|

| Let's take the Pilgrim myth out of Thanksgiving. |

For

some, the annual angst over Thanksgiving is upon us. For years Native American protests that the Holiday represents European

colonialism, American racism, cultural erasure, and actual genocide have begun to register with many of the rest of the current inhabitants of this country. It is hard to deny that our First Nations, as the Canadians call their aboriginal peoples, have an excellent

point. The people we call Pilgrims represented one of the tips of the spears of a virtual invasion. Despite their reliance on the wisdom and assistance of the natives to survive their first brutal year at Plymouth and the shared harvest feast they reportedly had, in less than a generation

the settlers were engaged in brutal warfare to annihilate or displace their

former neighbors.

Growing

numbers are now joining in a boycott of

the holiday and are even joining Native American protests from Plymouth itself

to Seattle. Others, bowing to family pressure show up to dinner

armed with arguments that the whole affair is a racist travesty. Next to those who try and inflict their own brand of religion on a typically

diverse American family or bring their political

chips-on-the-shoulders to the table

these folks are the cause of an epidemic of eye-rolling, groans, and occasional full blown family drama.

As

if that weren’t enough, there seem to be no end of other reasons to hate on Thanksgiving—the ecological damage

of factory farming, the ethical

and health horrors of carnivorism,

gluttony in the face of a starving

world, wanton consumerism in the

launch of the Holiday shopping season,

and the brutal enjoyment of men hurtling themselves at each other

in a modern re-creation of the Roman

Gladiator spectacles.

Whew! And if all that wasn’t enough, we should not gloat in the embrace of our families and friends because too many are alone.

Now there is more than a kernel of truth to all of these criticisms. And there is

nothing wrong with taking time at the holiday to consider them—and to consider

how we can all do and be better.

On the other hand, there is much to admire in Thanksgiving. First, it

is, after all in its heart, a harvest

festival. Virtually every culture

that has been dependent on agriculture marked the critical completion of

the harvest, which staves off starvation

for another year, with some sort of festival. Just because we are Americans,

doesn’t mean that we don’t deserve a festival, too.

|

| A holiday shared with families of kinship and of choice |

Second, it is a feast day, something else common to most cultures. Here we

have no other national feast, accessible to all unless you count burgers and brats on the grill on

Memorial Day. Members of the many religious groups that populate our country may have their

particular feasts—Christmas and Easter, the Passover Seder, Eid

ul-Fitr, Diwali but only Thanksgiving allows us all to gather around one table.

Third, it is our national homecoming, the one day a year when families biological, adoptive, blended, or self-created come

together with all of the joy—and occasional drama—that entails. If it

wasn’t for Thanksgiving, we might never see each other except at funerals.

And finally, Thanksgiving is an occasion to express simple gratitude, surely one of

the most blest and basic of all spiritual practices. It does not require fealty to any God or any form of proscribed prayer. We are free to acknowledge that our lives are blessed in a thousand ways. We

can be grateful to a Creator, the Earth, or the laboring hands of millions who together

feed, clothe, and shelter

us. The recognition of our common debt to something larger than us

is a very good thing.

So how can we keep the good of Thanksgiving and

our consciences? Well, we can refuse to go shopping after

dinner at that Big Box Store with

the huge sale or otherwise opt in to

the orgy of consumerism. We can prepare

and serve vegetarian or vegan feast if that is our preference, or at least make sure that

everyone at the table has good food

that they are comfortable eating—and

refrain for one day from making snide or judgmental comments on the choices

of others. We can turn off the TV if the orgy of sports

offends us. We can make sure we have

made room for a homeless, forgotten, or lonely person at our tables

instead of just bemoaning their plight. They are remarkable easy to find.

But most of all, we can simply ditch the whole First Thanksgiving Myth. Because it is just that—a myth and

completely unessential to the tradition.

That meal in the fall of 1621 was not a

Thanksgiving. No one thought it was. It was meant to consume the last of the

harvest that could not be safely stored

for the starvation time of winter ahead and meat from the fall hunt that had

not been dried and smoked.

The natives probably invited

themselves to the despair of every

goodwife counting the meager larder.

At least they did bring some venison. It was not called a Thanksgiving, a religious

term usually reserved for a day of

fasting and prayer. Nor did it begin any tradition. Indeed the

whole episode was virtually forgotten within the life time of the participants.

Aside from a brief mention of the

event in an official report to English investors in the colony, which was quickly forgotten on

this side of the Atlantic, there was

no known account of the event until Governor

William Bradford’s history of

the colony written twenty years later and presumed

to be lost was re-discovered in

1854. He had a one paragraph

account of the two day feast.

We do owe New

Englanders traditions of Thanksgivings and annual post-harvest homecoming, but they were two separate and distinct things not coming

together until late 18th Century.

