A color enhanced central section of the Native American buffalo hide paintings showing the last stand of the Spanish. Historians call it a remarkably accurate depiction.

Long ago and far away two empires and their native allies clashed in the middle of nowhere and things were never quite the same again although the story of what happened was nearly lost. Sounds like the opening lines of some sword and sorcery novel or the voice-over narration of a new video game. But it really happened along the banks of a river in what is now Nebraska. The year was 1720. This is what happened.

In Santa Fe Governor Valverde of Nuevo México heard that Apaches of his province who often ranged far north and east along the western slope of the Rocky Mountains and into the Great Plains on hunting, trading, and raiding trips, were showing up with French trade goods. Under questioning, some reported trading with French voyageurs and traders along the Platte River. That was well within the territory claimed by Spain since the Conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado had searched the plains for the gold of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold called Cíbola in 1540, but far from any Spanish settlement or administrative control.

Coronado and his 1540 expedition seeking the Seven Cities of Gold explored the continental interior north of Nuevo México. The Spanish did not venture so far north again for 80 years.

The French, on the other hand, were well established in North America and continually expanding their influence through their trading and missionary dealings with native tribes. They controlled the length of the Mississippi River from New Orleans to St. Anthony’s Falls as well as the Great Lakes and claimed most of the continent east of the Father of Waters and north of Florida except for the thin strip of English settlements clinging to the East Coast. Their settlements along the River and trading stations further inland on the Missouri put them far closer to this area than his capital or outposts like Taos.

Valverde had also recently learned that Spain and France were at war in what we now call the War of the Quadruple Alliance during which France, England and most of the powers of Europe united to stop Spain from extending its influence in Italy. All of that was, of course far away and in point of fact the war was winding down—with a Spanish loss—just about the time Valverde learned about it. But, under the circumstances, he felt compelled to challenge French encroachment onto Spanish land.

The governor tapped his most important and loyal officer, Lieutenant-General Pedro de Villasur to lead an expedition to the plains to capture the French traders and reassert Spanish sovereignty. Villasur was an experienced officer but had little actual battle experience. He had spent most of his career essentially as an administrator and essentially a policeman. He had risen to be Valverde’s Lt. Governor when he was assigned the mission

Light Spanish lancers known as Cuera were the troopers who accompanied Pedro de Villasur.

Villasur assembled his expedition. He brought 40 soldiers known as Cuera, a mounted frontier force uniformed in leather and broad sombreros. In addition, he brought 60 Pueblo auxiliaries. Key to the expedition was a dozen Apache scouts. Spanish relations with the Apache were always at best delicate, but these warriors were out to seek revenge on the Pawnee who had massacred an Apache hunting party in the area the year before. The Apaches were the only ones actually familiar with the territory. Villasur also had along with him a slave, a Pawnee captured long ago by the Apache and traded to the Spanish and was then known as Francisco Sistaca to act as a translator when contact with the tribe was established.

Accompanying the expedition was a priest, Padre Fray Juan Minguez, and a civilian trader with four pack mules loaded with goods who hoped to enrich himself in the trade for furs with the local tribes once the French were disposed of.

Villasur’s chief lieutenant and commander of all of the Pueblo auxiliaries and Apache scouts was a remarkable man already so famous on the frontier that he had been granted the special title of Captain of War by the Viceroy in Mexico City. Joseph Naranjo had a Black father—probably a slave—and a Hopi mother. He was Nuevo México’s most experienced scout and had led small parties in numerous actions against various tribes who raided the haciendas of Spanish settlers. He had even been to the land along the Platte, visiting there at least three times before 1714.

On the morning of June 16, the expedition set out from Santa Fe. After reaching Taos to the north, Villasur struck northeast for the long journey to the Platte. His exact route is unknown, but it probably followed the trails used by both the Apache and Pawnee on their raids.

After an arduous journey over difficult terrain in the summer heat, Villasur finally reached the Platte in early August. It was a journey of over 700 miles and was the furthest north any Spanish military expedition had ever reached—or it turned out, would ever reach again. Near the confluence of the Platte and Loup River near what is now Columbus in eastern Nebraska they made contact with the Pawnee and their allies the Otoe. Using the slave Sistaca as a translator Villasur attempted to learn the whereabouts of any French in the area while the trader attempted to do business on his own.

The Pawnee were cool at first and relations deteriorated after that. They had probably already sent runners to their French allies alerting them to the Spanish presence. Villasur was becoming nervous as he realized that his force was outnumbered by the large number of tribesmen in the area. That nervousness increased when on the night of August 13 Sistaca slipped away from camp and disappeared—presumably to rejoin his people with ample intelligence about the Spanish force.

In 1850 American artist George Catlin depicted a Pawnee chief and two warriors in their distinctive "Mowhawk" hair styles, much the same as tribesmen would have looked almost two centuries earlier.

