|

| That's a lot of candles, Sir. |

Today is George Washington’s Birthday except it isn’t unless you live in Virginia,

Illinois, Iowa, or New York. Those are the only states that still mark the occasion as an official stand alone holiday. And outside of the old boy’s native Virginia you would be hard pressed to find evidence

of it outside of mattress sale

ads. Nobody gets off work for it anymore.

Schools are generally in session working too hard cramming for standardized testing to do much about it. Since Ditto

machines became obsolete I doubt

if second graders even get silly Cherry Tree handouts to sniff and color. Of course, George

usually gets top billing with Abe Lincoln for the Presidents Day Federal holiday, but it’s

just not the same.

Too

bad. The Father of Our Country First in War, First in Peace, First in the Hearts

of his Countrymen, etc. was an interesting

dude. He was one of the few who can truly be said to indispensable men of their age.

While not the stiff plaster saint

devoid of common human foibles often

depicted, he had enough grit,

determination, and personal

rectitude to hold an Army in the

field for eight years against

the mightiest empire on Earth with precious few victories under his belt and yet prevail—with a little help from the French. He then helped shepherd a unique new republican government into existence and became the unifying

leader that kept the component

states from flying apart by centrifugal force. And most

astonishing of all, he walked away

from power at the appointed date and

let another take his place unchallenged

or molested. That unprecedented act set in motion 220

years of—mostly—peaceful transfers of power.

If things seem to be spinning out

of control this year, it is no fault of Washington’s example.

To begin with George wasn’t even born on February 22. He first

saw the light of day on February 11, 1731 under the old Julian Calendar then still in use by England and its colonies. He was an ambitious 21 year old in 1752 when Britain

adopted the Gregorian Calendar losing

11 dates and changing his birthday. It

must have been confusing and disorienting.

.jpg) |

| Washington's modest birthplace Pope's Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia. |

He was the son of a second marriage of a modestly prosperous planter and member of the gentry. His Father died when he was just 11 years

old and he became the ward of his older half-brother Lawrence who had

married into the fabulously wealthy Fairfax family, Virginia’s largest landowners. The boy, without a

fortune of his own, famously mooned over

the lovely Sally Fairfax, the young

wife of Lord Fairfax himself. She may, or may not, have encouraged the attentions. George wrote up rules for himself to adopt

the manners of the aristocracy and get ahead in the world.

He received a middling education from a local

Anglican priest and dreamed of following brother Lawrence into service in

the Royal Navy. His domineering mother squashed that

dream when he was 15 and the right age to have a midshipman’s birth purchased for him.

He took up surveying when

he was 17 and laid out tracts in the western counties of Virginia, sparking a lifelong

interest in western lands.

When Lawrence died in 1752—the year

of the calendar change, George came into his estate, Mt. Vernon named

for the Admiral Lawrence had served under.

The next year he was appointed a district

adjutant of the Virginia Militia with

a rank of Major.

