|

| Old Blue's grave circa 1900. |

My

Mom, Ruby Irene Mills Murfin, was my

Cub Scout Den Mother—eight or nine squirrelly, squirming boys in blue shirts and caps and yellow bandanas. I was a Bear

so that made me what, eight or nine years old?

That would make it about 1957 or’58.

Mom

liked projects. Big projects.

Projects that were not necessarily in her Den Mother’s manual. Projects that helped us learn about the country around us, which happened to be the environs of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Once

she had cut up a prized possession,

an old mink coat that was out of style with its Joan Crawford shoulder pads. A furrier

could have used the pelts for a fashionable stole or evening jacket, but she gave them to

us. We made Indian war shields trimmed in fur and lances dangling pelts like trophy

scalps. We all whooped it up, terrorized

siblings and neighbor children,

and massacred settlers to our hearts content for days.

We

made all sorts of things from pine cones

she collected every summer on picnic

trips along Happy Jack Road.

|

| Ruby Murfin was going for glamor, not the Den Mother look in this photo. |

But

this day she heaved a peck basket

full of rocks she had collected from

the bed of a fast, high country trout stream that my father had fished the summer

before. They were smooth and oval or oblong

and all rough edges long ago knocked off by some old glacier and millennia of rushing icy water.

They were about the size of a good big Idaho potato. They had satisfying weight and heft in a boy’s

hand. Our minds naturally went to what we could heave them at and satisfactorily break because we were,

after all, boys which meant we were as wild

and vicious by nature as any pagan hoard.

But

before we could commit mayhem, Den

Mother Mom sat us in a circle and read to us from a picture book—Old Blue the Cow Pony by Sanford Tousey. Blue was evidently a ranch horse of extraordinary talents. Rounded up among the free and wild horses of the high

plains he was an Appaloosa, a nimble, sure footed horse preferred by the Shoshoni

and the far off Nez Percé. He

was tightly dappled. From a light

rump his coat shaded to blue-gray

in the forequarters. Some folks

called him a blue roan.

Once

broken and tamed, he took to the rigorous demands of working cattle—the

intricate dance of cutting calves or steers from a herd for branding, running at full speed over broken

ground as his rider threw his lariat, knowing just how to taut the rope so that the cowboy could leap from the

saddle and throw the critter to the

ground. He had endurance for long days and nights

of constant work and the speed to

win the Sunday afternoon races at the home

ranch.

Blue

was also extremely loyal to his cowboy. Together they rode through many seasons until the horse’s muzzle grew gray. He was the

stuff of cowboy folklore yet he kept working.

