|

| Covers from the Seed's first three years. |

Note: I am finally getting around to continuing my

memories of the Seed and its turbulent,

After my first encounter with actual Chicago Seed staffers on a stifling hot early

summer evening in 1968 on an assignment from radical historian Staughton Lynn to seek out the Yippies, the summer rolled along

to its inevitable epic climax—the protests associated with Democratic National Convention and the resultant police

riots and armed

National Guard intervention—all of it written about and participated in by Seed staffers. I have chronicled my own

misadventures that

summer in a memoir series called Chicago Summer of

’68 that ran successively in 11 posts in this blog beginning with Chicago

Summer of ’68 Memoir—I Go to a Party on August 1, 2015.

After it was all over I returned to Shimer College in Mt. Carroll,

Illinois for what

turned out to be unexpectedly my last semester there.

For various reasons I dropped out to transfer to the very different Columbia

College in Chicago,

a communications and arts school then located on the upper floors of a commercial building fronting the Inner

Drive between Grand

Avenue and Ohio

Streets just across

from Navy Pier. I enrolled in the Story

Workshop creative

writing program run

by John Schultz, who wrote one of the best accounts of Convention week, No One Was Killed. I

had delusions of

becoming the next Great American Novelist.

I moved into my first Chicago place—a six room garden apartment

a/k/a basement—in a seedy

three flat on Howe Street west of Old Town and about a long block north of Arbitrage. It was a tough neighborhood of mixed Appalachian Whites and Puerto Ricans with whom they had a tense

and testy

relationship. I split the $78 a month rent with a black

street kid who I

connected with in a personal ad in the Seed

and a 56 year old Mexican who I had worked with at a Skokie air conditioning factory and who had lost

everything when his adult son was shot while waiting in line at a Kentucky Fried

Chicken store and

took a long, expensive time to die.

I was too stupid to realize what a red flag my roommates were to the neighborhood street

gang the Howe

Street Boys. And I represented yet another threat—the gentrification represented by Old Town

pushing west.

It turned out the Seed staff

were experiencing somewhat similar problems at their offices which were then located on Sedgewick

just south of North

Avenue which was on

the western fringes of Old Town but also in the literal shadow of the massive virtually

all Black Cabrini Green housing complex.

It was also

just a few short blocks south of my new place.

It turned out that Black gang members from the Projects did not look on the hippie

newspaper staff as friends

and allies but as White

interlopers and the nose-of-the-camel

under the tent for

White gentrification and eventual displacement of Blacks. It was no secret that the developers of Old

Town’s Carl Sandburg Village high rise apartments and others hoped to take over Cabrini Green for middle

class condos and had

support form powerful Democrats.

So the local gangs literally besieged the office, pelting it with

bricks and rocks and threatening

staffers as they

came and went. The editors issued a tone

deaf and defiant

statement in the

paper which denounced the attackers as “Black storm troopers” vowed not to “leave Old

Town until we are ready.” It turned out

that they were immediately ready and fled the offices locating them further

north and an insulating distance from Cabrini.

I stupidly planned a huge party inviting all of my old Shimer pals, folks

I knew from High School at Niles West and new acquaintances at Columbia.

Word spread and scores showed up despite the fact that I had forgotten

that the date corresponded to the first anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther

King. Cabrini Green and much of Black Chicago were rioting

just blocks

away. You could hear gunfire and see Chicago

Police cars screaming to the scene with their windows taped up for protection from rocks and bottles.

The Howe Street Boys realized that the cops had bigger fish to

fry and gathered in

front of my rowdy party. Pretty soon

guests were assaulted and I was pretty badly roughed up when I went out to try

to rescue them. I had my own personal

mini-riot. We were besieged all

night. I recounted the whole evening in

some detail in a post called April

1969—Now That Was A Party.

Like the Seed, I soon fled for digs

further north

in the first of many

moves over the next few years. It is

clear that neither the Hippie/Yippies at the Seed yet had a clear understanding of the class and racial dynamics

of the city.

That summer I joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) who I had first

encountered during the Democratic Convention.

In the time since that contact the Chicago Branch had sprung to new

life with scores of

active young members. I was astonished

to find more than 50 in attendance at my first Branch Meeting. I plunged right in to activity.

|

| The Chicago People's Park Project got some ink in the Sun Times. | | |

My first project would bring me back to the issues of urban

renewal/urban removal

that had been at the heart of the troubles on Howe Street. City demolition under the guise of slum

removal was gobbling

up block after block of

slightly rundown but serviceable working class housing, much of it in classic

brick and gray

stone two and

three flat buildings. The razing of Larabee Street from Armitage to North

Avenues just east of Howe Street had been completed while I was still

there. Middle class town homes were slated to replace a

once stable immigrant Italian and German neighborhood.

