| A political deal with Democrats funded the school. |

When

I was cracking open an American history text in Cheyenne about 1965 African-Americans were covered in generous page or so in the

400 page tome. The contents can be summed up thusly—Harriet Tubman, Fredrick Douglas good for a short paragraph each; Lincoln frees the slaves and everyone is happy; uppity Blacks and carpetbaggers

wreck horrible vengeance on the

defeated South; Booker T. Washington establishes

the Tuskegee Institute and one of

his teachers, George Washington Carver

invents a thousand things to do with the peanut

and saves the economy of Georgia. The latter two, Credits to Their Race, got by far

the most ink and even their pictures

in the book.

Washington

was the Black man Whites loved, and the one they anointed as the spokesman for the race.

And why not. In order to grow his school in the hostile

soil of the post-reconstruction South,

Washington made a series of compromises,

not the least of which was refusing to

advance arguments for the restoration

of black suffrage or challenging

White authority in any way. Instead,

advocated that Blacks educate themselves—particularly

in useful pursuits like agriculture and teaching—work hard, elevate their moral behavior, and prove themselves to Whites for years

before pressing for expanded rights.

It

was a song even Southern Democrats yearned

to hear from Black folks, and it enabled Washington to gather financial support and endowments

from some of America’s wealthiest men

to grow his school into a major

institution in just a few years.

Of

course his consistent conservatism

would eventually draw the scorn of more aggressive Black leaders like W. E. B Du Bois, author of The Soul of Black Folks and a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP). That criticism would be echoed by new generations of Black activists and

the scholars who emerged from the Black Studies departments of American Universities since the 1960’s.

It

was on September 19, 1881 that a small Normal

School for Colored Teachers opened its doors—or door, it only occupied one run-down shack—to students

for the first time in Tuskegee,

Alabama.

The

previous year a local Macon County Black political leader, Lewis Adams, agreed to abandon

his traditional allegiance to the Republican

Party and support two White

Democratic candidates for the Alabama

legislature. It was one of the last

elections in which Blacks, supported by the continued presence of Federal

troops under Reconstruction were

able to vote in substantial numbers. Thanks to the re-capture of state and local

governments by Democrats, the era of Jim

Crow was about to strip Blacks

of almost all of their Civil Rights.

Whatever

reason Adams had for “selling out”

to the Democrats, he was rewarded with a $2000 appropriation to found a new Normal School. Samuel

Armstrong, President of Virginia’s

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, the successful model for the new school, was asked to recommend a principal with the full expectation that the candidate

would be White. Instead, Armstrong

recommended a 25 year old Black graduate of Hampton—Booker T. Washington.