Their first

declared Thanksgiving Day did not occur until June of 1676 when the governing council of Charlestown, Massachusetts declared a day of Thanksgiving in gratitude for being

delivered from the threat of the Native American rebellion known as King Phillip’s War. It was not a feast day, but a day of fasting and all-day prayer. Thereafter it became more and more common for

New England towns to declare Thanksgiving days at various times of the year to

mark auspicious occasions.

It became customary to proclaim Thanksgivings at

the end of successful harvest years. The dates of these autumn events varied, but

tended to be late in the season after all crops were in, the long hunts for

venison and fowl that happened after the

first snow falls were completed, and the coastal waters became too

dangerous from storms for small fishing

vessels to set out. With all of the men home and idle and the larder at

its peak of the year, even the dour Puritans transitioned the observances into

feasts following a good long church

service.

| New Englanders made Thanksgiving the homecoming celebration, perhaps their most enduring legacy. |

The Puritans

forbade the celebration of Christmas,

which they considered corrupted by pagan practice and associated with Papist

masses, so the late season Thanksgivings became an acceptable substitute early winter

festival. As younger sons emigrated to new lands in the west of Massachusetts,

the Connecticut Valley, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont,

and Up-state New York they not only

took the custom with them, they began to try to make pilgrimages home to be with their families.

Still, Thanksgivings—days of fasting and prayer

could, and were proclaimed at any time of the year.

By the time of the American Revolution the New England custom of Thanksgivings were

well established, with a fall harvest event traditional, although celebrated at

various dates by local proclamation. In

October of 1777 New England delegates

to the Continental Congress

convinced that body to proclaim a National

Day of Thanksgiving for the victory of the Continental Army over a British

invasion force from Canada at

the Battle of Saratoga. The proclamation, a one-time event, was the first to extend any Thanksgiving

observation over the whole infant nation.

It was also a day of prayer, rather than feasting.

In 1782 Congress under the Articles of Confederation, proclaimed another Thanksgiving for the

successful conclusion of the War of

Independence. It was signed by John Hanson, as President of Congress, the man some hold up as the true first President of the United States.

Shortly after his inauguration, George Washington, the first President

under the Constitution found himself

under pressure from leaders of the established churches—the Episcopalians in the South, Quakers in Pennsylvania,

and especially the Standing Order of New

England to affirm a religious basis

for the new nation. They were

alarmed that the Constitution had omitted

any reference to God. On the other

hand the growing ranks of dissenting

sects—Baptists, Methodists, Anabaptists of various sorts, Quakers in states in which they were

a minority, and Universalists—as

well a large number of the educated

elite who were steeped in Deism

were bitterly opposed to any breach

of what Thomas Jefferson was already

calling “a wall of separation between

church and state.”

Trying to thread

the needle, Washington issued a carefully worded proclamation of National

Thanksgiving for Thursday, November 26, 1789.

He made no mention of Jesus

Christ and he only used the word God once.

Instead he called for a day of general

piety, reflection, and prayer

and invoked the broad terms of Deism—“that great

and glorious Being who is the beneficent

author of all the good that was,

that is, or that will be,” and the “great Lord

and Ruler of Nations.” Despite his

best intentions, the proclamation satisfied neither side and drew criticism

from both. Washington tried it one more

time in 1795 to even louder complaints.

Later, similar proclamations by John

Adams were met by literal riots in

the streets. After his ascension to the Presidency in the Revolution of 1800, Thomas Jefferson,

the champion of religious liberty

and separation of church and state, put an end to these exercises in public piety.

So Thanksgiving remained a regional celebration, but one which was spreading rapidly. The New

England Diaspora was rapidly spreading it throughout the North and into the

newly settled lands of Ohio and the Old Northwest Territories. The introduction of canals, turnpikes, and railroads which made transportation easier, cheaper,

quicker, and safer increased the homecomings associated with the holiday.

The South was absolutely immune to the charms of the Yankee observation and staunchly

resisted all efforts to introduce it

in their region. Christmas was their

holiday of choice and rising sectional

tensions over tariffs, western expansion, and especially slavery made the Southern aristocracy loathe to adopt any whiff

of expanding Yankee influence.

|

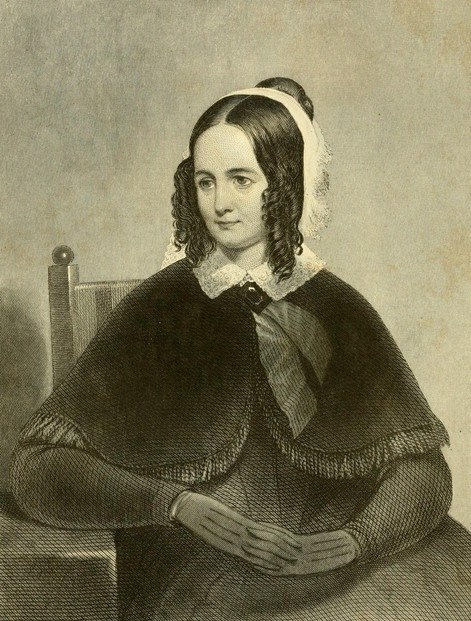

| Sarah Josepha Hale was the press agent mother of Thanksgiving and the originator of the Pilgrim First Thanksgiving myth. |

