|

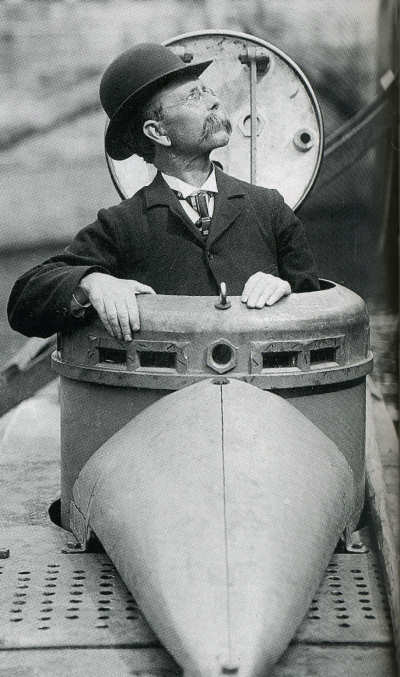

| John Philip Holland in the conning tower of one of his submarines. |

A bookish looking chap in a bowler

hat, walrus moustache, and spectacles

so Irish he had a Gaelic name—Seán

Pilib Ó hUallacháin—in

addition to his Anglicized moniker, climbed into a vessel of his own creation and sank

beneath the waters off of New Jersey. It was May 17, 1897 and John

Philip Holland successfully demonstrated

the first submarine having power to run submerged for a considerable

distance and the first to combine

electric motors for submersible

operations and a gasoline engine for surface cruising. In short he had invented the first entirely practical submarine.

Within three years the boat was snapped up by the U.S. Navy and

commissioned the USS Holland, the first of five the inventor built for the

service. The Royal Navy bought the design and launched their own HMS

Holland, the first of their Holland

class subs. The Japanese Imperial Navy was close behind building their own,

slightly larger boats based on Holland’s design. Engineers

working for the Kaiserliche Marine—Imperial German Navy—soon made

additional improvements which rapidly made the initial Holland generation of subs obsolete. A naval arms race was on and warfare at sea was forever changed.

There had been earlier attempts at underwater

craft dating back to antiquity. Legend has it that Alexander the Great was towed

by war galleys in a submersible glass vessel—a form of diving bell. The operative

word here is legend. There were

several recorded designs for various

underwater contraptions and a few actually built, with uniformly disastrous consequences in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Cornelius Jacobszoon Drebbel, a Dutchman in the service of James I of England, designed and built

the first successful submarine in

1620. It’s exact design is not

known, but several witness attest to demonstration on the Thames. The craft was some

sort of enclosed boat that was moved

by a small crew using oars. Breathable air was supplied by a process using saltpeter to create oxygen.

Despite inspiring further design work by

others that seldom left the page.

Bishop John

Wilkins of Chester was the first to

describe the use of submersible boats in naval

warfare in his Mathematical

Magick in 1648:

Tis private: a man may thus go to any coast in

the world invisibly, without discovery or prevented in his journey.

Tis safe, from the uncertainty of Tides, and the

violence of Tempests, which do never move the sea above five or six paces deep.

From Pirates and Robbers which do so infest other voyages; from ice and great

frost, which do so much endanger the passages towards the Poles.

It may be of great advantages against a Navy of

enemies, who by this may be undermined in the water and blown up.

It may be of special use for the relief of any

place besieged by water, to convey unto them invisible supplies; and so

likewise for the surprisal of any place that is accessible by water.

It may be of unspeakable benefit for submarine

experiments.

There were further experiments in France and Germany in the last decade of the 17th Century and in the first half of the 18th Century there was something of a measurable mania with more than a dozen patents granted. Few of these progressed to the stage of working models let alone vessels

capable of carrying men. But in 1747, Nathaniel

Symons patented and built the first known

working example of the use of a ballast tank for submersion. He used leather bags that could fill with water to submerge the craft. A mechanism

was used to twist the water out of the

bags and cause the boat to resurface. After

that, development stagnated until technological developments of the Industrial Age made rapid advances

possible, especially in creating reliable underwater propellant for extended

voyages and in air re-supply.

|

| David Bushells Turtle submarine |

Americans were among the

first to try and use submersibles in war operations. It did not go well. The Turtle

in 1776, was a hand-powered egg-shaped thing-a-ma-bob designed by David Bushnell, to accommodate a single man. It was the first submarine capable of independent underwater operation

and movement, and the first to use screws for propulsion. A patriot,

Bushnell built his device to attach mines

or torpedoes to the hulls British ships in New York

harbor. Apparently after several unsuccessful attempts the Turtle operated by volunteer Sgt. Ezra Lee, prepared to attack the flagship of the

blockade squadron, HMS Eagle.

