettiford, bass; and Billie Holiday, thrush in the Esquire Jazz All Star concert at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

Eighty years ago on January 18, 1944, thirty or so years after Jazz burst from the streets of New Orleans and into the speakeasies and hearts of Americans, the music finally crashed through a glass ceiling into respectability as an art form with an all-star concert broadcast from the hallowed stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.

On hand playing on their own and in collaboration were Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Artie Shaw, Roy Eldridge, Jack Teagarden, Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, Red Norvo, and a couple of girl singers—Billie Holiday and Mildred Bailey.

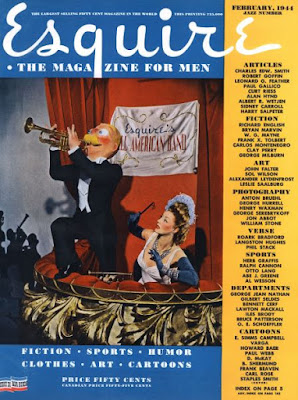

The poster promoting the concert.

The concert had its origins in the desire for the magazine to carve out a new niche among publications. Esquire had been founded in the depth of the Depression in 1933 as a men’s magazine competing in a genre that had been dominated by smoker magazines along the lines of the venerable Police Gazette that mixed sports, scandal, sensationalism, titillating but safely risqué humor, and pictures of pretty girls clad a scantily as the Post Office would allow. The new magazine was produced on slick paper with modern design elements like industry giants Life, Look, and The Saturday Evening Post. It aimed for a more urban and upscale readership than its competitors.

In its first few years the magazine struggled to find and identity and audience. But by the early 1940’s it had hit on a successful format built around the alluring Vargas and Petty Girl illustrations and contributions of fiction and reportage by literary heavy weights like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Alberto Moravia, Andre Gide and Julian Huxley. The magazine was becoming a hot commodity.

In the midst of World War II as war production cut back on the consumer products which were the back-bone of its advertising, the publisher and editors noted that per copy sales were still strong, especially among GI’s. Looking forward to when those men would be coming home and when the cornucopia of consumer goods for them would come gushing to market, they wanted ways to secure continued loyalty of the reader base.

One way was to appeal to the cultural interests of the men. What were they interested in? The answer was on the radio every night. Jazz and more jazz. The Big Band Era was at its height, but smaller combos playing traditional jazz were still popular. Why not initiate a Reader’s Poll to pick favorite performers on all of the instruments, singers, and band leaders?

Esquire touted its jazz at the Met program on its cover.

The first poll was launched with great fanfare in 1943 and the results, published in the December issue of the magazine, attracted wide attention. And some scandal. There had been previous jazz popularity polls. But they had been based on feedback from record stores, which were dominated by the young, overwhelmingly white bobbysoxer fans of the Big Bands. The results had inevitably skewed to white musicians.

But the Esquire poll sampled the more sophisticated audience of the magazines targeted demographic. Many newspaper critics were shocked when the results were heavily skewed to Black artists.

On the other hand, many of the most hard core jazz fans clustered in the bohemian ghettoes of the big cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, found many of the honorees already passé and accused the magazine of ignoring new, cutting edge sound emerging from the small stages of smoky nightclubs.

Controversy, however, generated interest. Publisher David Smart came up with the idea of an all-star concert featuring poll winners. He moved with astonishing speed to set the event up. By designating the show a benefit for the Navy League, a platform for War Bond sales, and securing the early interest of Armed Forces Radio, he wrapped the event in suitable patriotism which unlocked the doors of the Metropolitan Opera House, previously a guardian of high European culture.

New York's highbrow temple--the original Metropolitan Opera House.

Ticket sales were predictably brisk. The New York Times reported that $650,000 was raised by ticket sales and 3,600 bonds were sold. 1944 Esquire All-American Jazz Concert at the Metropolitan Opera House was broadcast on NBC Blue network and around the world on Armed Forces Radio (distributed on discs) as part of the popular One Night Stand.

The legendary show centered on Armstrong and his early New Orleans style opening up to later mainstream jazz and the Big Band leaders playing together in tighter, smaller combos. Missing almost entirely were the early strains of what would become the dominant post-war expression of jazz, bebop, only hinted at by a few licks by Coleman Hawkins.

That first show would be followed by two more in ’45 and ’46. But it was the first one that took on legendary proportions.

That first show would be followed by two more in ’45 and ’46. But it was the first one that took on legendary proportions.

Licensing issues in the United States prevented domestic release of recordings. But when the European copyright on the Armed Forces Radio transcription disc recordings expired, the whole concert was issued on a double LP album in the Czechoslovakia in 1998. Despite the less than stellar recording quality, the set is available in this country as an import, and many consider it an essential recording for anyone interested in the history and evolution of jazz.