Enter Sarah

Josepha Hale, the editor of the Boston Ladies Magazine, and later Gode’s

Lady’s Book, two of the leading women’s

publications in the country, thought that whatever the protests of the

South might be, the creation of regular national Day of Thanksgiving would help

heal the nation and prevent conflict. She

inaugurated a relentless 40 year

campaign of editorials and letters to governors, Congressmen,

and Presidents promoting a national

celebration. When Governor Bradford’s

book was re-discovered and published it

was Hale who created the First

Thanksgiving myth from that one scant paragraph and tied it to the noble Pilgrims, as the Plymouth

settlers were now called, and their friendly Indian guests. It was a flawless marketing campaign and branding

that in short order convinced the public

that there was an unbroken tradition stretching back to a Pilgrim First Thanksgiving. Although the campaign won wider and wider

support and helped codify traditions

around the observance, no official action was taken until 1862.

In the midst of the Civil War another President with unorthodox religious beliefs, felt the need to unite what was left

of the shattered union. It was a bleak time. Military

disaster seemed to be the rule on every front. Agitation

for peace on terms of Southern

separation was on the increase.

|

| Lincoln's Thanksgiving proclamation. |

Abraham

Lincoln may not have been much—if any kind—of a traditional Christian. But

he believed in the hand of Providence and more than once contemplated on whether the trials

of the nation were not the just

punishments of that hand. Moreover

he needed, now more than ever, the support of the powerful Protestant clergy, who had never ceased to agitate for the

return of periodic Thanksgiving proclamations.

So it was natural that he turned to such a proclamation in the dark hour of 1862. It was that act that would nationalize the holiday permanently and

why the celebration today is more

Lincoln’s than the Pilgrims’.

Inspired by Washington’s Proclamation, Lincoln

set the last Thursday of November as

the date. He issued fresh proclamations each year of his presidency and all future Chief Executives followed suit. So did most state governors, timing their

proclamations to the Federal observance.

Eventually, if reluctantly, even Southern States had fallen into line. By the early 20th Century the emerging Fundamentalists

of the Bible Belt would become among

the most ardent supporters of the

Holiday but insisting that it be imbued with

specifically Christian trappings.

Still, for all of its wide-spread observation,

Thanksgiving was not yet an annual,

repeating national holiday. It

remained dependent on new yearly Presidential proclamations. After his election, Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the establishment of a Federal Holiday. Congress, worried about the expense of paying Federal employees for a day off of work, ignored his

plea. So Roosevelt continued to follow

precedent. But in 1939 with the nation

struggling to get out of the second dip

of the Great Depression, Roosevelt

took advantage of the five Thursdays in November that year and Proclaimed

Thanksgiving for the Fourth Thursday

instead of the last to extend the

shopping season and boost lagging

sales. He made it clear that he

intended to keep his proclamations at the second

to last Thursday through his presidency.

The change immediately became a political hot potato. Republicans

charged that FDR was desecrating the

memory of Lincoln. Preachers decried the secularizations of our ancient sacred holiday. Twenty-two states followed the President’s

lead. Most of the rest issued their

proclamations for the last Thursday. Texas, unable to decide kept both

days. The later celebration was referred

to as Republican Thanksgiving while

the earlier one was derided as Franksgiving. In 1940 and ’41 FDR stayed true to his

promise and issued proclamations for the next to last Thursday, continuing the

confusion and controversy.

In 1941 both Houses of Congress voted to create

an annual Federal Holiday on the last Thursday in November beginning in 1942

but in December the Senate changed

that to the fourth Thursday, which is usually, but not always, the last one of

the month.

By the 1950’s many employers and school districts were also giving the Friday after Thanksgiving off with

pay. The creation of a wide-spread four day weekend led to

even more long distance travel for family reunions. And soon Friday was the busiest shopping day of the year, eventually dubbed Black Friday because it was supposedly

the first day of the calendar year when most retailers finally entered

black ink.

So there you have it. Despite the ubiquitous presence of Pilgrims

and smiling Indians in school pageants

and commercials, they really don’t

have much to do with the actual tradition of Thanksgiving.

Then why not, at long last dispose of

them. Disassociate them from Thanksgiving. Suddenly our traditional harvest, homecoming,

and gratitude feast has nothing to do with colonialism and genocide. Maybe we can all sit down together in peace—at

least until drunk uncle Morrie

starts up about what a great President

Donald Trump will be.

No comments:

Post a Comment