|

| Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein. |

Just

as Bertrand Russell, the famed British philosopher, mathematician,

historian, polymath, activist, and Nobel

Prize Winner in Literature, had

hoped the name of his pal Albert

Einstein helped attract a big crowd to the press briefing in London announcing

the latest assault on the nuclear arms

race. Einstein, the most famous scientist since Isaac Newton, had died on April 18, 1955 just days after signing

the document that the two had been collaborating on for more than a year.

Now

on July 9 of the same year the planned press

conference at Caxton Hall had to

be moved three times from a small meeting

room, to a large conference room,

and finally to the Great Hall as journalists from Great Britain and around the world flocked to hear the

announcement. By in large, it was, at

first, a hostile crowd already

writing stories with an egghead/pacifist/traitor

slant in their heads. Then the 3rd Earl Russell stepped to the microphones and began his introduction of

the Russell-Einstein Manifesto,

which had also been co-signed by nine

other world class intellectuals, all

but one of them like Einstein and Russell, were or would become Nobel Laureates.

After

his introduction Russell began:

I am bringing the warning pronounced by the signatories to the notice of

all the powerful Governments of the world in the earnest hope that they may

agree to allow their citizens to survive.

Despite all of the care and time taken to perfect the

final wording of the Manifesto, it was straight

forward and clear on its message and

call to action. The existential

threat to the survival of humanity

by the development, spread, deployment,

and likely use of the weapons of mass

destruction—the first use of that term—made their limitation and ultimate the

concern of all people and not just the belligerent

powers in possession of them. It

proposed a world conference of scientists and intellectuals of all nationalities

to be held at a neutral location to

discuss the situation and propose solutions. Invitations were extended also to all governments who were exhorted to “Remember

your humanity, and forget the rest.”