Then, leapfrogging a few blocks west, most of a block on Halsted north of Armitage was leveled. When the City announced that the land was not

going to be developed as affordable housing as originally promised but as a private

tennis club a mini-riot

broke out at a community

meeting held at

nearby Waller High School. The next day organized by the Young

Comancheros, a radicalized

Chicano and multi-ethnic

gang and the more well

known and established

Puerto Rican Young Lords hundreds of community members descended on the vacant property and began removing

rubble. Inspired by events in Berkley, California they declared that the

land had been seized by the People and a People’s Park would be built.

I had been at the Waller meeting and had a passing acquaintance with the

leaders of both the Comancheros and the Lords.

The Chicago Branch conveniently met the first night of the occupation. I reported what I had experienced at the

scene that day and they voted overwhelmingly to lend the union’s full support

to the project. I was credentialed

as official IWW liaison. I threw myself into the project with enthusiasm. After consulting with the nightly people’s

council held on the

site, I was asked to try and arrange some trucks and heavy equipment to help

with clearing the rubble which was being done by hand. They perhaps had an exaggerated idea of who

the members of our union actually were—at this point mostly now retired

veterans and young

radicals, none of

whom to my knowledge were construction workers.

None-the-less I started working the phone cold calling places out of the phone

book. I quickly discovered that there were companies glad

to haul away the rubble for construction landfill and were not particularly choosey about the perfect

legality of taking it. I was told late

they were probably mob connected and had a certain impunity that did not come from us. Then I got a guy on the line in a paving

company yard after the office staff had left for the day. He was thrilled about the project because

family members had lost their homes to urban removal. He said, “I don’t care what the company says,

I’ll be there.” The next evening after

his shift he arrived on a road grader and made short work of leveling the ground.

Needless to say the folks at the park were impressed and my Fellow

Workers were

astonished. I was too clueless to

realize that I had done anything unusual at all. After spending a few nights quasi-camping at

the park to keep the Police from seizing it when the hundreds of community

volunteers were gone, I was interviewed by reporters. They felt safer talking to me than to

scary Young Comancheros and Young Lords.

It was agreed that I would act as a press liaison for the Park. One night Studs Terkel hauled his huge, heavy

powered tape recorder and sat with several Comancheros and me around a fire as quarts of

Meisterbrau were passed

around and the young

dudes huffed typewriter solvent from brown paper bags. We

talked for two or more hours and established a relationship that would last for

years.

For the Seed the connection to

the iconic Berkley People’s Park project made our local effort especially

interesting. My first encounter with

staffers since stumbling in on a lay-out session on LaSalle Street. From then on I would encounter them at all

sorts of community events, at demonstrations, at social occasions, and at cheap

saloons like Johnny

Weiss’s on Lincoln

Avenue.

Most of August of ’69 was taken up by the People’ Park project. To our astonishment the city never

tried to deploy the Police to remove us. Plans for

the tennis club were publicly scrapped.

The community managed to put up some makeshift playground equipment,

install a few benches, and even plant some shrubs. The land was left undeveloped for more than a

decade, long after the Park had deteriorated by not being maintained. But at that moment, it was a stunning

victory.

|

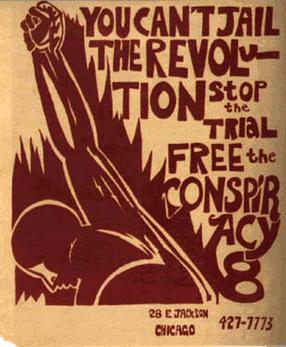

| The Conspiracy Trial riveted all of our attention. |

That fall the opening of the Conspiracy 8—soon to be Conspiracy

7—Trial on September

24 riveted all

of our attentions. The Seed, following on its deep involvement

with the Yippies and the Convention protests, made coverage of the trial a top

priority and

featuring some of its most memorable covers. Via the Underground Press Syndicate free exchange the paper’s coverage was

picked up by the radical press all over the country. There was plenty to write about—Judge

Julius Hoffman’s obvious bias, the bounding and gagging of Bobby Seals and his eventual severance from the trial, the

almost complete shutdown of the planned defense, and, of course, the antics of Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin.

The evening the trial opened I was joined by Shimer college pals Bill

Delaney, a former

Vietnam Marine, and Sarah

(Sally) MacMurrough, former

unrequited love for a March from Lincoln Park to the Federal Building in the Loop.

To our surprise

the march had only gone a few blocks when some demonstrators began to break

windows in storefronts

and attempted to overturn

some cars. For once the Chicago Police seemed taken

unaware. A kind of a rolling brawl erupted between the Cops

and the most aggressive demonstrators.

Rocks and bottles were thrown and the Police responded with tear

gas.

The three of us tried to keep our distance from the fighting, mostly by staying

on the sidewalk and maneuvering

to keep upwind of the gas. We did make it to the

Federal Building where a noisy but peaceful rally was finally held.

