|

North Dakota authorities using heavy handed tactics on Water Protectors. Photo: Facebook / Sacred Stone Camp, Rob Wilson Photography. |

|

This week combined, heavily armed paramilitary forces with armored vehicles, helicopters, and sound

cannon attacked a large unarmed prayer service at a Construction site on the Dakota Pipeline. Construction workers had abandoned their equipment and fled

as Native Americans led by the Standing Rock Sioux and their allies approached the site. There were reports of teargas canisters being dropped from the helicopters. 27 were arrested in one day. It was a dramatic

escalation of the use of state power

against on-going protests which

have resulted in an unprecedented unity between

Native nations from across the U.S.A., North America, and Latin America and support from aboriginal peoples across the globe.

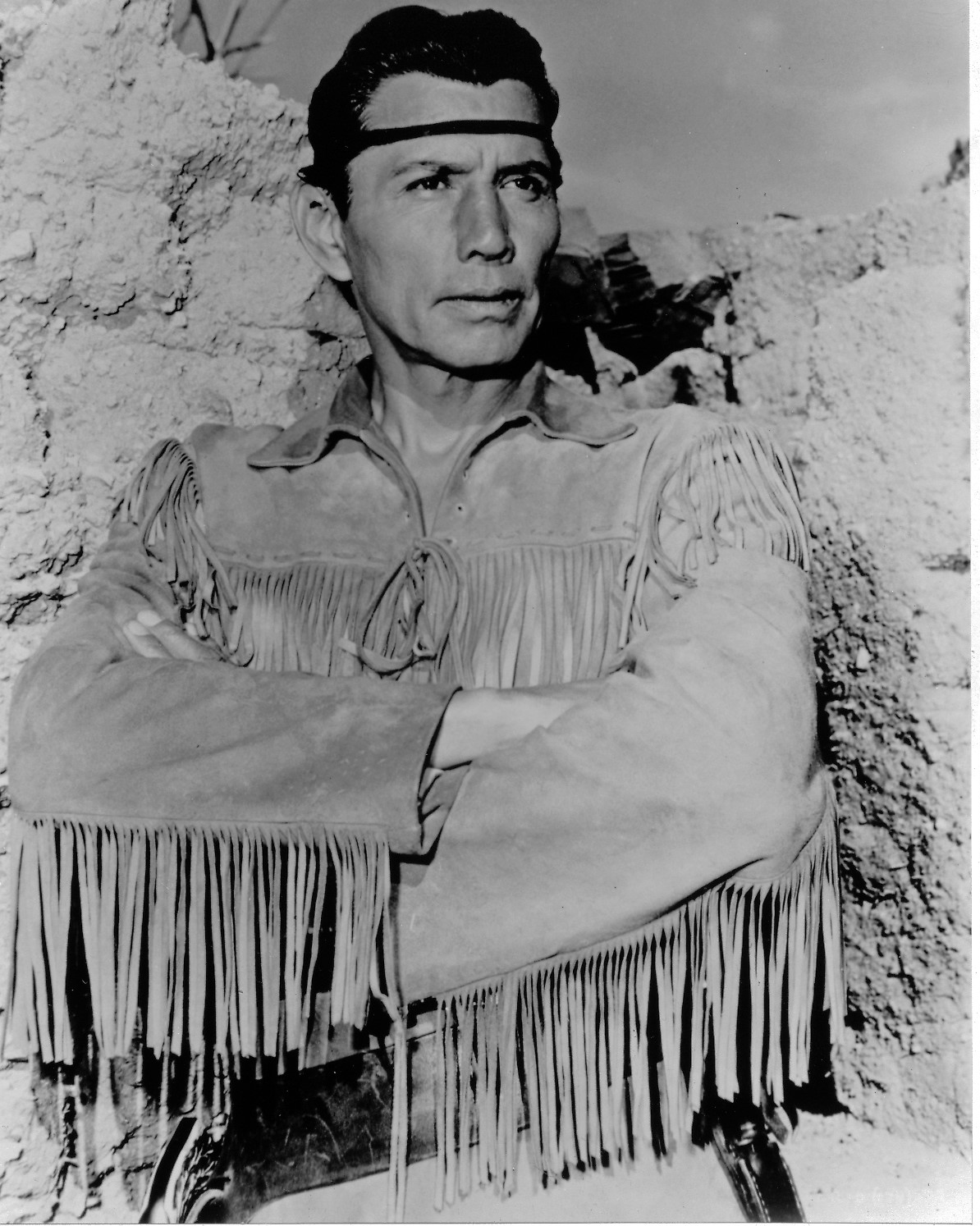

Photo by my old college pal Bill Delaney at Art Alley Gallery in Rapid City, South Dakota.

| |

|

Tonto Will Not Ride into Town for You

For The Camp of the Sacred Stone 9/30/2016

Tonto will not ride into town for you,

Kemosabe,

and

be beat to pulp by the bad guys

on

your fool’s errand.

Pocahontas will not throw her nubile,

naked body

over

your blonde locks

to

save you from her Daddy’s war club.

Squanto will not show you that neat

trick

with

the fish heads and maize

and

will watch you starve on rocky shores.

Chingachgook will save his son and

lineage

and

let you and your White women

fall

at Huron hands and be damned.

Sacajawea and her babe will not show

you the way

or

introduce you to her people,

and

leave you lost and doomed in the Shining Mountains.

Sitting Bull will not wave and parade

with your Wild West Show

nor

Geronimo pose for pictures for a dollar

in

fetid Florida far from home.

They are on strike form your folklore

and fantasy,

have

gathered with the spirits of all the ancestors

to

dance on the holy ground, the rolling prairie

where

the buffalo were as plentiful

as

the worn smooth stones of the Mnišoše,

the

mighty river that flows forever.

They are called by all the nations from

the four corners

of

the turtle back earth who have gathered here,

friends

and cousins, sworn enemies alike,

united

now like all of the ancestors

to

kill the Black Snake, save the sacred water,

the

soil where the bones of ancestors rest,

and

the endless sky where eagle, Thunderbird, and Raven turn.

Tonto has better things to do,

Kemosabe…

—Patrick

Murfin