1968

was one of the most eventful years

in American history—the Vietnam War raged. Riots

expressing Black rage tore up inner

cities. Chicago Police themselves

rioted, beating and gassing demonstrators at the Democratic Party Convention. Martin

Luther King and Robert Kennedy were

assassinated. Richard Nixon

was elected President. Apollo astronauts first orbited the Moon.

Maybe that explains how the first shooting of students on campus by authorities on February

8, 1968 gets overlooked. But how

do you explain the fact that even then, it barely caused a ripple in the

national consciousness?

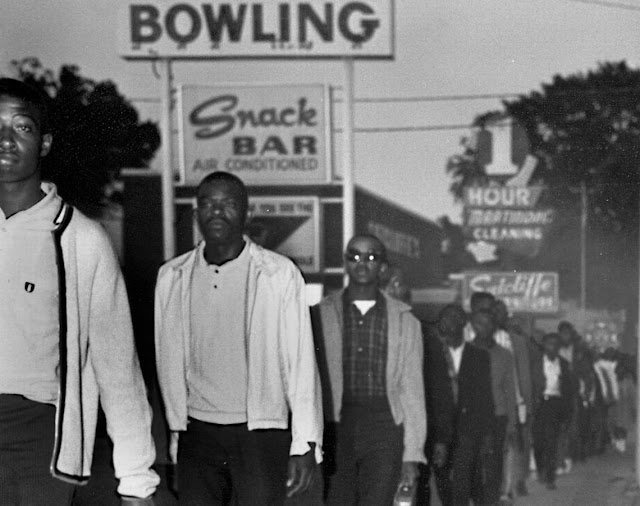

Students at historically Black South Carolina State College (SCSC) at Orangeburg just wanted to bowl. Although certainly not untouched by

more than a decade of Civil Rights

turmoil in the South, students

there, typically the first in their families to go to college, usually

concentrated on their studies. It

was certainly no hotbed of radicalism.

Like many small towns, recreational

opportunities were limited. Just

outside the University sat the town’s only bowling alley, All Star Bowling Lanes, on US 301 owned by Harry K.

Floyd. It had a firm Whites Only policy. On February 6 a large group of students

attempted to enter the bowling alley.

They were refused admission.

Scuffling broke out and local police were called. In the resultant melee nine students

and one officer were injured. Two

female students were restrained by one officer while being beaten

by another. The campus erupted in

rage.

Rowdy demonstrations and arrests

occurred the next evening. Students

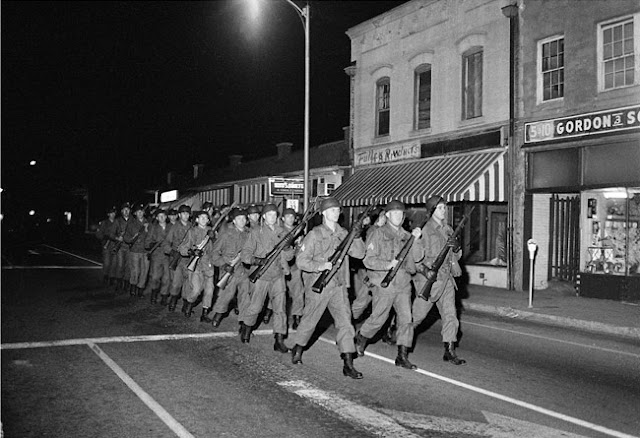

announced that they would keep up street actions. Local officials called for help. Governor

Robert E. McNair mobilized a National

Guard unit and dispatched large numbers of State Police to Orangeburg.

On the night of February 8, students

started a large bonfire in the

street near the bowling alley. Bottles

and rocks were thrown at massing authorities. There were claims that at least one Molotov cocktail was thrown. The Fire

Department was called to douse the bonfire and the State Police advanced

“in protection” of firefighters.

Students fell back to campus exchanging jeers and insults

with police and throwing objects at them.

The crowd of 200-300 students stopped just inside the entrance of

the school.

One police officer suffered minor

injuries to the face when struck by a piece of banister railing. Police later said that they came under fire

from snipers. Some witnesses recall two or three popping

sounds. Much later it was determined

that an Orangeburg city policeman

fired three warning shots into the

air with his carbine.

Unnerved and enraged the State

Police unleashed multiple volleys at

the students at a range of about 20 yards.