At dawn on August 14 a large force of Pawnee and Otoe surrounded Villasur’s main camp, bypassing another camp where the Pueblo and Apaches sleeping some distance away. Under cover of the high grass, they were able to close in on the camp undetected—Villasur had either neglected to put out pickets or they were killed. As most of the camp slept, the attack began. Survivors recalled that it started with a rattle of musketry—no firearms had been noted among the tribes, so it was assumed that fire came from the French.

Villasur and Naranjo were among the first killed. The confused survivors tried to rally in the center of the camp but were soon cut to ribbons. The only Spaniards to survive were the few Cuera minding the remuda who managed to grab some horses and flee. Meanwhile, hearing the attack from the other camp, some of the Pueblo rushed to the scene only to be cut down themselves. The others slipped away, eventually reuniting with the surviving Curea.

An educational comic book depiction of the last desperate moments.

In all Villasur and Naranjo, 34 soldiers and 11 Pueblo were killed in the battle that lasted no longer than 20 minutes.

On September 6 the survivors straggled into Santa Fe, setting off a panic about a possible French and Pawnee invasion. That never happened, but the Spanish had effectively lost a good chunk of their territory, never daring to mount another expedition to reclaim it.

We know all of this because the colonial government kept meticulous records, and because it spent the next seven years investigating the calamity and trying to fix blame. Naturally Governor Valverde took the fall and was eventually replaced.

But we also have other, even more astounding records—two buffalo hide paintings in six panels depicting the campaign and battle made by two native artists within a year of the event. The painters used the pictogram conventions of hide painting to tell a story but were also either trained in or familiar with western art as evidenced by their depictions of the combatants. Scholars believe they show a remarkably accurate depiction of the struggle—except for the presence of what appear to be French soldiers. No survivor ever reported evidence of French troops and in fact the expedition never even saw any French traders. Speculation is that Valverde may have commissioned the paintings to bolster his claims that the expedition had been defeated by French troops.

In fact, it was highly unlikely that any actual French troops were on the ground. But tough voyageurs and traders had long been as effective an agents of French ambitions as any soldiers and the gunfire at the beginning of the battle no doubt confirmed their presence with their native allies.

Now known as the Segesser Hide Paintings, they disappeared from New Mexico long ago and somehow found their way into a collection in Switzerland where they were kept for over 100 years until they were sold to the State of New Mexico in 1983. They now reside in the New Mexico History Museum. They are the earliest paintings of any military activity in North America.

A section of the Hide Paintings show French troops firing on the Spanish. No troops were there but Voyageur traders were probably the source of musket fire at the beginning of the battle.

As for the French, the traders and Pawnee brought artifacts from Villasur’s camp, including portions of his official log, to authorities in St. Louis. The French spread the word of the Spanish defeat across the tribes and took credit for it, enhancing their prestige. Soon they essentially annexed most of the former Spanish territory north of the Red River and made it part of their Louisiana province. Although they did not settle the plains, traders from St. Louis established regular ties to the tribes along the Platte and Missouri rivers and their tributaries and eventually established a handful of trading posts. They prospered mightily from the fur trade.

The Pawnee were also big winners. They came into possession of most of the expedition’s horses. Along with other stock acquired by trading and raiding, they transformed their culture. As early adopters of the Plains Indian Horse Culture, the Pawnee became, along with the Comanche the dominant power on the Southern plains and among the most feared of all warrior tribes.

For the Spanish it was the first bite out of a shrinking empire. Although they briefly regained it—and all of Louisiana—after the defeat of France in the Seven Years War in 1763—they were forced by Napoleon to give it back in 1800. He, of course, would sell it off at pennies per acre to Thomas Jefferson and the expansionist United States in 1803 to finance his wars. Weakened Spain would see one after another of her colonies lost to nationalist revolutions starting with Mexico until she was driven out of the continental Americas.

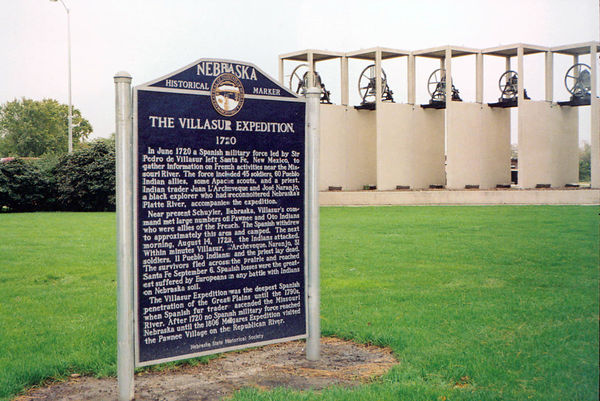

A Nebraska historical marker near the site of the battle.

After Texas asserted independence from Mexico and eventually joined the Union, the U.S. muscled its way into possession of New Mexico including what is now Arizona and parts of Colorado, Utah, and Nevada, as well as Alto California.

As for the native tribes—all of them—well they lost just about every god damn thing they had.

%20Pawnee%20Chief%20with%20Two%20Warriors%20circa%201850.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment