|

| S. A. Andrée, dreamer, balloonist, would-be polar explorer. |

S. A. Andrée was a smart man. A very smart man. He had big ideas. Very big.

Unfortunately his biggest idea was to try and reach the North

Geographic Pole by balloon. That

was a bad idea. A very bad idea.

On July 11, 1895 Andrée

and two companions, engineer Knut

Frænkel and photographer Nils Strindberg—a

second cousin to playwright August

Strindberg—lifted off in the balloon Örnen (The Eagle) from the

island of Danskøya (Dane’s Island) just off of the northwest coast of Spitzbergen on the Arctic

Ocean. As it rose into the air the ground

crew noted that two of the three weighed drag ropes meant to skim

the sea ice with which Andrée hoped to have some control over speed

and act as crude rudder for the otherwise free floating craft had

not been secured correctly to the gondola and dropped uselessly to the

ground. It was not a good omen. After the balloon finally disappeared from

view the intrepid explorers were never seen alive again.

Salomon August Andrée was born in the small town of Gränna, Småland, Sweden

on October 18, 1854. After the death of

his father in 1870 he completed his education at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm graduating in 1874 with a degree in mechanical engineering. He had an all consuming interest in

technology, invention, and industry believing, as many forward

thinking minds of his time did, they offered the key to the future happiness of humanity and the

elimination of hunger, want, and disease.

Although industrializing,

Sweden was a relative backwater in

Europe. Eager to see the world an

explore the exciting explosion of technological innovation that he read about,

in 1876 young Andrée sailed

to America accepting the lowly job of janitor

of the Swedish Pavilion of the Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia. He was dazzled

by the many wonders he saw there and confirmed in his faith in technological

progress. While in the States he met the

pioneering American balloonist John Wise

and read a book on prevailing

winds. Together these experiences

planted the seeds of for his ultimate adventure.

Back in Sweden he opened a machine shop and then took work as a research assistant at the Royal Institute in 1882. That was how he came to join the scientific expedition of Nils Ekholm to Spitzbergen and surrounding waters.

The Swedes, and their historic and national rivals Norway and Russia where

then in competition for Arctic exploration and possible exploitation of the

region for its fisheries and for

possible trade routes to the orient that might be open at least a

few months or weeks each year. Andrée was responsible for meteorological and

air electricity observation. This

led him to the conclusion that prevailing winds could take a balloon over, or

near the North Geographic Poll, the ultimate goal of all Polar explorers.

After

1885 Andrée worked for the Swedish Patent

Office, published frequently in scientific

journals on topic including air electricity, the conduction of heat, and reviews

of new inventions. He was well enough known and respected to

be elected to the Stockholm City Council

as a liberal reformer.

By

the early 1890’s he had fully conceptualized his plan for a polar expedition by

balloon and began testing his ideas in 1893 with the small balloon, the Svea. He made nine flights with it, starting from Gothenburg or Stockholm and travelling

a combined distance of 930 mi. In the prevailing westerly winds, the Svea flights had a tendency to carry him uncontrollably out to

the Baltic Sea and drag his basket perilously along the surface of

the water or slam it into one of the many rocky

islets in the Stockholm archipelago On one occasion he was blown clear

across the Baltic to Finland. His

longest trip was due east from Gothenburg, across the breadth of Sweden and out

over the Baltic to Gotland. Even

though he saw a lighthouse and heard

breakers off Öland, he remained

convinced that he was travelling over land and seeing lakes. H/e also tested his drag rope

breaking/steering system and believed that it gave him some control up to 10˚ variance from the wind direction, a

notion modern balloon experts describe charitably as self-delusional.

Despite

all of the red flags these experiences should have provided about his project, Andrée

considered the flights a success and began publicizing

his scheme it and raising the

necessary funds which were far

beyond his modest salary as a civil servant. He proved amazingly proficient at both and

his project drew contributions by subscription from an excited public and the distinguished endorsements of Albert

Nobel and King Oscar II—the one

on the sardine cans.