She foundered and sank probably because Lee became too exhausted by the strenous effort to move the ungainly

craft through turbulent water in

the Bay.

In 1900 the French

Navy built and sailed on the Seine the Nautilus designed by American Robert Fulton. It had a sail for use on the surface and a screw

propeller powered by two men—the first known use of dual propulsion on a submarine. It proved capable of using mines

to destroy warships during demonstrations. It is considered the first truly operational

submarine. But despite his triumphs and

significant support in the Navy, Fulton could not interest the land minded Napoleon Bonaparte to buy

the boat. Undeterred, Fulton took it

across the Channel where the Royal

Navy also ultimately rejected it as well. Disappointed, Fulton returned to the U.S. where he enjoyed greater

success with the first commercially

viable river steamboat.

|

| Robert Fulton demonstrating the Nautilus for French officers in 1800 |

Further experiments continued in Latin America, Germany, and especially

France over the next decades.

The first real

application of submarines in war came during the American Civil War. The Union obtained the French designed Alligator. The promising craft was the first to

use compressed air supply and an air filtration system. It was the first submarine to carry a diver lock, which allowed a diver to plant electrically detonated mines on

enemy ships. Initially hand-powered by oars, it was converted after 6

months to a screw propeller powered by a hand

crank. She carried a crew of

20. After successful trials the Alligator

sank under tow unmanned on its

way to its first combat. A later Union

developed sub, the Intelligent Whale, was not ready for sea trials until after the war

ended. It was abandoned after 20 lost their lives in the tests.

The Confederacy,

desperate to break the blockade of

its ports, was keenly interested in

submarines. Most sank or failed

tests. The best known was the CSS H. L. Hunley, named for its designer

and chief financier, Horace Lawson Hunley. The ship carried a crew of eight including

the captain/pilot and was propelled by

a hand cranked screw. It had no air supply beyond what was sealed in the cabin giving it limited range and submersion time. A mine was

attached to a long front spar which was used to attach it to the

hull of a targeted ship. The Hunley then had to maneuver away from its target and detonate the mine at a safe distance. Essentially she was a death trap.

She lost half of her crew in one test dive. Then on February 7, 1864, the Hunley

sank the USS Housatonic

off of Charleston Harbor, the first

time a submarine successfully sank

another ship. Unfortunately in maneuvering away, she sank taking with her all

hands. In recent years the Hunley

was famously raised and restored and is on display at the Warren

Lasch Conservation Center, in the former Charleston Navy Yard.

|

| The ill-fated CSS Hunley on dock awaiting deployment. |

After the Civil War there was an international race to develop more practical and seaworthy Naval submarines.

The development of the self-propelled

torpedo in 1866 which meant that

submersables could more safely attack at a distance from the target encouraged

widespread experimentation and inovation. During the 1870s and 1880s, the basic contours of the modern submarine

began to emerge, through the

inventions of the English inventor and

curate, George Garrett, and his industrialist financier Thorsten Nordenfelt,

and a certain Irish inventor.

The 1879 Garrett Resurgam—the second he built with that name—was the first steam powered submersable and was controlled by a pair of hydroplanes

amidships. Swedish industrialist Nordenfelt built a series of warships based on incremental improvements of

Garrett’s designs and peddled them to the navies of Greece, its enemy the Ottoman

Empire, and the Russians. The Ottoman Abdül Hamid became the first sub to succesfully fire a self-propelled torpedo while submerged.

Despite these developments, submarines were

still limited in range and dangerously unreliable which is where John Philip

Holland comes in.

John Philip Holland, Jr. was born on February 21, 1841 in Liscannor, County Clare, in remote western Ireland’s Gaeltacht region. His father was a member of the British Coastguard Service who manned a

lifeboat for shipwreck rescues. His

mother, Máire Ní Scannláin (Mary Scanlon) spoke Gaelic exclusively

and English was a second language in his home.

He did not learn proper English until he was sent to St. Macreehy’s National School which by

law offered instruction only in English.

He continued his education and mastery of English in 1858 with the Christian Brothers in Ennistymon.

After completing his education,

Holland joined the Christian Brothers and was a teacher, mostly of mathematics

at several schools around Ireland. His

interest in submarines was sparked by reading press accounts of the famous ironclad duel between the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (a/ka/ Monitor)

in 1862. He recognized that the battle

had altered the future of naval warfare.

Heavily armored steam ships seemed to be nearly invincible to traditional solid

shot naval artillery ammunition and even bounced explosive rounds. He

became convinced that underwater attack would

be critical in attacking the new classes of warships which were soon rapidly

being built by world navies. He doodled and sketched and eventually submitted

a rough design proposal to the Royal Navy in hopes of getting funded. The Navy was not interested in the scribbling

of an Irish Monk.

Never a hale and hearty man, ill

health prompted him to leave the Christian Brothers in 1873 and as part of a second wave of Irish immigration from the Western counties,

came to America. At first he worked for an engineering

firm doing calculations. During this period he slipped on ice in Boston

shattering a leg. During a lengthy bed-ridden convalescence,

Holland returned to working on refinements of his submarine design. He was encouraged by Fr. Isaac Whelan, a priest who helped attend his recovery.

Holland submitted a proposal to the

U.S, Navy in 1875 but was again turned down.

Whelan may have been the connection

to a new client ready and eager to build and deploy a secret weapon—the Irish Republican Brotherhood—Fenians—which

was well financed by wealthy Irish-Americans. Always plotting, the Brotherhood hoped to use Holland’s boat to attack and

sink British shipping in Canadian waters hoping to spur a war between the U.S. and Britain that

would divert enough English might to

leave the door open to a successful rebellion in Ireland.

|

| The Fenian Ram on display with a memorial to Holland. Her capabilities piqued the interest of the U.S. Navy. |

Holland relocated to sea-side Patterson, New Jersey where he taught

at St. John’s Catholic School

for six years while he worked on designs, and built models and prototype. By 1881 the Fenians were so encouraged

that they upped their development money allowing Holland to leave teaching for

good to concentrate on building a practical ship. He completed the Fenian Ram but soon had a

falling out with the IRB leadership over disputed payments. Despite its name the Fenian Ram was armed with a clever nine-inch pneumatic gun eleven feet long, mounted along the boat’s centerline and firing forward out of her bow.

It operated like modern submarine

torpedo tubes—a watertight bow cap

was normally kept shut, allowing the six-foot-long

dynamite-filled steel projectiles to be loaded into the tube from the interior

of the submarine. The inner door

was then shut and the outer door opened. 400 psi of air

was used to shoot the projectile out

of the tube. To reload, the outer door was again shut and the water in the tube

was blown into the surrounding ballast tank by more compressed air. She could have been deadly.

But without a buyer the Fenian Ram and another improved proto-type, Holland III lay idle until 1883 when the Brotherhood

stole both boats and took them to New

Haven, Connecticut. But they had no

one who knew how to operate them.

Sheepishly, they asked Holland for help.

He understandably turned them down flat.

The Ram was put in storage but hauled out in 1916 and put on display in Madison Square Garden to raise funds

for victims of the Easter Rising. Eventually she was purchased for display

at the Patterson Museum where she

can be seen today.

But the reported capabilities of the Ram

and the Holland III finally

attracted the attention of the Navy whose encouragement

helped secure private

investment. Holland continued to

build ever better prototypes until his

1897 demonstration. The Navy purchased

and commissioned that boat as the USS Holland

in 1900.

A year earlier the Holland Torpedo Boat Company, later

reorganized as the Electric Boat Company,

was created with Holland as the chief

engineer and Isaac Leopold Rice as

President. The company got a commission to build six

more Holland class subs at the Crescent Shipyard in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

|

| The launch of the HMS Holland I at Vickers Ship Yard, October 2, 1901. |

In 1901 the Royal Navy decided to

overlook Holland’s Fenian connections and Irish Republican sympathies and

ordered a boat from him. And Holland’s

company was quite willing to oblige. A

virtual clone of the American ship,

the HMS

Holland I (or HM Submarine Torpedo Boat No 1) was built in

high secrecy at the Vickers Maxim Shipyard at Barrow-in-Furness

and entered service in 1902. She was

paired with a sister Holland boat and tender to comprise the First Submarine Flotilla. She almost saw action in 1904 when the

Flotilla was dispatched to attack Russian

ships that mistakenly sunk a

number of British fishing vessels in

the North Sea. Diplomacy diffused the crisis and the

ships were recalled before they went

into action.

HMS

Holland I, several years obsolete, was decommissioned

in 1914 and sunk under tow to the scrap

yard. She was subsequently refloated and is now on display at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum.

The Russians built a fleet of

Holland class boats under license and

as the Japanese bought 5 Holland boats which were assembled at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, the design and adapted it to longer, heavier

ships. Later with the assistance of Electric

Boat engineers they built two more, larger subs based on the Holland

model. The Russo-Japanese War of 1905 presented the occasion for the use of

the new subs in combat. The Russians assembled

7 subs at Vladivostok into the world’s

first operational submarine fleet

with the boats taking turns on 24 hour

patrols. In April the Russion sub Rom was

fired upon by Japanese surface torpedo boats but withdrew safely. The Japanese fleet never had time to deploy.

Developments by the Germans made the

Holland generation obsolete within ten years.

The U.S. Navy decommissioned the USS

Holland as early as 1905. Far more

advanced subs were engaged in World War

I in which submarines played a significant role.

|

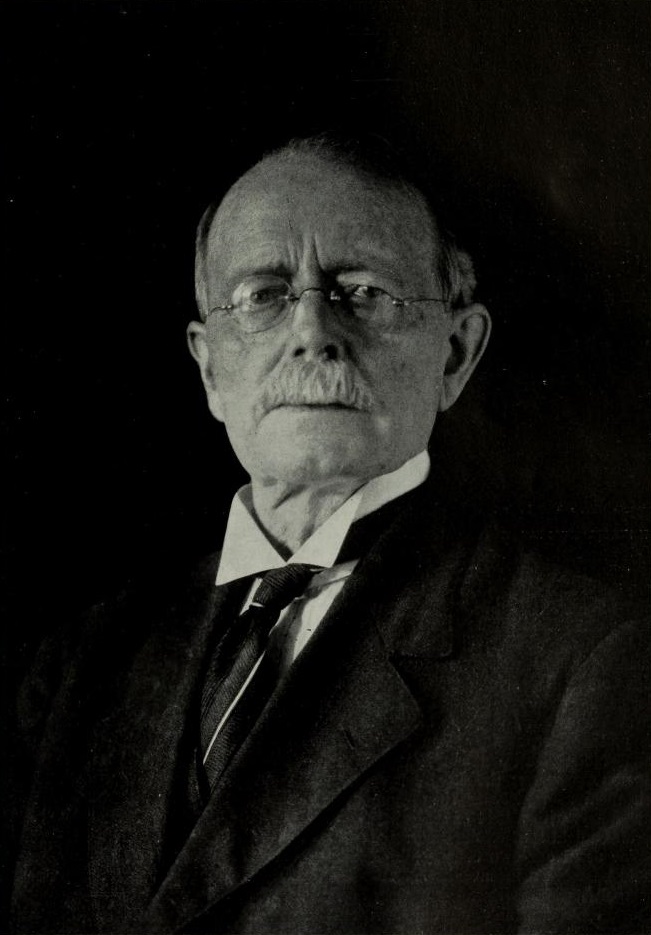

| John Philip Holland late in life. |

Holland didn’t quite live to see it.

He died on August 12, 1914 in

Newark, New Jersey at the age of

73. He worked on submarine designs for more

than fifty of those years. Not bad for a

former Monk and mild mannered school

teacher with no engineering or naval

architecture training whatsoever.

His company, Electric Boat, is now

part of the mega defense contractor

General Dynamics and continues to be the primary builder of U.S. Navy submarines.

No comments:

Post a Comment