|

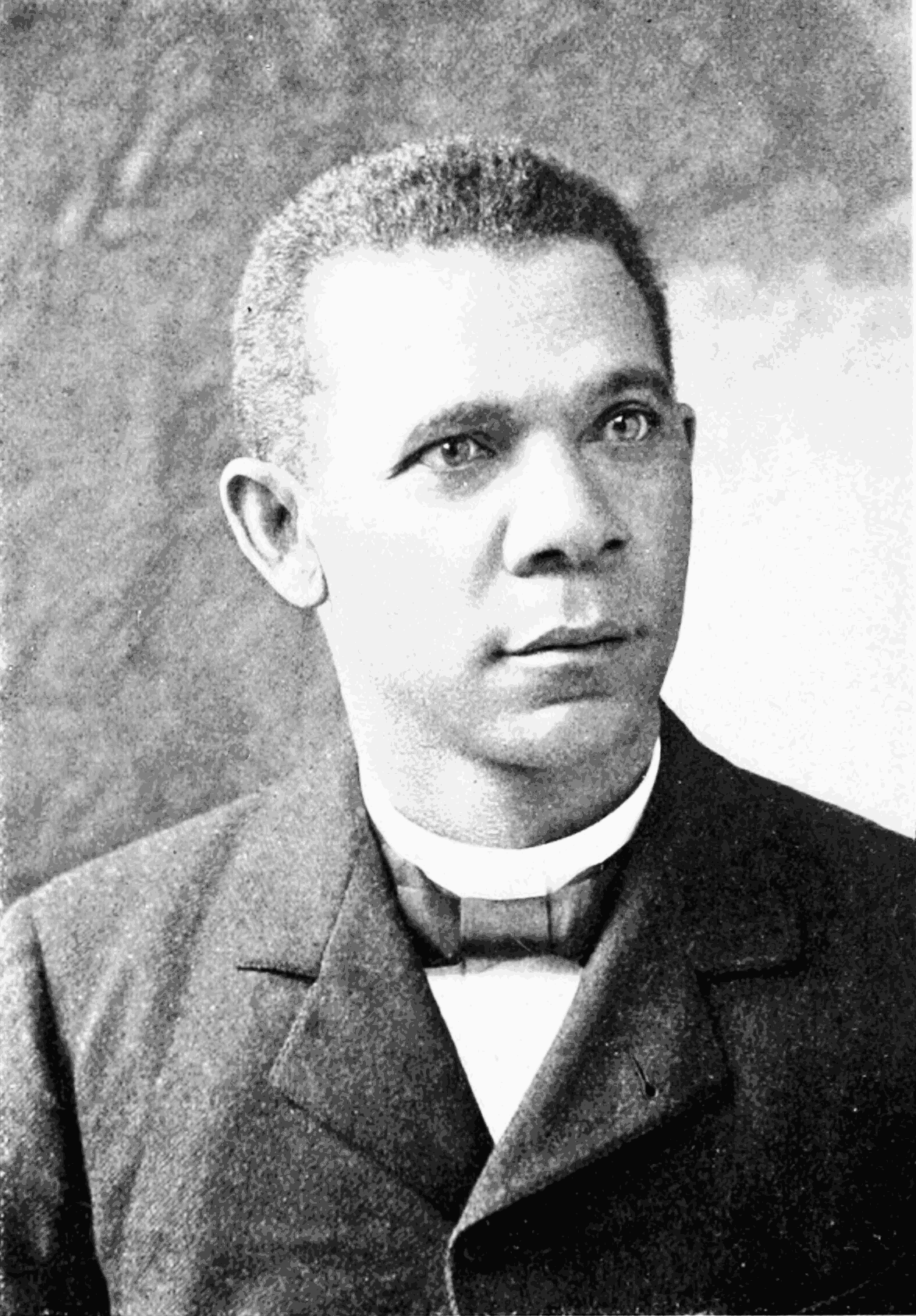

| Young Booker T. Washington. |

Washington

had been born a slave in Hales Ford,

Virginia April 5, 1856. Like many plantations children, his father was white, but never identified. He was just nine years old when the Civil War ended. After emancipation

his mother Jane resettled in West Virginia where she at last could legally marry her long time husband a freedman

Washington Ferguson. The boy took

his step-father’s first name for his

last.

As

a youth he worked in local coal mines

and in a salt furnace saving a small

amount of money to travel to Hampton Institute for an education. He worked his way through that school and

then enrolled in Wayland Seminary, a

Baptist theological school, in

1876. He abandoned the pursuit of the ministry and returned to Hampton,

where he had been an outstanding student, to teach.

July

4, 1881 is usually sited as the foundation

date for the new school. But classes

did not actually begin until

September. Washington took the reins of

a school with just enough money

to pay him and a couple of instructors for one

year. The legislative grant had not covered either land or buildings. The ramshackle

old church that the founders had secured

was obviously unsuitable for a

lasting institution.

Washington

showed the skillful administrative

and fundraising abilities that

marked his career by securing a loan

from the White treasurer of the

Hampton Institute to buy a plantation

on the outside of town. He opened the

school there in 1882.

By

1888, just seven short years after moving to the plantation location, the Tuskegee Institute was famous. It encompassed

nearly a dozen buildings on over 540 acres had more than 400 students enrolled. How did Washington accomplish this astonishing transformation?”

Two

ways. First, he was a relentless fund raiser and not afraid

to directly approach the richest and

most influential men in the nation for support. He knew

just what to say to them to tug at what charitable

heartstrings they might have while assuaging

any fear that they may be abetting a

Black uprising. Eventually his list

of donors grew to include steel magnate

Andrew Carnegie, and Central Pacific Railway tycoon Collis Huntington.

He enjoyed political support

and protection both from Alabama

White Democrats and national Republicans

like William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt, who would famously invited him for dinner at the White House.

Secondly

was the labor of his students. Students were expected to work, and work hard, in exchange for their education.

It both fit in with Washington’s philosophy that work was ennobling and provided him the hands that built his buildings, tended the farm that produced the food that was eaten,

engaged in numerous crafts, cooked and served, cleaned and catered to his every whim.

Students

were roused from their beds at 5:30

and kept running between classes,

chores, study time, and prayer until 9:30 at night. Except for the Sabbath, which was expected to

be devoted to services, Bible reading, and reflection, there was no

free time, no recreation. Washington

feared that idle hours would tempt his students into crap games, drinking, chasing women,

and general debauchery which would ruin them, and worse, bring disgrace upon the school and the

race.

Despite

the rigorous demands, ambitious students from across the

South got to Tuskegee any way they could get there. They found dedicated and gifted

teachers like Olivia Davidson,

the vice-principal who became Washington’s

second wife, and Adella Hunt-Logan an English teacher and school librarian who also became a leading Black women’s suffragist. Programs in agriculture and the “useful

manual arts” prepared them for life in the South.

| Tuskegee was literally with the labor of its students. |

Within

a few years graduates were spreading

over the South, improving Negro

schools and founding new ones. Agricultural

extension activities brought modern

farming techniques to Blacks who were able to hold on to their land and avoid being knocked back down to the semi-slavery

of share cropping.

By

1890 the White Democratic counter-revolution

was complete across the South. Blacks

were once again disenfranchised. Jim Crow and the reign of terror of the lynch

mob crushed Black hopes and expectations.