At

a lecture in 1895 to the Royal Swedish

Academy of Sciences, Andrée thrilled the audience of geographers and meteorologists. His polar exploration balloon would need to

fulfill four conditions:

- It must have enough lifting power to carry three people and all their scientific equipment, photographic equipment, provisions for four months, camping and cold weather survival gear, and ballast, totaling about 3.5 tons. It must retain the gas well enough to stay aloft for 30 days.

- The hydrogen gas must be manufactured, and the balloon filled, at the Arctic launch site

- It must retain enough gas to stay aloft for thirty days.

- It must be at least somewhat steerable.

Andrée

assured the assembled notables that he could obtain a suitable balloon from

experienced French manufactures,

that similar and even larger hydrogen balloons had remained inflated for a

year, and that existing mobile hydrogen

manufacturing units could produce the necessary at the remote departure

point. He said his drag rope system

solved the problem of steering. He must

have been convincing because all of those engineers and scientists eagerly took

him for his word.

| The balloon and gondola under construction in Paris. |

As

the money started to roll in, Andrée placed an order with balloon builder Henri Lachambre of Paris, the

most reputable and reliable of all firms.

The balloon its self was made of three layers of varnished silk 67 feet in diameter. The gondola

was built to accommodate a crew of three aloft for as long as 30 days. The sleeping

berths for the crew were fitted

at the floor of the basket, along with some of stores and provisions. Other equipment would be tied to the

exterior. Cooking would be done on a small hydrogen stove which would be lit

and burn while dangling from a rope 30 feet below the basket to prevent

accidental ignition of the highly

flammable gas.

It

is notable that with the exception of the stove and drag ropes, the whole

apparatus was old technology developed by the French a century earlier. Meanwhile developers in France, Germany, and

Britain had been working on a new generation of lighter than air craft—sausage

or cigar shaped balloons propelled by engines and completely steerable. The problem was that even with light weight

internal combustion engines

replacing earlier steam attempts;

the ships could not carry enough fuel for

a long distance flight. Count Von Zeppelin’s development of the

semi-rigid dirigible with a large envelope

containing multiple aluminum bladders of gas which multiplied

lift capacity many times over and

provided ample space within the envelope for fuel was just over the

horizon. Subsequent air Arctic and Antarctic expeditions would employ

dirigibles.

The

balloon, gondola, and hydrogen generation plant were delivered to Stockholm in

1896 in time for a flight that summer.

Literally hundreds of volunteers

clamored for a slot on the crew of what was becoming seen as a great patriotic adventure. Andrée’s first choice was Ekholt, the 48 year

old meteorologist who had headed the

1893 Spitzbergen expedition. Nils Strindberg

was the only youthful member of the team at 24 years of age. He was still a student who had achieved

notice for his original research in chemistry

and physics and who was an

expert amateur photographer and a builder of specialized photographic equipment.

The

balloon was inflated at Danskøya in July of 1896 but after days of persistent north winds the crew was force to

de-inflate the balloon and return to

Stockholm. But during the inflation

Ekholt thought he noted that the Örnen

was consistently leaking gas. Andrée

assured him that the signs of gas loss was just the constriction of the gas in the chill of the sub-arctic North. But on the voyage home Ekholt discovered in Andrée’s

logs that he had secretly been

topping off the balloon hydrogen. This

caused a falling out between the two men.

Ekholt went on to charge Andrée with reckless misrepresentation.

Back

home there was minor fall out from Ekholt’s defection and revelations, but Andrée’s

relentless public relations campaign and the patriotic fervor with which the project was now imbued in the

public mind, soon swept doubt away.

Meanwhile as international coverage increased, top French and German

balloonist with years of experience now began to ridicule the plan and label it

as near suicidal. They were particularly scornful of the drag

rope steering system. But Andrée was

literally the only Swede with any balloon experience. No one in the scientific or engineering

communities felt comfortable in challenging him openly.

| The 1897 expedition crew: G.V.E. Swedenborg (substitute), Nils Strindberg , Knute Fraenkel, and S.A. Andrée. |

To

replace Ekholt for a second attempt Andrée selected Knut Frænkel, a 27 year old recent graduate of the Royal Institute

of Technology in civil engineering. Despite his lack of background, he was

assigned Ekholt’s duties of keeping meteorological records. After the balloon was forced down his

detailed notes, including navigational observations, eventually disclosed in

detail what happened to the expedition.

He was also physically the strongest member of the crew and the only

experienced outdoorsman. After landing he became in charge of setting

up and maintaining camp sites.

Before

the Örnen left the sight of land in

the second attempt, things began to go badly quickly. Overladen by the drag of the heavy ropes, the

balloon could not achieve much altitude.

In fact it was pulled down to wave

top level, the gondola actually dipping into the water twice. The drag on the lines was so severe that two

were ripped from the craft. The crew

also hastily ejected ballast to regain height.

Within minutes it lost 1630 pounds of essential weight including 1170

lbs. of rope. That caused the balloon to

spring into the air soaring to and altitude of 2300 feet, far higher that it

was designed to fly. Already leaking,

the hydrogen expanded in the bag as the balloon rose and began to lose more gas

through an estimated 8000 pin holes.

The

wind pushed the balloon along at an alarming rate, at veering off to the north

north east meaning that even if they could stay aloft, they would never come

near the Pole. They were driven into

freezing rain, which, unlike his assurances to his Royal Academy audience, did

not simply “slip off” but began to build up, adding weight to the balloon. This, in conjunction with the continuing loss

of gas caused the craft to begin to slowly descend.

challenging

him openly.

To

replace Ekholt for a second attempt Andrée selected Knut Frænkel, a 27 year old recent graduate of the Royal Institute

of Technology in civil engineering. Despite his lack of background, he was

assigned Ekholt’s duties of keeping meteorological records. After the balloon was forced down his

detailed notes, including navigational observations, eventually disclosed in

detail what happened to the expedition.

He was also physically the strongest member of the crew and the only

experienced outdoorsman. After landing he became in charge of setting

up and maintaining camp sites.

|

| Moments before takeoff. |

Before

the Örnen left the sight of land in

the second attempt, things began to go badly quickly. Overladen by the drag of the heavy ropes, the

balloon could not achieve much altitude.

In fact it was pulled down to wave

top level, the gondola actually dipping into the water twice. The drag on the lines was so severe that two

were ripped from the craft. The crew

also hastily ejected ballast to regain height.

Within minutes it lost 1630 pounds of essential weight including 1170

lbs. of rope. That caused the balloon to

spring into the air soaring to and altitude of 2300 feet, far higher that it

was designed to fly. Already leaking,

the hydrogen expanded in the bag as the balloon rose and began to lose more gas

through an estimated 8000 pin holes.

The

wind pushed the balloon along at an alarming rate, at veering off to the north

north east meaning that even if they could stay aloft, they would never come

near the Pole. They were driven into

freezing rain, which, unlike his assurances to his Royal Academy audience, did

not simply “slip off” but began to build up, adding weight to the balloon. This, in conjunction with the continuing loss

of gas caused the craft to begin to slowly descend.

During

these hours, described in detail in Andrée’s log, he released four pigeons which had been supplied by a

Stockholm newspaper, with upbeat messages describing the flight’s

progress. Only one was found when the

hapless pigeon stopped for a rest on the mast

of a Norwegian freighter and was

promptly shot. The message in its capsule dated July 13, two days after takeoff

read, “The Andree Polar Expedition to the Aftonbladet, Stockholm. July 13

12.30pm, 82 deg. north latitude, 15 deg.5 min. east longitude. Good journey

eastwards, 10 deg. south. All goes well on board. This is the third message

sent by pigeon. Andree.”