|

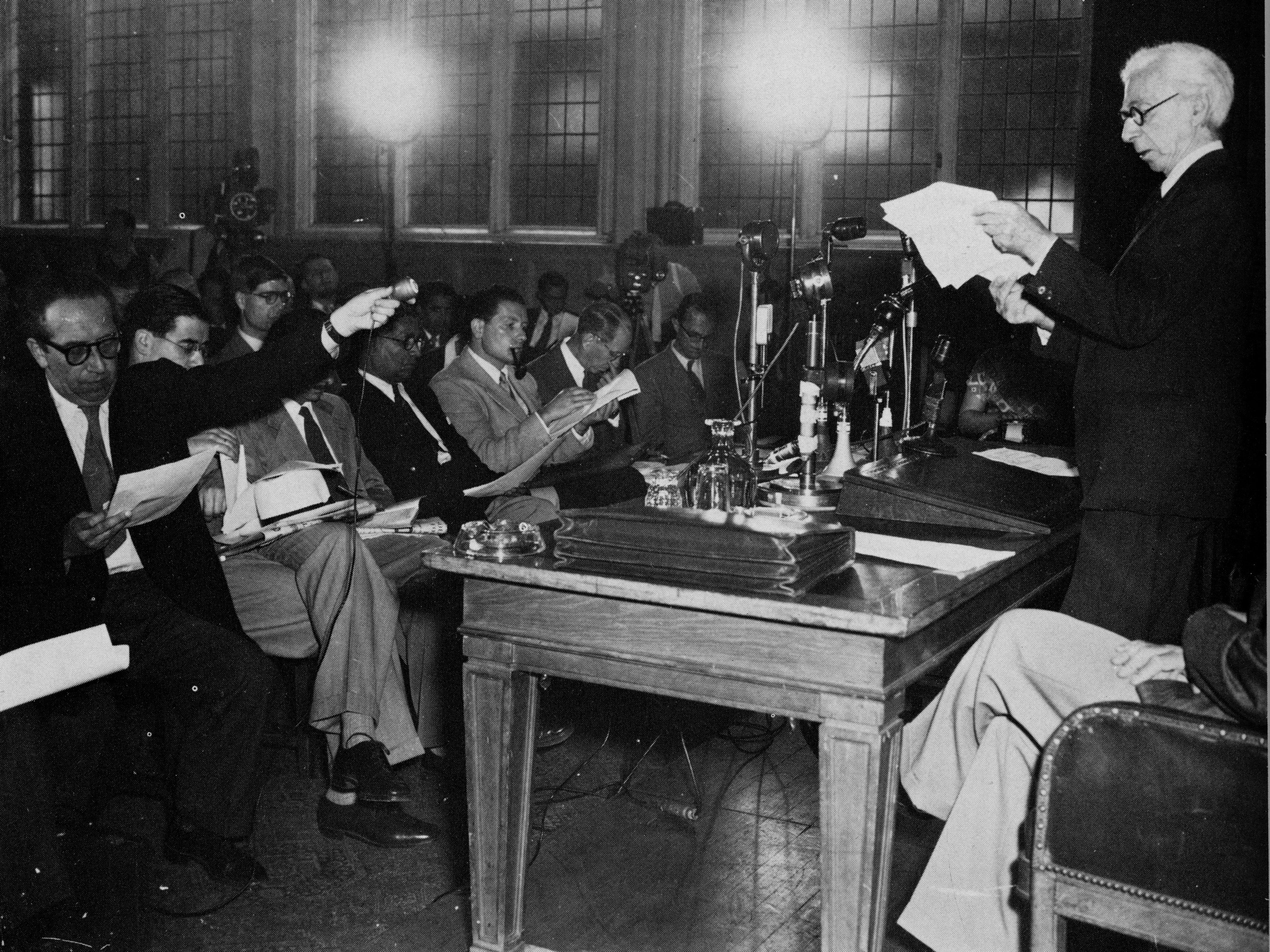

| Bertrand Russell at the press announcement for the Russell-Einstein Manifesto. |

At the end of his statement,

the early barrage of questions from

the press was quite hostile. But

Russell, noted not only for his simple eloquence

as a speaker, but for the clear lucidity

of his arguments, calmly responded and won most of the reporters over. The results were almost unanimously positive

coverage in the news columns of even

conservative and nationalistic publications.

The other distinguished signatories to the manifesto were:

Max Born—German physicist and mathematician who pioneered quantum mechanics, Nobel Prize in

Physics, 1954.

Percy Williams

Bridgman—American physicist and philosopher of

science, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1946.

Leopold Infeld—Polish/Canadian

physicist and collaborator with Einstein. The only signatory without a Nobel Prize.

Jean Frédéric

Joliot-Curie—French chemist and physicist,

former assistant to Marie Currie and

the husband of her daughter, Irène

Joliot-Curie, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1935.

Hermann Joseph

Muller—American geneticist, early expert on the

effects of radiation on organisms, Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1946.

Linus Pauling—American

chemist, biochemist,

architect, and polymath, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1954. Would go on to win second Nobel Prize—the

Peace Prize, 1962.

Cecil Frank Powell—British physicist, developer of the photographic method of studying nuclear processes, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1950.

Joseph Rotblat—Polish/British

physicist, only scientist with the Manhattan Project to develop and American atomic bomb who resigned out of conscience, specialist in the

effects of fall-out, Nobel Peace

Prize, 1995.

Hideki Yukawa—Japanese

theoretical physicist, pioneer in the theory of sub-atomic particles, Nobel Prize in

Physics, 1949.

Such a powerful brain trust, missing only the leading

scientists working on the American and Soviet

nuclear weapons programs, was hard

to ignore.

The road to

establishing the international conference was bumpy. Russell had long had a close relationship

with members of the Indian Congress

Party—he had a close working relationship with future Indian Defense Minister V. K. Krishna Menon,

the long-time head of the India League in

Britain. Menon, the architect of what

would become known as the movement of unaligned

nations as a third force in world affairs, helped secure an

invitation from Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal

Nehru to host the proposed conference in New Delhi. Such a location

would have boosted both the conference’s vaunted neutrality and India’s status

as the leader of the emerging Third

World and unaligned movement. But

the 1956 Egyptian closure of the Suez Canal and subsequent crisis in an

era when many of the European delegates would have still sailed rather than

flown to India scrubbed those plans.

The Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis,

of all people, offered to finance the conference in Morocco but suspicions about his motivation let Russell and his

associates to turn him down.

Immediately after

the original press conference Canadian

financier and philanthropist was

so enthused by the Manifesto that he offered to fund and host the conference at

his personal retreat in Pugwash, Nova

Scotia. Russell returned to that

offer after his other difficulties.

| Scientists in attendance at the first Pugwash Conferance. |

The first Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs convened in July 1957 with

22 top scientists representing 9 countries—the U.S., Soviet Union, Japan, the

United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Austria, and Poland. No national

governments sent official representatives, although the Russian, Chinese, and

Poles could not have attended without their governments’ explicit approval and

support. The relatively remote location

discouraged attendance by other noted supporters of the movement and Russell

himself was too ill to attend. His closest associate in the creation and

planning of the conference, Joseph Rotblat

was elected as Secretary General of

the on-going Pugwash Conference international organization.

The Conference

declared its main objective purpose as and methods as:

…the elimination of all weapons of mass destruction

(nuclear, chemical and biological) and of war as a social institution

to settle international disputes. To

that extent, peaceful resolution of

conflicts through dialogue and mutual understanding is an essential part of

Pugwash activities, that is particularly relevant when and where nuclear

weapons and other weapons of mass destruction are deployed or could be used…The

various Pugwash activities (general

conferences, workshops, study groups, consultations and special

projects) provide a channel of

communication between scientists, scholars, and individuals experienced in

government, diplomacy, and the military for in-depth discussion and

analysis of the problems and opportunities at the intersection of science and

world affairs. To ensure a free and frank exchange of views, conducive to the

emergence of original ideas and an effective communication between different or

antagonistic governments, countries and groups, Pugwash meetings as a rule are

held in private. This is the main modus operandi of Pugwash. In addition to

influencing governments by the transmission of the results of these discussions

and meetings, Pugwash also may seek to make an impact on the scientific community

and on public opinion through the holding of special types of meetings and

through its publications.

Although the

activities of the Pugwash Conference were not well known to the general public,

it proved quite influential in a number of ways in the turbulent and dangerous Cold War years that followed. Pugwash played a useful role in opening

communication channels during a time of otherwise-strained official and

unofficial relations. It provided background and technical work to the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, the Non-Proliferation Treaty of1968, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972,

the Biological Weapons Convention in

the same year, and the Chemical Weapons

Convention of 1993. Former US Secretary

of Defense Robert McNamara acknowledged that a backchannel Pugwash initiative

laid the groundwork for the negotiations

that ended the Vietnam War. Mikhail

Gorbachev admitted the influence of the organization on him as leader of the

Soviet Union. Pugwash was credited with being a groundbreaking and innovative transnational organization and a

leading example of the effectiveness of Track

II diplomacy.

Despite these

successes, the U.S. government frequently publicly accused the Pugwash

Conference of being a Soviet Front

organization, which it always vigorously denied. Rotblat in a 1998 Bertrand Russell Lecture said that that there were a few

participants in the conferences from the Soviet Union “who were obviously sent

to push the party line, but the

majority were genuine scientists and behaved as such.” Independent modern scholars of the movement

confirm that view.

Rotblat and the

Pugwash Conference were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in

1994. The Conference continues its work

to this day with offices in Rome, London,

Geneva, and Washington and independent, supportive Pugwash groups in more than

50 countries.

Aside from the

creation of the Pugwash Conference, the Russell-Einstein Manifesto had a significant impact on public opinion, particularly

in Britain where it, and the ongoing activities of Russell and others, inspired

the Ban the Bomb movement which

reached to status of a mass movement involving both huge demonstration and acts of civil

disobedience. Similar movements

sprang up in the United States but were constrained by the oppressive and

lingering shadow of the Red Scare from

becoming so wide-spread. But the anti-nuclear

movement proved to be an important

springboard in the mid-Sixties for

a wider American peace movement and

opposition to the Vietnam War.

Interestingly,

before the Manifesto both Einstein and Russell had complex and sometimes

contradictory histories with atomic and nuclear weapons.

Einstein

first heard from refugee scientists Leó Szilárd, Edward Teller, and Eugene

Wigner about the feasibility of an atomic weapon—something he had never previously considered—and

warnings that the Nazis were already

in the early stages of research and

development. Alarmed, Einstein wrote his

famous letter to President Franklin D.

Roosevelt in August of 1939 alerting him to the dangers. This is widely viewed as the impetus for the

creation of the Manhattan Project.

Although Einstein, a pacifist, to

no active part in the development of the Bomb, after the explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he was guilt

ridden by his role. He dedicated much of the rest of his life

to opposition to nuclear arms.

Russell was

born in 1872 into one of the most aristocratic and liberal families in

Britain. He early rose to prominence as

a mathematician and logician but was

best known to the public as a socialist—an

associate of Sydney and Beatrice Webb and George Bernard Shaw in the Fabian

Society—and as a pacifist. Unlike many British socialists and

pacifists, he did not abandon his anti-war stance during World War I.

He was a

prominent critic of the war and led demonstrations against it resulting in him

being sacked from Trinity College following his conviction under the Defense of the Realm Act. He played a prominent role in the Leeds Convention of 1917, a gathering

of thousands of anti-war socialists and radical

members of the Liberal Party. His speech to the convention drew a huge ovation and was widely reported in the

press, making him as an enemy of the state.

When he refused to pay a £100 fine under the Defense of the Realm act in

a particularly vindictive action against a scholar with significant other

assets, all of his books were seized and put up for sale. Most were bought by friends and returned to

him. Latter in the war after giving a speech

against pressure on the United States to join the war, Russell was jailed at Brixton Prison for six months during

which time he wrote one of his most important scholarly books, Introduction

to Mathematical Philosophy.

| Russell depicted in his World War I Brixton Prison. |

In 1920, despite his war time opposition to the war

Prime Minister David Lloyd George appointed

Russell to a 24 member delegation sent to the Soviet Union to

investigate the effects of the Russian Revolution.