The Police were armed with sawed-off

riot shot guns. Ordinarily these

weapons are supposed to be loaded with light

bird shot for non-lethal crowd

control. The pump action shot guns

instead were loaded with heavy buck shot,

nine pellets to a cartridge and designed to kill.

In moments three young men lay dead. At least 26 others were shot, most in

the back while fleeing.

Many had multiple wounds from the devastating buck shot. Forty years later, another man showed a scar

and said he was shot in the stomach that night but was afraid to seek

treatment. After the shooting

stopped, two students were beaten, one for questioning the Police. Twenty-seven year old Louise Kelly Cawley was beaten and sprayed in the face with Mace while trying to bring the wounded

to medical treatment. A week later she

suffered a miscarriage as a result of her injuries.

The dead were SCSC students Samuel Hammond, 18, Henry Smith, 19 and Wilkinson High School senior Delano Middleton, 17.

That night the Associated Press (AP)

reported the shootings as a “heavy exchange of gunfire” with

authorities. It never corrected

this entirely erroneous report.

The next morning Governor McNair

told reporters it was “one of the saddest days in the history of South

Carolina.” He fretted that the state’s,

“reputation for racial harmony had been blemished.” He was also a fount of misinformation

not only backing claims that the police were fired on but claiming that the

shooting occurred off campus as students were rampaging. He also blamed “Black Power advocates” for the unrest. National news outlets did little to counter

this biased account, which became widely accepted.

The Justice Department launched an investigation. Eight of 66 State Police on the scene admitted

firing their riot guns, most of them multiple times. A ninth officer emptied the six bullets from

his .38 service revolver at fleeing students. They were indicted for “imposing summary

punishment without due process of law.” The officers were: Patrol Lieutenant Jesse Alfred Spell, 45, Sgt. Henry Morrell Addy, 37, Sgt.

Sidney C. Taylor, 43, Corporal

Joseph Howard Lanier, 32, Corporal

Norwood F. Bellamy, 50, Patrolman

First Class John William Brown, 31, Patrolman

First Class Colie Merle Metts, 36, Patrolman

Allen Jerome Russell, 24, and Patrolman

Edward H. Moore, 30. All were

white. An Orangeburg city police

officer, later promoted to Chief,

also discharged his shot gun but was never charged. Later another State Police officer, Patrolman Robert Sanders, admitted

shooting students but was never charged.

It took less than two hours for a jury

to acquit all of the officers

despite the fact that evidence presented at the trial was damming. No guns were ever found among the victims nor

did any eyewitnesses report seeing any or hearing any gunfire from the crowd.

Two and a half years after the

shooting, one man was finally convicted—Cleveland

L. Sellers, Jr. He was a young South

Carolinian who was National Program

Director for the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He happened to be in Orangeburg on February

6. He had been present at the first

disturbance outside of the bowling alley and had been injured. He was not there in his capacity with

SNCC. The organization never had a campaign

at the school, and he was not present or involved with events over the next

two days. None-the-less, state

authorities, hoping to shore up their weak case for “outside agitators,”

charged Sellers with multiple counts, including conspiracy and incitement

to riot. This was too much for even a local

trial judge, who threw out the felony counts with scathing remarks. But he did find Sellers guilty of simple

riot. Sellers spent 7 months in state

prison. In 1998 Sellers published a memoir

of his ordeal, Orangeburg Massacre: Dealing Honestly with Tragedy and Distortion.

Jack

Bass’s comprehensive 1970 account, was, despite glowing early reviews,

effectively squelched in distribution by pressure from Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) chief J. Edgar Hoover, who objected to accounts of FBI agents attempting

to cover up for the State Police.

The book was finally re-issued and became widely available by Mercer University Press in 1984.

Bass continued as an historian to

campaign for wider awareness of the buried incident.

In 2004 South Carolina Governor Mark Stafford finally issued a public

statement that, “I think it’s appropriate to tell the African-American community in South Carolina that we don’t just

regret what happened in Orangeburg 35 years ago—we apologize for it.”

The Orangeburg Massacre memorial on the grounds of South Carolina State University today.

The school is now known as South

Carolina State University. Its gymnasium

is now named in memory of the three men killed.

There is a monument on campus in their honor and the site of the

shooting is marked. The school conducts annual memorial

commemorations and promotes ongoing academic investigation of the

event.

And, oh yeah, the All Star Bowling

Lanes was renamed the All-Star Triangle

Bowl. The Floyd family still owns and operates the business. It has been integrated for many years.

No comments:

Post a Comment