But

all was not well. The balloon was

descending rapidly. The crew jettisoned

the remainder of their ballast and then began pitching non-essential supplies,

some of which would turn out not to be so non-essential. Free

flight had lasted only for 10 hours and 29 minutes and was followed by

another 41 hours of bumpy ride with frequent contact with the rough sea ice before

the inevitable final crash. The last few

hours they were blown far west and then east again. They had traveled about 530 air miles but

landed near 83˚ north and 30˚ east, closer to 310 miles from the take off point

in a straight line.

The

ultimate landing was relatively soft with no injuries to the crew. Even the remaining pigeons in their cages

were unhurt. All of the equipment was

unbroken. They had plenty of food. In addition strapped to a carrying ring

around the balloon was camping equipment, rifles

and ammunition, skis, snowshoes, three sleds and a boat frame that was designed to be covered by fabric salvaged from the balloon.

They were not all that far from land.

Other arctic expeditions made further treks far less well provisioned

and equipped. All in all they had

excellent chances of survival. With

better leadership, they probably would have made it back safely. Alas their leader was proving incompetent.

Totally

unfamiliar with arctic exploration, Andrée never bothered to consult any of the

veteran Swedish or Norwegians who could have explained in detail what he

need. So he brought a lot of stuff,

often the wrong stuff. To begin with their

clothing was layers of heavy woolens over

which they could wear oilcloth slickers and

their boots were not waterproof. Andrée

did not yet he also expected the sea ice to be smooth and not broken up by

channels or dotted by sun melted ice

ponds. He did not expect rain. Conditions were much wetter than he expected

and the men were wet most of the time putting them in danger of hypothermia.

Instead

of the light weight, flexible sleds

modeled after those used by the Inuit people,

Andrée had personally designed rigid

metal sleds that were both heavy and hard to maneuver over the many pressure ridges in the sea ice they

would have to cross. Each sled was

initially laden with over 440 lbs. including all of Strindberg’s heavy

photographic equipment with which he continued to document their trek.

After

spending a week organizing themselves, assembling the sleds and the boat, and

packing they set off on a march toward safety.

They had a choice of two supply depots left for them, one at Cape Flora in Franz Josef Land and one at Sjuøyane

(Seven Islands) just north of Nordaustlandet, the second largest

island in the Spitzbergen archipelago.

Their maps were faulty so Andrée almost instinctively made the

wrong choice—to head for Cape Flora which lay hundreds of miles to the east,

much further than Sjuøyane which was almost due south of their

position. From then on almost every

major decision he would make would be wrong.

Dead wrong.