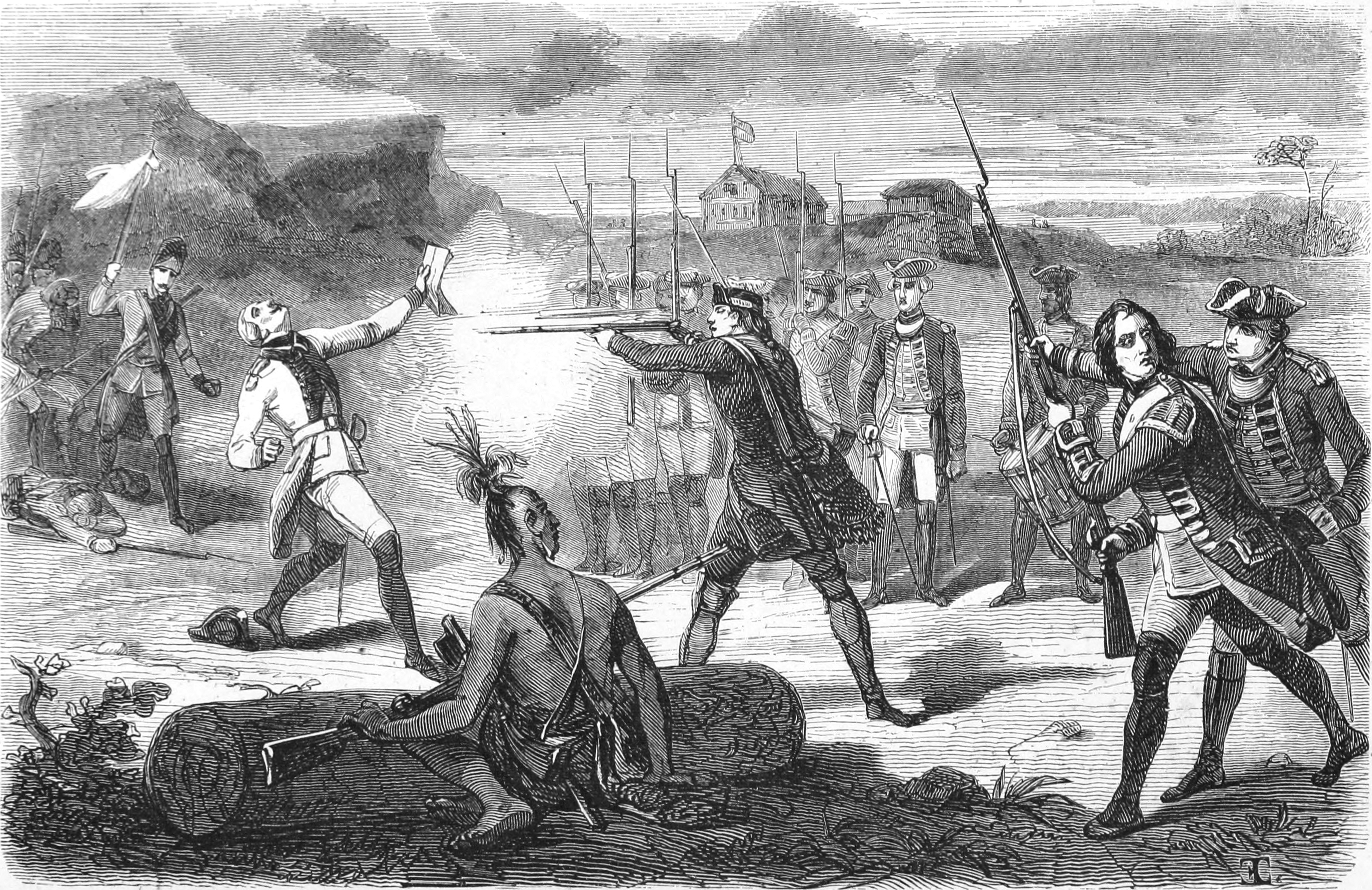

His military career got off to a fast

start by essentially starting a

world war. Dispatched to protect the

interests of the Ohio Company land

speculation scheme, Washington discovered the Ohio Company fort at the present site of Pittsburgh had fallen

to a party of French and their Native allies and that they were building their

own Ft. Duquesne. The young officer and his militia men along

with Mingo allies ambushed the French party killing most

of them including its leader Joseph

Coulon de Jumonville. Jumonville may

have been killed by the Mingos while Washington’s prisoner. The story is unclear.

Washington began to build his own Ft. Necessity near the former Ohio

Company post but his party was attacked and he was captured by the French

before he could complete it. He was

paroled and expelled by the French and allowed to return to Virginia with his

troops where he was greeted as a hero.

The French accused him of assassinating

Jumonville and after a couple of

years of diplomatic wrangling the

incident became the casus belli of the Seven Years War or the French and Indian War in North America in 1756.

None-the-less he was

exhilarated by the battle and wrote

to his brother, ““I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me, there is something

charming in the sound.”

Given Washington’s unique experience it was no surprise that he was tapped as the senior American aide to British

General Edward Braddock in 1755 for his expedition to expel the

French from the Ohio country. It was the

largest deployment to date of British Regulars who along with

American Militia and Native Allies were supposed to capture Ft. Duquesne. Because no American officer could serve above the rank of captain without

appointment from London, Washington was denied a field command at the rank of major and

reluctantly was officially listed as a volunteer

aid to the General. Braddock was a conventional European soldier with no

experience in the irregular warfare of

the frontier. He tried to push a heavy column over the mountains and through thick woods while hacking a stump road for the baggage train and artillery. It was slow going and gave the French, alerted by their Native allies, ample time to prepare.

