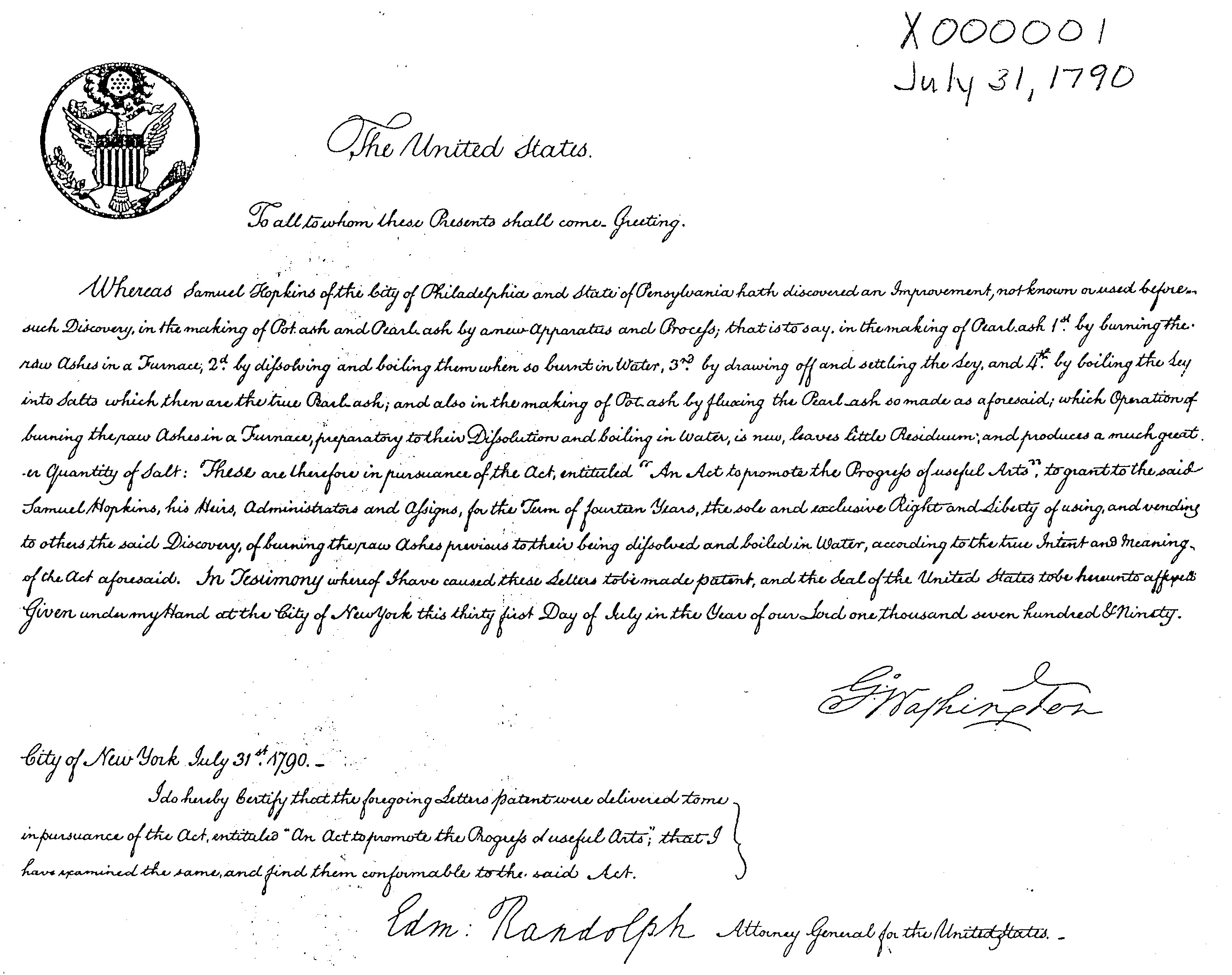

|

| This Battle of the Crater souvenir post card was sold for decades around the Virginia battle field. For all I know glossy print versions may still be available. Like many depictions of the battle it show a valiant Confederate charge into the Yanks trapped in the crater. It also minimizes the number of Black troops--only two are identifiable in this picture--despite the fact that they suffered virtual annihilation. How history gets both the valient Lost Cause veneer and is white washed. |

File this one in the The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang

aft agley Department. The plan was brilliant. Its execution

nearly perfect down to the last detail.

The result exactly as desired,

until mere mortal men marched into the

breach.

By the summer of 1864 the grim carnage of the American Civil War had ground to a stalemate. Since Gettysburg

a year earlier Confederate General

Robert E. Lee and his legendary Army of Northern Virginia had been hard pressed by vastly superior Union forces of the Army of the Potomac under the command of Major General George Meade directly and

personally supervised by Commanding

General Ulysses S Grant.

Once famous for his audacious and aggressive maneuvers, Lee was forced to defend the Confederate capital of

Richmond. He erected

impressive earthen work

fortifications in a wide ring around

the city. The old man was proving to

be just as adept at what would be

the future of war in the Industrial Age—trench warfare.

|

| Lee digs in to defend his capital. A war of maneuver settles into seine, stalemate, and trench warfare. The breastworks of the Confederate Fort Mahone on the Peterburg line. |

The key to Richmond was at the rail

hub of Petersburg through which

the city and the army could remain

supplied with food, supplies, and munitions. Grant called it the “backdoor to Richmond” and proceeded to lay siege to the city and its fortifications.

The armies faced each other along a 20 mile front from the old Cold Harbor battlefield near Richmond to areas south of Petersburg. An

attempt to take the town by assault ended in failure on June 15. Since

then the two armies had pounded each other with artillery, peppered the opposing lines with deadly fire from sharpshooters and snipers, and delicately

probed each other’s lines with reconnaissance

patrols. Both commanding generals

were frustrated.

|

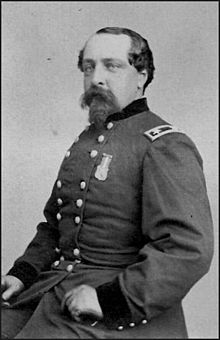

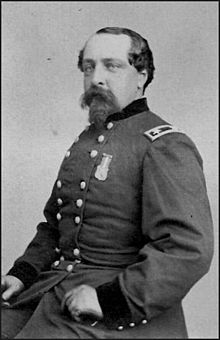

| Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry had an idea and commanded the perfect troops to make it happen. |

It took a mining engineer to come up with a solution to Grant’s problem—Lt.

Col. Henry Pleasants, commanding the 48th

Pennsylvania Infantry of Maj. Gen.

Ambrose E. Burnside’s IX Corps. His proposal

was simple on paper—dig a long

mineshaft from the Union siege

trenches then under Confederate

outer defenses until under the major

fortification at the center of the Rebel lines, Elliott’s Salient. Sappers would

then plant and set off a huge mine

which would blow the fort away and open a breach through which Union forces could pour, smashing the Confederate I Corps and

rolling up Petersburg before Lee could

muster his forces from elsewhere along the lines.

Burnside was a once promising commander nursing a badly bruised reputation.

His indecision as Army of the

Potomac commander at Fredericksburg in

December of 1862 had thrown away the

best chance for an early end to the war and led to one of the bloodiest defeats the Army was ever handed. Busted

back to a Corps commander, his lack of aggressiveness at Spotsylvania Court House earlier that

year had aggravated Grant. Burnside was determined to prove that he was imaginative and aggressive. He quickly gave the go-ahead to Pleasant’s plan. Up the

chain of command Meade and Grant also signed

off on it but were not much

convinced it would work. Neither lent much logistical support to the effort.

|

| A successful and proven Division commander, Major General Ambrose Burnside had been elevated to quickly to command of the Army of the Potomac after Lincoln finally got fed up with George McClellan. His indecision at Fredricksburg led to one of the Army's worst defeats. Demoted to a Corps commander, he was blamed for over caution st Spotsylvania Court House. Now he was an officer desperate to salvage his reputation. |

Pleasants’ own troops, tough coal miners from the fields of western Pennsylvania, were just the men for the job. They were maybe the only men in the Union

army who would not consider the task

drudgery. In fact for them digging in the soft Virginia soil must have

seemed like a cakewalk.

Digging began in June and proceeded

quickly. The men had to scrounge lumber to shore up the tunnel and for the ingenious ventilation system which sucked fresh air from the narrow mine entrance all the way to the face of the digging via a wooden duct. Fetid

air at the end was heated by a

constantly burning pit fire and vented

out drawing the fresh air to fill the vacuum. This system avoided the use of multiple air vents which could have been observed.

The miners dug by hand and removed the

soil in wooden soap and ammunition

boxes drawn by rope along a crude wooden plank rail. On July 17 the shaft

reached under Elliott’s Salient at a depth of about fifty feet. A perpendicular

gallery about 75 feet long extended

in both directions.

All of this had been accomplished un-detected by the enemy. Confederate

intelligence reported rumors of the

mine to Lee about two weeks after construction began. He

didn’t believe it. Finally after

receiving new report he began desultory anti-mine efforts which failed to find or detect the shaft.

Confederate General John Pegram in charge

of the artillery in the sector took the rumors more seriously,

however, and on his own authority as

a precaution had trenches and gun

emplacements built to the rear of the Salient as a secondary line of defense.

Meade and Grant finally decided to go all in on the plan. The gallery underneath the Confederate

position was filled with 8,000 pounds of

gunpowder in 320 kegs. The main chamber was extended to 20 feet below the fort and was packed shut with 11 feet of earth in the side galleries and 32 feet of packed earth in the main gallery

to prevent the explosion blasting out

the mouth of the mine.

|

| The miners' handiwork--the Union tunnel with the point of detonation of tons of explosive under the Confederate strong point. |

On July 27 Grant sent Major Generals Winfield Scott Hancock and

Phil Sheridan on a combined infantry/cavalry attack along

the James River southwest of

Richmond and miles from the Petersburg front.

In what became known as the First

Battle of Deep Bottom or New Market

Road the forces were repelled in two

sharp days of skirmishing around Fussell’s

Mill and Bailey’s Creek. Although

Grant held out some hope that

Hancock’s infantry could punch a hole in

the defenses to allow Sheridan’s cavalry to pour into Richmond, or failing

that ride around the city severing rail

connections, he was not entirely

disappointed when the attacks were repulsed. They had succeeded in causing Lee to send troops from Petersburg to re-enforce the line along the James.

Grant turned his personal attention to the well-developed plans for the Petersburg

mine attack.

|

| Brevet Brigadier General Edward Ferrero, a famed New York dancing master in civilian life and a veteran of several campaigns, commanded the division of U.S. Colored Troops at Petersburg. He and his men were tapped to lead the assault after the mine blew up and underwent two weeks of special training. At the last minute they were replaced in the order of battle by a white division for political reasons. |

Weeks earlier at an officer’s call Burnside had acceded to the plea of former New York City dance master Brigadier

General Edward Ferrero to use his division

of United States Colored Troops

(USCT) as the leading assault unit.

Burnside, who originally had other plans, agreed. The division was fresh, well equipped, and most importantly at full strength, 4,200—a

rarity when veteran units were often whittled away to half their original size

or less through combat loss, disease, and desertion. The division was given a rarity for the Civil War—two full

weeks of specialized training and instructions for this mission. After the mine went off, they were to move

ahead in the confusion of the enemy and secure the crest of the crater on either side to allow the rest of the Corps to pass along the rim or

through the crater itself.

When Meade reviewed the plans he fretted

that the unit which Burnside considered fresh was simply green and therefore unreliable in combat, especially in a critical role. He also worried that if the Colored Troops failed, they would discourage commanders from accepting and

fighting alongside of others.

Although Colored Troops had proved

themselves in other theaters, they were new to the elite Army of the Potomac. Grant agreed and ordered Burnside to revise the order of battle less than 24 hours

before the attack.

At another officer’s call Burnside

conducted a lottery among his three white divisions to select a lead. Brigadier

General James F. Ledlie of the 1st

Division won the draw. The Colored

Division would join the two others in the second

wave of the attack.

Ledlie returned to his unit but never issued the special instructions

for taking the flanking rim first. The men were told only that they would have

the honor of leading a full frontal

assault.

Meanwhile Col. Pleasants was deep

underground personally supervising the

final placement of the explosives and making sure the earthen plugs in the

tunnel were strong.

The mine was supposed to be detonated at 3:30 in the morning of June 30. But the Army had provided inferior

fuses. Two attempts to light it failed.

Finally two volunteers crawled

into the mine, found where the fuse had burned out had broken, and spliced a fresh fuse on the end. It was

after dawn when the mine finally blew up at 4:30, with enough light for Confederate pickets to recognize that there were large Union forces inside their lines.