|

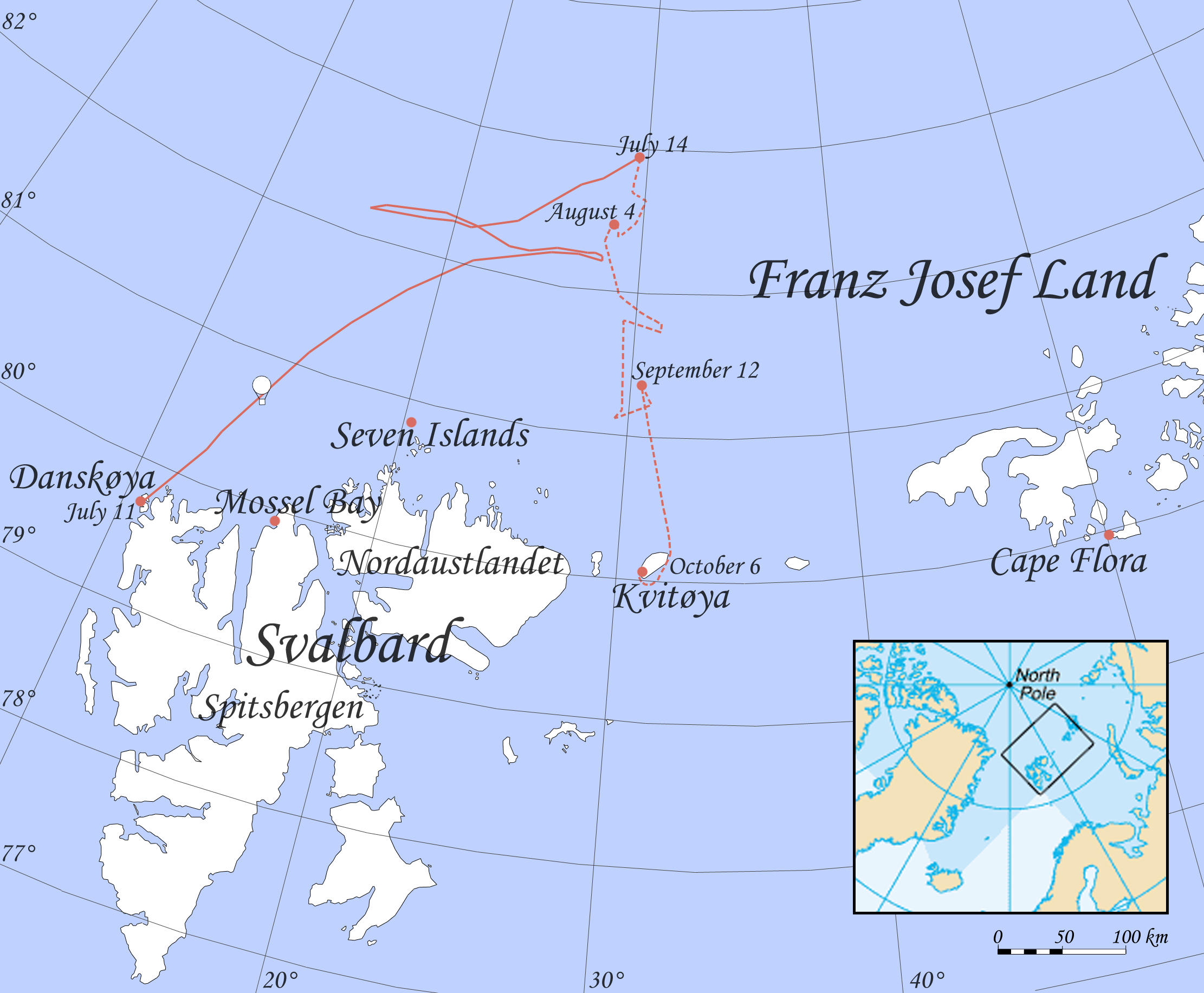

| The rout of the expedition, flight in solid red line, ice trek in dotted line. |

The

struggle to cross the sea ice was much harder than Andrée ever imagined. Ice ridges were often two stories high. Some ice

ponds were virtual lakes. Floes were separated by channels of

open water that often required all of the equipment to be unloaded from each

sled, loaded into the boat that they also had to drag with them, and floated

across only to be reassembled. Progress

was slow and painfully difficult, especially for Andrée who was the oldest and

had always lived a sedentary life. After a week and determining that they

could supply much of their food by hunting polar

bear, walrus, and seal and by fishing in the channels, they dumped much of their food—mostly

canned goods—and nonessential supplies reducing the load of each sled to

about.

That

helped. But not enough. Their forward progress was slow and the ice

was being pushed west by prevailing winds and currents. By August 4 the realized that not only would

they never reach Franz Joseph land, but that they were going backwards. They decided to turn southwest for Sjuøyane,

which should have been their objective from the beginning. The hope was that the moving ice would assist

them in this direction. At first the

terrain was just as difficult but after a few days the came on better

conditions—the smooth ice Andrée had always envisioned. Broad channels that made crossing by boat

faster than dragging the sleds. Large

ice ponds with fresh water and plenty of game.

Andrée described it as “Paradise!”

in his logs.

| |

| The explorers struggle with the boat over an ice ridge. |

Then

the wind turned again, driving them and the ice backward. Attempts to adjust their course by turning

more sharply west did not help. By

September 12 with snow beginning to fly and temperatures falling. The short Arctic summer was already coming to

an end. They realized that they would

not reach Sjuøyane. The decided to let

the ice take them where it would, hoping to get close to some hospitable

shore. A few days later they decided

that they would have to make a winter camp on the ice. Frænkel constructed them as sturdy a shelter

as he could for them to wait it out in.