Most of the delegates went there, like Russell, generally supportive of

the Revolutionary regime when they went.

But an hour private meeting with Vladimir

Lenin, who he found to be “impishly

cruel” and very like an arrogant “opinionated professor, Russell began to have

his doubts. Despite being carefully shepherded on a tour by Communist

functionaries, Russell carefully observed the conditions he found without preconceived notions. He noted an underlying fear in the population

almost everywhere he went and he believed loud pops he heard in the night were executions.

His companions insisted they were simply car back-fires. Of course

Russell was right. The rest of the

delegation returned with glowing reviews of the workers’ paradise. Russell

became one of the first leftist critics of the Soviet Union in the west and

wrote The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism.

When accused of being a traitor by the British left, he insisted that he

remained a socialist, but not an authoritarian.

Through the Twenties and Thirties, Russell

continued to be active in pacifist causes and in promoting disarmament. He stepped up his criticism of the Soviet

Union, particularly after the beginning of the Stalinist show trials. But

he was equally alarmed by the rise of the Nazis. He marched and spoke against both, seeing no contradiction

in it just as he marched and spoke against British brutality in India. It was all one in the same to him.

But by 1940 Russell came to the conclusion that the

Nazis were by far the greatest threat.

He reluctantly publicly abandoned absolute pacifism and gave conditional

support to the war against Germany. By

1943 he had formulated what he called Practical

Political Pacifism concluding that war is always an absolute evil but that under extreme circumstances it might be the

lesser of two evils.

When the U.S. dropped atomic weapons on Japan,

Russell immediately grasped their threat to humanity. He was also concerned with the rise of the

Soviet Union to what we would now call a super

power likely to dominate Europe. He

also saw that the U.S. and Soviet Union would quickly be drawn into irreconcilable conflict and eventually all out war. In 1946 he floated the notion that it might

be better, if war was to come, that it come while the U.S. was in sole

possession of atomic weapons. After the

Soviets inevitably developed them, any war would become a worldwide catastrophe of mutual annihilation. Critics charged that he was advocating a U.S. first strike. He insisted that he did not advocate it,

but had merely put forward his analysis of the situation and its likely

outcome. By the late Forties he had

completely distanced himself from this position.

After the

Soviets, as he predicted, tested their

first bomb in August of 1949 Russell adopted a position of demanding complete mutual nuclear disarmament and

measures to prevent other countries, including the United Kingdom from joining

the nuclear club.

Russell doggedly participated

in the growing Ban the Bomb movement, and became its most visible

spokesperson. His activities

particularly alarmed the United States which stepped up propaganda against him charging him with being pro-Communist. Given his long history of hostility to the

Soviet Union and his participations in demonstrations against the suppression

of the Hungarian Revolution and

other Eastern Block repression, the

charge was laughable.

|

| Russell and his wife Edith, center, lead the anti-nuke march that led to his second imprisonment. |

In

September 1961, at the age of 89, Russell was jailed once again in Brixton Prison for seven days after taking part in an anti-nuclear

demonstration in London. He was charged,

ironically with breach of peace. The

magistrate offered to exempt him

from jail if he pledged himself to good

behavior, to which Russell replied: “No, I won’t.”

As the

sixties wore on he became a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War. Concluding that

American action there was drifting toward genocide

in addition to his participation in street

demonstrations, in conjunction with French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre he established the Russell

Tribunal, also known as the International

War Crimes Tribunal which held

sessions in Stockholm in 1967 an ’68 concluded that the U.S. and its

allies had perpetrated a war of aggression in contravention of international

law, illegally targeted civilian populations, used weapon forbidden under

international treaty and law, abused prisoners, and committed

acts of genocide.

The Tribunal has subsequently been convened several

times to investigate cases including the Chilean Military Coup, the abuse

of psychiatry by various governments as a means of suppressing

dissent, Iraq and the Gulf War, Palestine.

Russell active in many causes right up to

his death, including opposition to what he regarded as Israeli aggression against

the Palestinians and their Arab neighbors and the Soviet suppression of Czechoslovakia.

He died of influenza at his home in Penrhyndeudraeth, Merionethshire, Wales

on February 2, 1970 at the age of 97. There

was no religious ceremony and his

ashes were scattered over the Welsh

mountains later that year.

No other public intellectual of the 20th Century or since has had such a profound influence on his times.

No comments:

Post a Comment