|

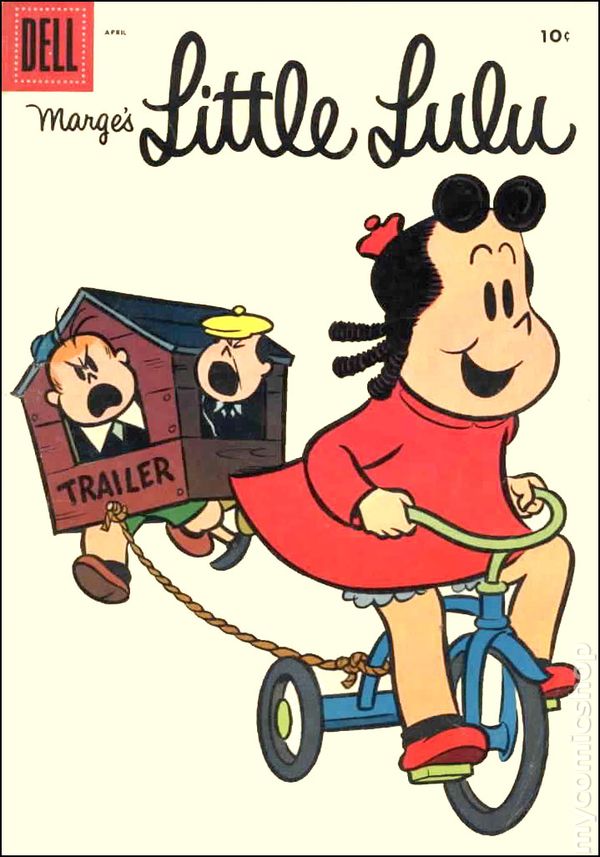

| The cover of a Marge's Little Lulu comic book. |

The

funny papers were mostly a stag club.

There had always been a handful of exceptions—Grace Drayton (Grace Gebbie),

creator of early wide-eyed apple cheeked

kid strips and the Campbell Soup

Kids; Rose O’Neil of the Kewpies and

later a Greenwich Village bohemian

feminist; and Ethel Hays and Gladys Parker who did flapper strips in the Roaring Twenties. Later Dale Messick would become a sort of super star herself with Brenda Starr Reporter. That would open the door just enough for Cathy Guisewite to chronicle a new

generation of angst filled single working women, Lynn

Johnston to bring new realism and poignancy to the domestic family strip, and for a yet new generation elbowing their way into an increasingly competitive newspaper market.

One

woman had early roots in the ‘20’s, created an iconic

character in the ‘30’s and craftily

oversaw the development of the character as lucrative brand even after she

stopped doing most of the drawing herself.

Yet the woman who signed her work simply as Marge and whose creation would spawn the Friends of Lulu, an organization

that promotes women in comics, was

the opposite of the flashy, self-promoting Messick.

Marjorie Henderson Buell was shy and reclusive. Using only her nick name helped mask her identity.

When her creation, Little Lulu became one of the most

popular strips in the country spawning comic

books, commercial endorsement deals,

and animated cartoons for theatrical release and television, she shunned requests for interviews and tried to avoid having her photograph published. She had a largely conventional marriage

and raised three children in middle

class suburban normalcy. Despite the

fact that spunky Lulu was famous for trying to break down the doors of the boys-only club house, it is unclear if

Buell ever considered herself a feminist.

Marjorie Lyman Henderson was born on

December 11, 1904 in Philadelphia. He protective

mother kept her and her two sisters at

home, overseeing tutoring until she

was 11 years old. Her mother also kept

her in 19th Century sausage curls long

after they had gone out of fashion. All three girls were instructed in art and showed real talent.

At

age 16 she had her first cartoon published locally in the Philadelphia Public

Ledger. She was soon

successfully peddling single panel

cartoons to humor magazines like

Judge

and Life as well as general

interest publications like Collier’s

and the Saturday Evening Post . By

the late ‘20’s she was signing these contributions simply as Marge.

A

major break came when her mentor Ruth

Plumly Thompson, who had taken over as author of the Oz books following the death of L.