The

ice began to turn south and seemed to be picking up speed. Hopes soared that it would bring them to

land. In fact it was taking them

straight to the uninhabited island of Kvitøya

east of Spitzbergen. On October 2

the ice began to pile up against the shore.

A fissure opened directly under the camp. The men scrambled to get off the ice and

transfer their gear to the islands, which took them several dangerous

hours.

But

at least they were safely ashore. Frænkel

once again constructed a cozy dwelling.

Game appeared to be plentiful. It

looked like they may be able to ride out the winter and either be found by search parties or fishermen the next spring or be able to resume the journey to

inhabited Spitzbergen.

Instead

with in day, all three were dead.

Exactly how they died is a mystery to this day. We do know that shortly after landing and

establishing camp on a high spot overlooking the ocean the entries in Andrée’s log,

which had been meticulous and detailed began a rapid descent into near gibberish. The last few pages were also damaged. We know who died first. The body of Strindberg, the youngest, wedged

into a cliff aperture by the others. Andrée

and Frænkel died together in their hut no more than a few days later.

There

are several different theories as to what killed them. The most widely sighted is trichinosis from under cooked polar bear

meet. Larvae of Trichinella spiralis were found in

parts of a polar bear carcass at the

site. Others believe it was carbon monoxide from a kerosene cooking stove that didn’t burn

its gas completely. In this theory

levels were not high enough to asphyxiate the men out right, but did brain

damage. Then a storm hit and confined Andrée

and Frænkel longer than usual asphyxiating them. Fuel was still found in the stove so for this

to have occurred the burner had to some become extinguished and the valve

closed. Wilder theories include suicide

by opium overdose or even a polar

bear attack.

Of

course none of this was learned until decades later. When the men died, folks back in Sweden did

not even realize that they were missing.

It was always expected that the outside world would lose contact with

the expedition for weeks, even months.

For all anyone in Stockholm knew, they had sailed successfully over the Pole

and had landed somewhere in the wilds of Canada

or Siberia and were attempting

to reach some settlement by overland trek.

It

wasn’t until they were gone almost a year that a search was mounted, but they had gone so far off the expected

course that no one was looking around Kvitøya.

The mystery of the crew of became a national

obsession similar to the search for Amelia

Earhart for Americans. There were

countless theories put forward, all of them wrong, plus song, poems, and novels were written.

Members

of the Norwegian Bratvaag Expedition

which was studying the glaciers and seas of the Svalbard archipelago from sealing vessel Bratvaag, found the relics of the Andrée expedition on August

5, 1930. Two crew members came ashore on the island that was usually

inaccessible because of piled up pack ice came ashore at Kvitøya to search for

fresh water and discovered scattered artifacts

including the boat with a boat hook

inscribed. “Andrée’s Polar Expedition, 1896.”

The Captain order further searches which turned up Strindberg’s and Andrée’s

skeletons, identified by markings on their clothing, and Andrée’s log.

When

the news reached Sweden, it set off an excited scramble. Stockholm reporters chartered the sealing sloop Isbjørn

which reached the island

on September 5. On this visit they found

Frænkel’s body, and a tin box

containing Strindberg’s undeveloped film,

his logbook, and maps. The ships turned

over their finds to a joint scientific

commission of the Swedish and Norwegian governments in Tromsø, Norway on September 2 and 16, respectively. The bodies of

the three explorers were transported to Stockholm, arriving on October 5.

|

| The caskets with Naval honor guard in the Stockholm funeral procession witnessed by thousands. |

The

remains were taken from the ship and transported in a solemn procession through the streets lined with tens of thousands

of Swede mourning as if the death were fresh.

At the later funeral King Gustaf

V delivered an oration. The three

explorers were cremated and their ashes interred together at the cemetery Norra begravningsplatsen in Stockholm.

For

decades they were the subject of near worshipful adoration. However recent revisionist studies have turned highly critical of Andrée and his

flawed leadership.

No comments:

Post a Comment