Finally, on

Washington’s recommendation, Braddock

split his forces with a fast moving

flying column leaving the heavy construction crews and baggage behind with

a rear guard. Braddock took command of the lead column with

Washington, who had been ill with fever,

at his side. At the Battle of the Monongahela the well prepared French and Indians

ambushed the lead column, cutting it to

pieces and mortally wounding Braddock. Washington coolly rallied the British and Virginia Militia and organized an orderly retreat from what

had been a rout. He had two horses shot out from under him and his coat was torn by four musket

balls. The expedition limped home.

Washington was

hailed as a hero by his troops, but the British held him at fault for his advice on splitting the force. He was not posted to the next British expedition against the French. And his hopes for a Regular Army commission

and a scarlet coat were dimmed.

Instead Washington

was created Colonel of the Virginia

Regiment and “Commander in Chief of

all forces now raised in the defense of His Majesty’s Colony” in 1755. The regiment, known as the Virginia Blues was the first in the

Colonies to be full time professional

soldiers, who were regularly drilled

and outfitted with full uniforms and military equipment rather than ill organized, equipped and trained

Militia turned out for short service. The troops were mostly draftees from the poorest levels of Virginia society and included some mulattos and native “half-breeds”. Washington whipped them up into a respectable

fighting force and deployed them in a string

of frontier forts and blockhouses

to protect settlers from Indian raids sponsored by the

British. He led his men in brutal campaigns against the Indians

where his regiment fought 20 battles in 10 months and lost a third of its men. As a result Virginia’s frontier suffered less than that of other

colonies. Years of low level frontier

warfare followed.

In 1758 he and

elements of his regiment were part of a new

drive against the French in the Ohio country—the Forbes Expedition. Despite the ultimate success of that

expedition which ultimately succeeded in driving the French from Ft. Duquesne,

Washington saw little action and

that was an embarrassing snafu—his

men and a British unit mistook each other for the French in the heavy woods and

14 men were killed in a friendly fire

disaster.

might have

contributed to Washington’s decision to resign

his commission when he got home, but more likely was his continuing disappointment in the

British refusal to incorporate the

Blues into the Regular Army with a commission for himself. Despite his love for the military, he “retired” to manage his Mt. Vernon

estate and other properties in in December of 1758.

|

| Martha Washington was not always the heavy set, grey haired matron familiar to most of us. As Martha Dandrige Custis she was an attractive--and very rich--widow when Washington married her. |

But there seems to

have been an even more compelling motive.

On January 6, 1759 he married 28 year

old Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow with two children despite the

fact that she was older than him and he still secretly pined for Sally

Fairfax. But Martha was still beautiful, charming, and compatible. She also had shown she could capably manage a plantation on her

own. She was an excellent partner for the ambitious George and soon they were devoted to each other and he dedicated himself to raising her children when it became apparent that he would have none

of his own.

Martha was, in fact,

not just wealthy, but baring the Fairfax family, one of the richest persons in

Virginia. She brought with her not only

more plantations and property but hundreds

of slaves most of which she retained

in her name but joined the score or

so that Washington owned and were soon all working under his exacting direction. The young retired

officer had vaulted from the middling gentry to the front ranks of the Virginia aristocracy with all the prestige and responsibility that entailed.

Washington threw

himself into the management of his properties, especially the home estate at

Mount Vernon. He began expanding the modest home his brother had left into

to the impressive white mansion we

see today with additions and modifications being constantly

made. He rode the extensive grounds daily personally overseeing the work of the plantation and spent hours at his desk planning and pouring over business

matters.

Seeing other Tidewater planters beginning to suffer

from a total reliance on tobacco as a cash crop as it exhausted

the soil and yields fell off,

Washington sought to diversify his

planting and began to employ the earliest innovations

in scientific farming including crop rotation being explored by Scottish agronomists. He put in wheat, rye, oats, flax, and hemp

in addition to tobacco. He strove to

make the plantation as self-reliant as

possible building grist mills, whiskey distilleries, saw mills, a rope walk, and directed wheels and looms in the slave quarters spin

flax and wool to yarn and weave the homespun into

rough cloth. He raised fine horses, cattle,

sheep, and hogs and his busy smoke

houses produced plenty of bacon and

fine hams. The sale of his surplus production eventually rivaled

the revenue from his tobacco barns. He grew richer by the year.

| Washington at an older age was depicted as a kind slave master in this painting by Junius Brutus Stearns. |

Virtually all of the

labor was provided by his slaves, who he found more honest and trustworthy

than most hired white help. Many rose from field hands to become skilled

craftsmen, overseers, and household servants. A few were taught to read and write to

help with the details of administration. Washington was a firm and exacting master, but by the standards of the day he was a fair

one. Whipping and other corporal

punishment was sparing. And because he was interested in expanding

his slave holdings to serve his bustling properties, he seldom sold his slaves or separated

families. After all, he preferred to

breed slaves rather than buy them. And unlike so many other masters, Washington

did not use his female slaves as a private

harem. His rectitude and loyalty to

Martha prevented common sexual abuse that

was rife among slave holders.

