The recently departed in shame occupant of the White House hung a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office. Old Hickory was the president that the Resident admired most because they shared so many traits. Both were vain, quarrelsome, given easily to offense, relentlessly vindictive to his enemies, autocratic while appealing to the poor, uneducated, and resentful as their champion. He was also an unapologetic racist who gloated in his Indian removal policies and defended slavery. He was also, as we will see, the sworn enemy of the just emerging labor movement. All of these “virtues” made it easy for the Cheeto-in-Charge to ignore Jackson’s opposition the Second Bank of the United States, his opposition to protective tariffs, and his swift defense of the Union in the South Carolina Nullification Crisis. But then Trump was a man of no firm convictions, only tactically useful stances. Among President Joe Biden’s first acts of cleansing was replacing the Jackson painting with a portrait founding statesman and scientist Benjamin Franklin.

Canal diggers called navvies in the jargon of the early 19th Century did physically exhausting work for long hours in wretched weather, Small wonder they rebelled.A canal connecting the navigable

waterways of Virginia with the Ohio River had been George Washington’s dream first. And a big one. Decades later it seemed that despite enormous obstacles, it was finally

coming to pass. But on January 29, 1834

the hundreds of immigrant Irish, Dutch, German laborers downed

their picks and shovels in protest to

the brutal conditions of hewing the ditch by hand from the stony soil of Virginia (now West Virginia) from first light to the descending gloaming seven days a week. Blacks

were also on the job—mostly slaves

contracted from local plantations—but whether they joined the impromptu strike is unclear.

Slave or free all were ill

clothed and given little more than a single

thin blanket in the brutal winter

weather. Wages—for those who got paid at all—were less than a dollar a day

and the use of tools and such were charged to the workers.

As the laborers downed their tools Supervisors and foremen on the job were roughed

up and some Chesapeake & Ohio

Canal Company property was damaged.

The company claimed insurrection and riot

and appealed for aid. In Washington,

DC the crusty and volatile Andrew Jackson wasted no time

in ordering Federal Troops to suppress the “rebellion.” It was the first

time the Army was ever called upon

to suppress a strike. It would not be the last.

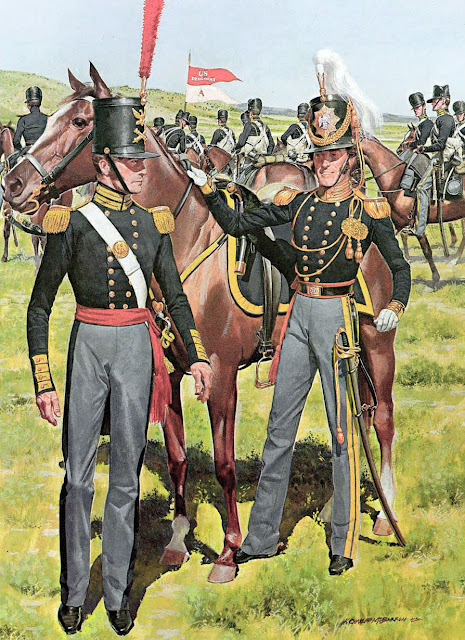

When they arrived on the scene the smartly

dressed Army Regulars had no

trouble putting down the strike by men armed

only with stones and brickbats. It is unclear

if shots were fired or if the flash of

bayonets was sufficient to disperse

the strikers, who had no organization

or union. A few identified

“leaders” were arrested, others fled. Most of the men sullenly went back to work under armed guard. It is presumed

that any slaves who participated where much more brutally handled by their owners

or overseers with the lash.

It all began before the Revolution.

Virginia planter, surveyor, and militia officer Col. George Washington had vast

land claims in the Ohio wilderness

which he dreamed of filling with settlers

on 99 year leases to the land that

he owned. But besides persistent hostility by Native American nations, and the British policy of confining legal settlement to the east of the Allegany

Mountains, the biggest obstacle to

making those dreams come true was the near geographic

impossibility of easy access to and from the land. Those mountains divided the watersheds

of the Ohio and Potomac rivers and provided a rugged

barrier to even land access.

Washington wanted to build canals,

complete with locks to raise boats to higher and higher elevations to circumvent and push past the rapids

which were the navigable limits of

the Potomac. In 1772 he received a Charter from the Colony of Virginia to

survey possible routes. But before work could progress beyond the planning stage, the Revolution intervened and Washington

was occupied elsewhere.

But he never forgot the pet project. Back home at Mount Vernon in 1785 Washington formed the Patowmack Company in. The Company built short connecting canals along the Maryland

and Virginia shorelines of Chesapeake

Bay. The lock systems at Little Falls, Maryland, and Great Falls, Virginia, were innovative in concept and construction.

Washington himself sometimes visited

construction sites and supervised

the dangerous work of removing earth

and boulders by manual labor.

Now confident that his scheme would

work, Washington began to plan more inland

sections. A call to another job—as President of the United States—interrupted his plans, but he looked forward to resuming

work in retirement.

Unfortunately that retirement did

not last long and when the great man died in 1799, the Patowmack Company

folded.

Almost 25 years later, in 1823

Virginia and Maryland planters began to fret

that the Erie Canal, which was nearing completion in Upstate New York would leave their region far behind in economic growth

as all or most of the production

from the rapidly growing states north of the Ohio would be funneled to the Great Lakes,

and via the Canal and Hudson River

to New York City. They organized and got chartered the new

Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company.

Five years later in 1828 Yankee born President John Quincy Adams, probably with some qualms about the possible effect on the

westward spread of slavery, ceremonially turned the first spade of earth.

Progress was slow and arduous as the canal ran parallel to the Potomac.

There had been other sporadic

work stoppages. Difficulties in the

era of repeated financial panics also interrupted work. Then there was bad weather, the increasingly difficult

terrain, and even a cholera epidemic. In late 1832 the ditch finally reached the

critical river port of Harpers Ferry. Workers were pushing on to Williamsport when the

trouble broke out.

Work continued with more

interruptions and a lawsuit between

the Canal Company and the Baltimore

& Ohio Railroad about a right of

way to cross from the Virginia to the Maryland side of the river also complicated matters.

In 1850 the canal finally reached Columbia, Maryland far short of the goal of connecting with

the Ohio. But by that time the rapid spread of railroads, particularly the B&O, had rendered completing the

project obsolete. Washington’s grand canal never got any

further.

But the existing ditch was still useful.

Boats, originally romantically

named gondolas and later called barges, used the water way until it finally went out of business in 1924.

Today you can visit the Chesapeake

& Ohio Canal National Historical Park and hike

along the tow path.

The bloody tradition of using Federal troops as strike breakers out lived the canal.

No comments:

Post a Comment