Frank Baum, asked Henderson to illustrate

her book, King Kojo and some of her magazine short stories.

The

Boyfriend became

her first syndicated newspaper

strip. It featured a teenage girl

protagonist and was seen by some as female

answer to the popular Harold Teen strip. The feature was only marginally successful

and ran only in 1925 and ’26. Meanwhile

another comic with a female lead, the single panel Dashing Dot found a home

in magazines.

|

| The first Little Lulu mute single panel comic in the Saturday Evening Post in 1935. |

In

1934 the Saturday Evening Post asked

her to create a replacement for Carl Anderson’s Henry which was going

into syndication as a daily newspaper strip. Henry was mute single panel

about the misadventures of a boy about 9 years old. The Post

wanted another child

character. Marge gave them a girl. In a rare interview she later explained, “a

girl could get away with more fresh stunts that in a boy would seem boorish.”

Little Lulu began its weekly installments in the Post in the

February 23, 1935 issue. Lulu was hardly

recognizable from her late form except for the sausage ling curls from Marge’s

own childhood. Like Henry, it was mute early in its run.

Eventually

Lulu did speak—quite sassily—she also developed a supporting cast, most

importantly a chubby pal Joe who

would later be renamed Tubby.

Just

as the popularity of Little Lulu was taking off, Marge

married Clarence Addison Buell, a

wealthy Bell Telephone executive. The two took up residence in the upscale Philadelphia suburb of Malvern. The couple agreed

that Clarence would turn down job

promotions that would require that

they move. Marge would work mostly

from home and limit her activity so that she could devote time to her husband

and two sons, Larry born in 1939 and

Fred born in 1942.

| A rare photo of Marjorie Henderson Buell with her oldest son, Larry. |

That

agreement limited continuing outside work as an illustrator or initiating new

projects. But Marge, a shrewd businesswoman, turned her

attention to marketing Lulu and maximizing revenues from her. She insisted on maintaining the copyright

for Little

Lulu in her own name instead of signing it over the Curtis Publishing, owners of the Post as was common. That gave her complete control over the character.

In

1939 she licensed a Little Lulu doll made by the Knickerbocker Toy Company.

Not only did these become a hot

item in department store toy

departments, but the Post and Ladies

Home Journal gave tens of thousands away as a premium for taking out two

year subscriptions.

| A copy of a lobby card poster for the Little Lulu cartoon shorts of the 1940's. The title of the most recent release would be printed in the lower white box. |

Beginning

in 1943 Famous Studios produced 28 animated theatrical shorts for Paramount Studios that entertained

audiences until 1947 when Buell demanded a more lucrative deal. Paramount

replaced her with a red-headed clone Little Audrey.

In

1944 Buell sighed a deal for Lulu to become the mascot of Kleenex brand

tissues. She appeared in print ads, on billboards, in store

displays, her voice was heard on the radio,

and eventually she showed up on Television

on programs like the Perry Como Show which was sponsored by the tissues. From 1952 to 1965 the Lulu even appeared in an

elaborate animated billboard in Times Square in New York designed by Artkraft

Strauss. The ad campaign was a success and made Kleenex the dominant brand of tissue in America,

so widely used that its name became generic. It also made Buell a very wealthy woman.

| An early version of the changing animated electric billboard featuring Lulu for Kleenex in Times Square for thirteen years. |

Beginning

during World War II, the first print

ads were properly patriotic. The company bragged in the press that, “the

little curly-haired girl in red spends her time reminding Americans to conserve

to support the war effort.” Despite this

patriotic twist the Saturday Evening Post

was unhappy to see its most popular

cartoon feature used in product

endorsements, but since Buell retained the copyright there was nothing the

magazine could do to stop it. Pressure

brought on Buell led to strained relations.

The Post published its last Little Lulu panel in its December 30,

1944 issue.

Buell

retired from personally illustrating Little

Lulu thereafter, except for the lucrative Kleenex campaign. But she maintained tight control over design

and content of subsequent projects. And

there were many of them as Buell turned her attention to aggressively marketing

her prize character.