In less than ten years from its founding, the social climate that had given birth to the school changed. Former

Southern White allies, who had seen the school as a balance against more

threatening Black advancement, now were turning on it and regarding it with

suspicion.

Washington

was keenly alert to the dangers. He took

the opportunity provided by an

invitation to give a speech at the opening of the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta to put forward the much

publicized Atlanta Compromise in

which he, on behalf of Southern Black

leadership pledged explicitly to

accept White rule, refrain from agitation on the franchise and other issues in exchange

for a White guarantee to support Black

education and some degree of

fairness before the law.

Within

a few years graduates were spreading

over the South, improving Negro

schools and founding new ones. Agricultural

extension activities brought modern

farming techniques to Blacks who were able to hold on to their land and avoid being knocked back down to the semi-slavery

of share cropping.

By

1890 the White Democratic counter-revolution

was complete across the South. Blacks

were once again disenfranchised. Jim Crow and the reign of terror of the lynch

mob crushed Black hopes and expectations.

In less than ten years from its founding, the social climate that had given birth to the school changed. Former

Southern White allies, who had seen the school as a balance against more

threatening Black advancement, now were turning on it and regarding it with

suspicion.

Washington

was keenly alert to the dangers. He took

the opportunity provided by an

invitation to give a speech at the opening of the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta to put forward the much

publicized Atlanta Compromise in

which he, on behalf of Southern Black

leadership pledged explicitly to

accept White rule, refrain from agitation on the franchise and other issues in exchange

for a White guarantee to support Black

education and some degree of

fairness before the law.

The

unwritten compromise—Washington preferred the term accommodation—secured

the safety and future of the Tuskegee Institutes, although white promises of fair treatment in the courts proved

completely illusionary. It also

generated even more generous donations

from Northern industrialists and benefactors which now expanded to include John D. Rockefeller, Henry Huttleston Rogers, George Eastman, and Elizabeth Milbank Anderson.

Another

rich man, Julius Rosenwald of Sears, Roebuck and Company became a leading member of the Tuskegee Board

and funded a project which would build

500 schools in rural Black communities which would be designed by Tuskegee architects, built by student labor, and staffed

by its trained graduates.

Despite

these accomplishments, Washington’s “meek submission to White rule” drew the

scorn of a new generation of Black leaders, including Du Bois, many of them highly educated and based in the North.

Washington

spent more and more of his time on speaking

tours and on fund raising, but kept a close

grip on the management of the school as principal. The work load was visibly taking a toll on his health. On November 14, 1915 Washington died at the

school of congestive heart failure.

He

left behind a sprawling, modern campus, a wide extension system, and an endowment

of over $1.5 million. He was laid to rest on the campus.

| During World War II the school became the training center for the famed Tuskegee Airmen who became the most decorated fighter unit of the the war. |

His

school endured, even thrived. It adapted over the years to new demands, adding departments

preparing its students in many new areas.

It is now Tuskegee

University. The school famously became the training site for

the Tuskegee Airmen, the Black World War II fighter pilots who became legendary over the skies of Europe.

It

has also had its troubled moments,

most infamously as the home of the Syphilis

Study, conducted for the U.S. Public

Health Service from 1932–1972 in which 399

poor and mostly illiterate African American sharecroppers became part of a

study on non-treating and natural history of syphilis. While some

participants received treatment, a control

group was not and the disease was allowed

to run its fatal course over many years causing both needless suffering and risking

the continued infection on new victims. After the study was revealed President Bill Clinton issued a formal apology on behalf of the nation.

But

just as Washington would have, the University used the case to raise money to open a new National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care, devoted

to “engaging the sciences, humanities, law and religious faiths

in the exploration of the core moral

issues which underlie research and medical

treatment of African Americans and other under served people.”

Today

Tuskegee University is one of the flagship

schools served by the United Negro

College Fund and still one of top historically

Black universities in the country.

There are more than 4000 students

in 35 bachelor’s degree programs, 12 master’s degree programs, a 5-year accredited professional degree

program in architecture, 2 doctoral

degree programs, and the Doctor of

Veterinary Medicine program.

The

campus, including to original building, Washington’s home The Oaks, the graves of Washington and George Washington Carver and

the Carver Museum are a National Historic Site. Moton Field, home of the Tuskegee Airmen,

is a second designated Historic Site.

Graduates

of the Institute and University have included such notables as Amelia Boynton Robinson, Civil Rights

leader and the first Black woman to

run for office in Alabama; Lionel

Richie and the rest of The

Commodores; author Ralph Ellison; Air Force General “Chappie” James, the first Black to reach four star rank in the armed services; super star radio host Tom Joyner; former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin; Dr.

Ptolemy A. Reid, former Prime

Minister of Guyana; Betty Shabazz, activist

and widow of Malcolm X; and actor, comedian, and producer Keenan Ivory Wayans.

No comments:

Post a Comment