But clearly, something had radically changed. During the Convention protestors were mostly

peaceful and on the defense

to police and

National Guard attacks. Scuffling

was extremely limited

and occurred only after strong provocations, as when Michael James of SDS and later Rising Up Angry and friends were famously photographed trying to push

over a Police Squadrol

after phalanxes

of cops attacked the

crowd outside the Conrad Hilton on Wednesday night.

But here at least some protestors had planned to go on a rampage—many sporting

helmets.

|

| Skip Williamson stuck it to the police in his his Seed covers. |

The Flower Power era seemed dead. The Seed staff took note and although divided

on the wisdom of taking

it to the streets in

this new way, reflected it, especially in a series of memorable covers by Skip Williamson

and others.

Most of the rioters on that march were from the new RYM

(Revolutionary Youth Movement) faction that had “expelled” the far larger WSA (Worker Student Alliance)

faction—the community

organizing focused group—and the Maoist PL (Progressive Labor) factions as a summer convention in

Chicago. WSA members and the so-called libertarians—anti-authoritarian

leftists—had convened

a rump session at the IWW General Headquarters on Halstead Street during the turmoil.

Within months most campus chapters had fallen apart and RYM had split again

with the sub-faction lead by Bernadine Dorn advocating immediate armed insurrection. These were the Weathermen, noisy but widely

militant.

The Seed staff was unaffiliated

with any faction but had individuals with ties to all factions.

|

| Bring the War Home Weatherman Days of Rage poster. |

Then there were the Days of Rage that October.

The emerging Weathermen were singing I’m Dreaming of a White Riot. They planned to Bring

the War Home in

three days of demonstrations. Despite

ambitious attempts to recruit protestor nationally only about 800 hard

core showed up to battle

more than 2000

Chicago police in

full riot gear ready

to meet them. On October 8th the action started with an attempted late night

dash from Lincoln Park of the Drake Hotel at Oak Street where Conspiracy Trial Judge Julius Hoffman lived.

I was riding my bicycle home to my Lincoln Park digs from a late class at Columbia

College when I stumbled

into the melee. A guy in a motorcycle helmet and leather

jacket spotted me and yelled “If you aren’t with us, you’re against us!” and

came at me swinging a three foot two by four. I narrowly evaded him and made my escape.

The incident did not endear the Weathermen to me. The cops easily won the battle when it

reached the Drake. Six Weathermen were shot and dozens injured, some

badly but most avoided hospitals for fear of arrest.

68 were arrested.

The next day an attempt by Bernadine Dorn to lead a foray out of Grant

Park with a Women’s Militia was easily foiled. That night

Fred Hampton disassociated the Illinois Black Panther Party from Weatherman, saying, “We do not support people

who are anarchistic, opportunistic, adventuristic, and Custeristic.” That summed up my positions as well.

On the October 11 300 Weathermen pulled a surprise march

through the Loop smashing store windows and cars. Half of the rioters were quickly arrested but

Assistant States Attorney Richard Elrod broke his neck and was paralyzed when he tried to

tackle Brian

Flanagan. As a revolutionary action it was a total

failure and did not

spark any other White Riots.

The Weathermen famously doubled down, went underground and began plotting

bombing campaigns. Over the next years they

launched several attacks and on March 6, 1970 Ted Gold, Dianne Oughton, and Terry Robbins

were killed when the

bomb factory in

the Manhattan town house exploded. I had known Gould and

Oughton from the movement center for high school students I worked out of during the

Democratic Convention. They did not seem

crazy or deranged

at the time.

|

| The Seed's Fred Hampton memorial cover. |

Then in December of 1969 the assassinations of Black Panthers Fred

Hampton and Mark

Clark during a Chicago

police attack on

their apartment as they slept was a real kick in the gut.

The popular

Hampton had launched

a series of community projects including a breakfast program for children and had both hammered

out a gang

truce and forged a

new Rainbow Alliance that included the Young Lords, and the Appalachian White Young Patriots. At just 21 he was widely considered

the best and brightest star of a new multi-ethnic left movement. His death

was like a declaration of war. More white leftists, including Seed staffers were now ready to “fight

the pigs.”

In fact an obsession with the police made it seem that the revolution was a war on the pigs almost forgetting that they

were just the brutal face of greater and more powerful forces.

Tomorrow: Out of Old Town, on to

Lincoln Avenue.

Patrick, again I am amused by the parallels in our lives. I had also gone to Shimer a few years earlier than you, and also lived on Howe in a cheap apt. although in my case I lived alone or with a girlfriend.(1814 in the rear). I mostly observed all of the shenanigans during that time, didn't participate; I'm of the non-violent school. Fun to revisit through your good recall, thanks.

ReplyDelete