First

was entering the burgeoning comic book

industry. Buell signed a deal with Western Publishing in 1947 which made

Lulu the lead story in 10 issues of the Dell

Four Color comic book and

then began a long run in her own magazine under the name Marge’s Little Lulu. The comic was written and illustrated

by John Stanley under Buell’s loose

direction. The comic continued under the

Dell, Gold Key, and Whitman labels until Western Publishing

exited the comic book business in 1984 with issue #268. Tubby got his own comic that also ran for

several years. In addition there were numerous

special editions, giants, book compellations, and eventually reprints. Artist Irving Trip and others took over for

Stanley after he retired.

The

comic book kept Lulu in the public eye and Buell aggressively marketed products

featuring her including greeting cards,

balloons, toys, bean bags, towels, and children’s apparel.

In

1950 the Chicago Tribune–New York News

Syndicate began syndicated a daily

four-panel strip and a Sunday color

strip. It was marketed as a competitor to Ernie Bushmiller’s quirky and popular Nancy. Buell took a more hands on approach to the

strip in the early days than she did with the comic book. She wrote some of the scripts and even

produced some roughs. Woody

Kimbrell was the initial artist followed by Roger Armstrong in 1964 and Ed

Nofziger from 1966 until the strip was canceled in 1969.

Buell

resisted pleas by the artists and even her two sons to introduce Black and other minority characters

like other popular kid strips, notably Peanuts had done. She was at heart deeply conservative and conventional

and her own suburban experience had been virtually completely free of any

regular contact with minorities except as maids

and servants.

After

the end of the daily strip and given the changing tastes of the country, Buell

retired in 1971 and finally sold her rights to Lulu to Western Publishing.

After

the death of her husband she lived in Ohio

near or with her son Larry. She died

on May 30, 1993 at the age of 88 of lymphoma

in Elyria, Ohio.

Larry

became a professor of American Literature at Harvard, and her son Fred a professor

of English at Queens College.

Lulu

comics and comic books have been translated

and reprinted in dozens of languages around the world. In addition to most major European languages she has appeared in Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, Japanese, Hebrew, Indonesian, Korean, Thai, Turkish, Ukrainian, and Vietnamese.

Lulu

lived on in various guises even after the comic books stopped publication. There were two half hour live action ABC Weekend Specials in the early ‘70’s. Japan’s

Nippon Productions produced two seasons of Little Lulu and Her Little Friends which ran in ABC’s Saturday

morning cartoon block in 1975 and ’76.

Canada’s CINAR

produced a new series for HBO, The

Little Lulu Show from 1995 to ’99 with Tracy Ulman voicing Lulu in the first season. These shows are still in reruns on Canadian TV.

| The odd Brazilian spin-off with Lulu and her friends as teens. |

Perhaps

the oddest appearance was Luluzinha

Teen e sua Turma (Little Lulu Teen and her Gang) a Brazilian

comic book in the Japanese manga style

that portrayed Lulu and her friends as teenagers. The series ran for 65 issues between 2005

and earlier this year.

In

2006, Buell’s family donated the Marge

Papers to Harvard’s Schlesinger

Library including a collection

of fan mail, comic books, scrapbooks, original art, and a complete set of the newspaper strips.

But perhaps the most Marge’s most significant legacy

was the Friends of Lulu founded by Trina Robbins and other women

artists and figures in the world of comic books and comic strips in 1994 at a comics convention. In 1997 the first annual Lulu conference and Lulu

Awards were held in California. The organization also sponsors an amateur press association that fosters

the fanzines where many women get

their start in the comics industry, and

has published a number of books including How

to Get Girls (Into Your Store), a guide for comics shop owners

on how to make their stores more female-friendly; Broad Appeal, an anthology of

comics by women artists; and The Girls'

Guide to Guys’ Stuff featuring over 50 female cartoonists.

Unfortunately

the Friends of Lulu ran afoul of IRS

regulations for non-profits and

had its tax-exempt status revoked

leading to the organization being formally

dissolved in 2011. Former members

and supporter still gather at comics conventions, especially Comic-Con International in San Diego where they present a play

based on a script from a Little Lulu comic

book every year.

No comments:

Post a Comment