Still, no matter how you cut it, there is no

denying that the vast wealth that Washington amassed on the base of his

brother’s estates and his wife’s properties was the direct result of slavery.

Despite all of this,

Washington was still in debt to his British creditors of the importation of

luxury goods for his household, especially in the early years of his marriage

as he sought to establish his social standing.

When Martha’s daughter Patsy

Curtis died in his arms of epilepsy in

1773 it was a crushing personal

blow. But he came personally into

half of Patsy’s substantial estate with which he was able to pay of his English debt in full and permanently—a rare feat

among the Virginia aristocracy.

It was not all

work. Washington enjoyed the amusements

of his class—fox hunting at which he

excelled and developed a reputation as the finest horseman in Virginia, entertaining

a stream of guests all the cream of

Virginia society and visitors from

other colonies and the Mother Land,

and especially social dancing at

which he was said to be quite graceful.

He also assumed the duties of a leading

squire—assuming the office of vestryman

at his local Anglican parish despite

a growing deism that detached him

from conventional and orthodox Christianity. He joined a local Free Mason Lodge not taking it terribly seriously at first but then

becoming immersed in its mysteries and rituals, the true source of

the spiritual life that he could no

longer find at the communion rail. And of course in addition to minor local

offices and honors, was elected a member of the House of Burgesses.

Given his wealth and

status, Washington could easily have become a Tory, like the Fairfax family he

had long sought to emulate. But

beginning in the mid 1760’s he began to throw his lot increasingly with those restive under the Crown and Parliament. Perhaps it was the lingering resentment of a

soldier who was never made a Regular, perhaps it was the spirit of the age. He was

never a deep or original political thinker like George Mason or a firebrand like

Patrick Henry, but he was a steady, firm political presence. The Stamp

Act of 1765 stirred him to action and became especially active after the

adoption of the Townsend Acts two

years later in which Parliament tried to re-assert

its authority over the colonies with a series of taxes, levies, and punitive actions aimed mostly at Massachusetts and New York. In response Boston merchants began to agitate for non-importation declarations by the

Colonies.

In 1769 Washington

and George Mason spearheaded the movement in Virginia where the House of

Burgesses passed a resolution

stating that Parliament had no right to

tax Virginians without their consent. Governor

Lord Botetourt dissolved the assembly

which the met at Raleigh Tavern and

adopted a boycott agreement known as

the Association. It was a critical

turning point.

The furor in the

Colonies led to the Townsend Act to be repealed in 1770 except for the tax on tea left in place as both an important revenue source and an

assertion of Parliamentary authority.

But agitation in the New World continued and in 1774 London responded

with what the Colonies called the Intolerable

Acts. Washington was livid he wrote to a friend,

They are an

Invasion of our Rights and Privileges…I think the Parliament of Great Britain

has no more right to put their hands in my pocket without my consent than I

have to put my hands into yours for money… [We must not submit to acts of

tyranny] till custom and use shall make us as tame and abject slaves, as the

blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.

Washington not only blew off steam, he acted. In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the Fairfax Resolves were adopted calling

for the convening of a Continental

Congress. The next month attended

the First Virginia Convention, and

was elected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.

Meanwhile things

were getting out of hand in Boston

where the British had closed the port to

trade, occupied the city, and quartered

troops on the town. Things blew up in April of 1775 when

Massachusetts Militiamen resisted

efforts by British Regulars to seize

armories inland. The Battles of Lexington and Concord and the Siege of Boston by Militia troops from throughout New England

followed.

When the Second Continental Congress convened in

Philadelphia the midst of the

crisis, Washington showed up in his old Virginia Blues uniform and cut a dramatic, martial figure. His life, and the fate of the colonies, would

be changed forever.

Tomorrow—Part II, First in War….

No comments:

Post a Comment