The explosion itself went off flawlessly. And impressively. The fortifications of Elliott’s Salient were blown sky high killing most of the garrison. Despite a little warning, the Confederate line was thrown into the

anticipated confusion and panic.

Ledlie’s men at first seemed as stunned

by the spectacle as the enemy. They paused to take in the scene and had to

be prodded forward by their officers and

sergeants. Ledlie himself was nowhere to be found. He was well to the rear, completely out of line of sight of the battle in a bombproof bunker with Ferrero of the

Colored Division. Passing a bottle between them the two officers were getting quietly drunk.

|

| The untrained and leaderless men of the 1st Division charged into the crater instead of taking the rim as planned. They were trapped. The Turkey shoot commenced. |

When the 1st Division reached the

crater instead of securing the rim,

they charged directly into it. And at

the bottom they stopped to gape the destruction. The delays

allowed time for Brig. Gen. William

Mahone to cobble together a

Confederate force to rush to plug

the breech. They quickly occupied the vacant rim and commenced a

Turkey shoot of the defenseless men in the Crater. Troops madly

tried to scramble up the sides, but found the dirt gave way under them.

They were trapped.

|

| Burnside ordered the Colored Division forward to reinforce the 1st. They also pushed into the Crater and were trapped. They were singled out by enraged Confederates and were nearly annihilated. No prisoners were taken from them. The wounded were shot or bayoneted. Only a handful escaped, mostly men who did not enter the crater. |

But they were not to be alone. Burnside, refusing to be charged once again with

indecision and lack of aggression, ordered the Colored Division forward to reinforce the trapped 1st. Denied the rim, they followed into the Crater.

Their appearance enraged the

Confederates who intensified fire, including volley after volley of intense artillery fire.

The Turkey shoot continued for more than two hours. At one point some troops supporting troops did manage to flank the crater and advance

inside the Confederate line taking

trenches in brutal hand to hand combat. But there were not enough of them and could

not be reinforced. After holding out

for a short while they were cleaned out

of the trenches by a counter attack.

As the battle wound down, Confederate troops summarily

executed Black soldiers trying to surrender. Fearing

retaliation by the Rebels, some White Union troops bayonetted Blacks as well.

The Colored Division was virtually

wiped out as an effective unit.

In all Union forces suffered 3,798

casualties including 504 killed, 1,881 wounded, and 1,413 missing or

captured. The Confederates lost

1,491—361 killed, 727 wounded, and 403 missing or captured.

|

| The Crater after the battle. |

Probably the best chance of the year at an early end to the war was thrown away. Grant reported to Army Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck, “It was the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war…Such

an opportunity for carrying fortifications I have never seen and do not expect

again to have.”

The finger pointing and blaming began immediately. A Court

of Inquiry pinned the rap on Burnside, who was relieved of command and never

entrusted with another. His reputation was ruined beyond repair. All of his division commanders were censured, especially Ledlie and Ferrero.

One of the few to come out of the

affair with an enhanced reputation

was Pleasants, whose troops were not

engaged in the actual fighting that day.

He was rewarded for his plan and execution with a brevet to Brigadier General.

At war’s end in 1865 the Congressional Joint Committee on the

Conduct of the War opened an inquiry into the debacle. Pleasants testified that if Burnside had been allowed to retain his original order of Battle, that the operation

would have been a success. Grant concurred. He wrote to the Commission:

General Burnside wanted to put his colored division in

front, and I believe if he had done so it would have been a success. Still I

agreed with General Meade as to his objections to that plan. General Meade said

that if we put the colored troops in front (we had only one division) and it

should prove a failure, it would then be said and very properly, that we were

shoving these people ahead to get killed because we did not care anything about

them. But that could not be said if we put white troops in front.

In the end, the commission agreed, laying

the blame at Meade’s feet and exonerating Burnside. Little good did that do for the generals

already destroyed reputation.

On the Confederate side Mahone was hailed a hero and became one of Lee’s most trusted division commanders in the

last year of the war.

The Siege of Petersburg ground on for months more into a new

year. Union successes elsewhere, especially William Tecumseh Sherman’s operations in the Deep South, were sealing the fate of the

Confederacy. After Grant’s bloody Wilderness Campaign offensive, Lee was finally forced out of his trenches.

Richmond fell. Lee surrendered. The South

was defeated.

But had the operation at the Crater

gone as planned, maybe a million lives

might have been saved.