|

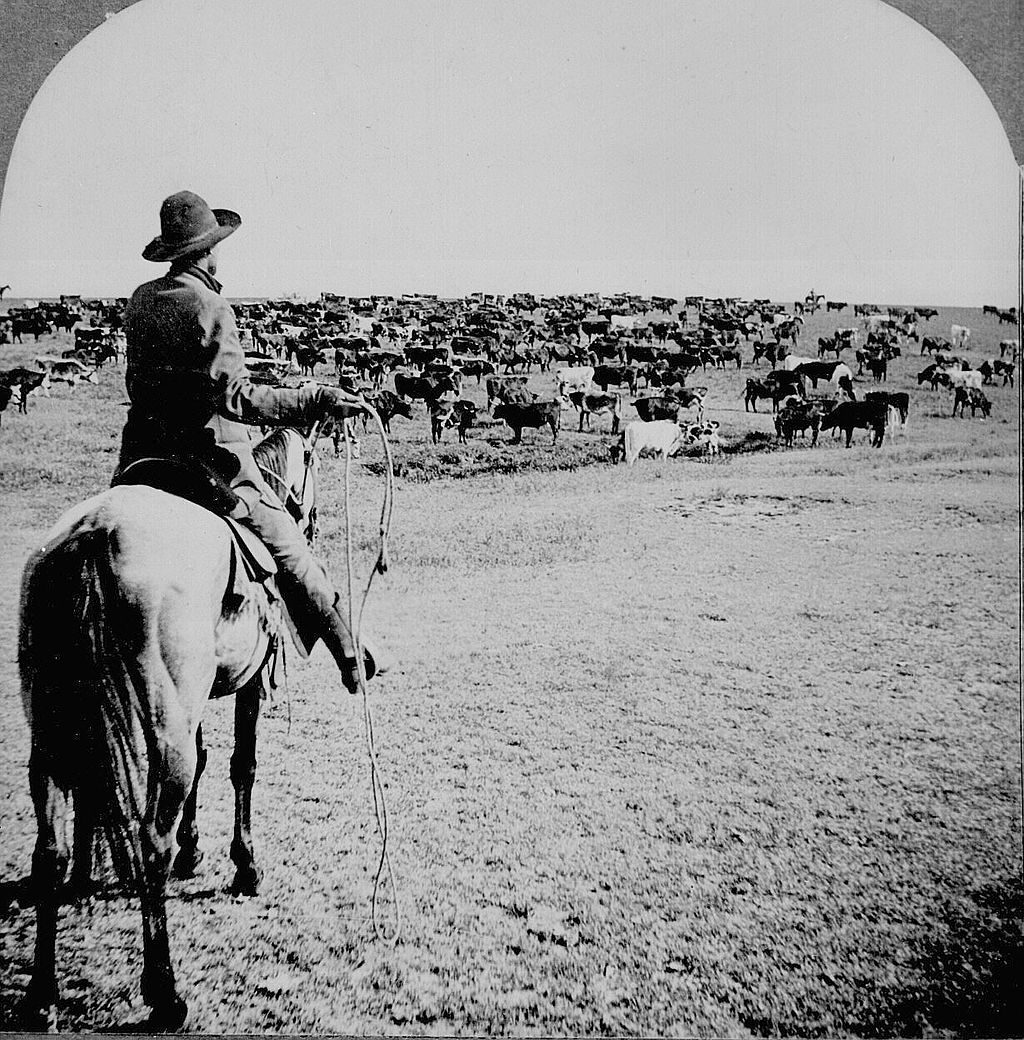

| A cowhand and his pony prepare to cut a steer from the herd. |

Then

one year—could it really have been 1886 the year of the Great Blizzard that

buried the high plains from Colorado all the way up into Canada in several feet of white death?—Blue and his rider were caught in the

high country near the Great Divide searching

for strays when the storm hit. As I recall

the tale, if they could not make it

to the safety of the home ranch, they would surely die.

Through

the raging storm with winds blowing icy pellets sideways, in

the dreaded white out the man lost all sense of direction. But Blue

knew. He kept plodding on breasting drifts up to his shoulders. Two, maybe three

days, the rider insensible and barely

clinging to the saddle. When the

storm finally broke they were in the

midst of a featureless plain far

from the Mountains.

|

| Fredrick Remington's Drifting Before the Storm captured the brutality of the Blizzar of '86 on men, horses, and cattle. |

Finally

they encountered riders from the

home ranch not more than two or three miles away. When they reached Blue he gave up his burden to them—and lay down and died.

They

had to leave him where he lay. The body

quickly froze and was covered by

drifting snow.

But

as soon as it cleared that Spring the

cowboys rode out with their shovels and

buried Blue where he lay. But now there

was a new danger…the hungry coyotes that would find the shallow grave and dig it up. So they began to haul stones from a distant stream to build a cairn

over the grave to protect it the

same as they would do for any fallen

comrade.

A small pile a

couple of feet high

would have done the trick, but they

wanted something more—a monument. They built

the pile high and fenced the plot

with split rails. And on a tall board stuck into the ground they painted, “Erected to the memory of Old

Blue, the best old cow pony that ever pulled on a rope. By the cow punchers of

the 7 X L Outfit Rest in Peace.”

When

Mom finished telling the story to us she said, “That was a long, long time ago and some of the stones on Old Blue’s grave

have fallen. But we are going to help. We are going to bring new stones!”

She

let us each pick a stone and broke out the Tempera

paints and brushes. She had us each paint our rock and decorate it with the

brands we had designed for ourselves

the week before. Mine was the P-standing-A-T, the capital letter A standing

on the top of letters P and T with a leg on each.

At

our next Den meeting Mom loaded us into my Dad’s Wyoming Travel Commission station wagon and drove out on the giant Warren Ranch. We found the grave by a rutted dirt road not far from the Colorado line. It was a raw and blustery day, the sky

leaden, but the frozen ground clear of

snow. It must have been March.

The grave was there just like in the picture but the stones slipped along the ground on one side,

the sign had faded, and the rail

fencing long since replaced with wire.

One

by one we each solemnly stepped forward and placed our stones on the pile.

Mom took some pictures with

our old Kodak Brownie Box camera. We may have said a prayer for Old Blue, or sung

a song. Or not. We piled back into the station wagon and

drove back to town in an odd silence,

not a single boy trying to start a round of Ninety-nine Bottles of Beer on

the Wall.

And

that’s the story. Make of it what you

will. There may have been miracles involved.

No comments:

Post a Comment