On

July 27, 1816 two United States Navy gun

boats opened fire on a small but modern and professionally

constructed fort on the Apalachicola

River near the Gulf of Mexico. After wasting

a few rounds to find range one of the boats fired a round

of hot shot which landed within the

walls of the fort on the powder magazine

resulting in a thundering explosion that

completely destroyed the fort and killed almost all of the 300 defenders, their families, and refugees inside. That round has been variously called the deadliest

cannon shot ever fired by the Navy or by any U.S. armed force. Perhaps, although it is likely that one of the huge

explosive shells fired from the naval

rifles of the great 20th Century battle

ships was at least as deadly but

in the heat of multiple salvo battles we may never know. Suffice it to say it was a hell of a blast.

But

you, the alert history reader, may

well wonder: just who the United States was at war with in 1816, a year and a

half after the end of the War of 1812? The answer

is…no one. The

new nation was theoretically at peace with the world. And therein lies the tale.

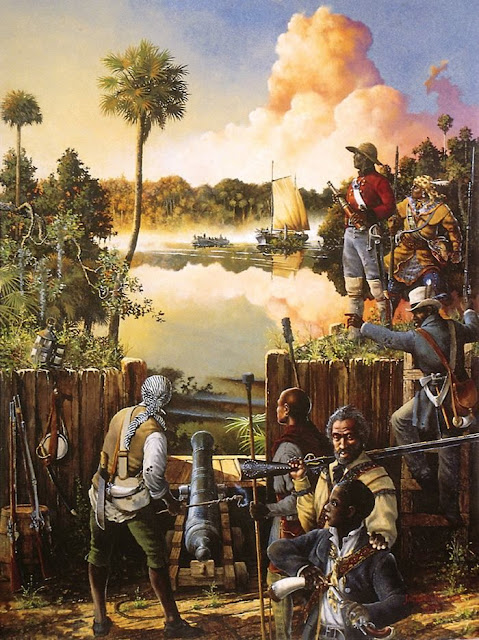

Perhaps

it will make more sense to you if I say that those holding the fort

were an unofficial but trained Black militia, recently escaped slaves from both Spanish Florida and plantations in southern Georgia, and a few dozen Native Americans under a Choctaw chief whose name has been lost to history. Those

natives were from the people becoming

known as the Seminole, a tribe or nation in the making consisting of members of small Florida tribes persecuted

by the Spanish, and elements of the Creek

and Choctaw who fled to Spanish

territories after the defeat of the Red

Stick Creek by General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. Those Black refugee slaves were also becoming assimilated into the new,

still very informally organized tribe.

When

you understand the target, it is clear why no declaration

of war was necessary to be as aggressive a commander as Andy

Jackson.

The

Spanish had mostly abandoned the Florida panhandle militarily, although

not their sovereign claim to it,

after Jackson’s American Army captured Pensacola

and garrisoned Mobile in

November 1814.

Meanwhile

the British had were active in west Florida ostensibly in defense of their Spanish allies and in their own interests. They hoped arm the Creeks and elements of other southern tribes to engage in raiding

and irregular warfare against

American settlers in Alabama and Georgia matching the frontier warfare they were supporting from Upstate New York, through western Pennsylvania,

Ohio territory and into Kentucky

and Tennessee.

In

August 1814, a force of over 100 officers and men led by Lieutenant Colonel Edward Nicolls of the Royal Marines was sent into the region to arm, aid, and train native auxiliaries. He established the English Post at Prospect

Bluff, 15 miles above the mouth

of the Apalachicola

and 60 miles south of the Georgia line. There

he built a substantial fort to European

field standards of earth works, redoubts, and palisades with gun platforms

for several cannons. He had no

trouble recruiting native allies

or beginning to launch raids across the border in Georgia.

But

he also found large numbers of escaped slaves.

As was British policy during the war with the Americans, he offered official freedom for enlisting in armed service. He organized several hundred volunteers into four companies of the Corps

of Colonial Marines who he drilled

and trained as infantry. Although the Colonial Marines were not deployed in active combat, word of their existence spread like wildfire across Georgia slave quarters encouraging yet more runaways to seek the protection of the fort. Georgia planters were naturally furious, but

as long as Jackson’s army was away defending

New Orleans they were mostly

powerless to do anything about it.

In

November a rag-tag expedition of barely trained Mississippi militia and

allied Choctaw and Chickasaw irregulars were sent to the region to disrupt the

cross border raiding and scare off runaways.

Under Army Major Uriah Blue

the 1000 man force floundered in unfamiliar

territory and retreated to Fort Montgomery west of Pensacola without

either discovering the location of English Post or making contact with the

enemy.

Unknown

to everyone, a peace treaty already

had been signed in Ghent in December

officially ending the war. Word did not

reach the region until well after Jackson soundly

whipped a British invasion force at

New Orleans on January 8. When word

finally arrived Col. Nicolls had to abandon his fort in keeping with the terms

of the treaty. He paid off the Colonial

Marines but pointedly let them keep their weapons. Not only that, he left behind the garrison’s

cannon and a well stocked magazine.

Clearly the British were up to some

mischief and hoped that harassment

of American settlements would continue

as well as slave escapes which threatened

the economy of the region.

The

former Black militia took possession of the fort under the leadership of a

former slave named Garson and that

un-named Choctaw chief. They launched

new raids into Georgia and more runaways flocked to the protection of the fort,

which now existed in virtual

independence of any national control—Spanish,

British, or American.

Jackson

soon turned his attention to Florida and shifted much of his army to Mobile and

other posts near the Spanish possessions.

Georgia planters were officially petitioning

the government for relief and punitive expeditions

into the Spanish territories. Jackson, chomping at the bit, pressured Washington for permission to strike.

Meanwhile

in September of 1815 veteran American Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins organized

a small force of loyal Creek to attack what was now being called the Negro Fort. Garson and his men from their well defended position were easily able

to repel an assault by an inferior force. The victory

may have given the defenders a false

sense of their own power but it also emboldened them to step up raids. Slaves continued to seek refuge.

To

protect the settlers the Army built Fort

Scott on the west bank of the Flint River in the southern Georgia in early 1816. But it was almost impossible to provision

the post overland trough Georgia. The

quickest route was up the Apalachicola from the Gulf but required

trespass on officially Spanish

territory. On July 17 Navy boats

attempted to pass Negro Fort with supplies and were fired on by cannon. Four escorting soldiers were killed, and the

boats turned back. This was likely the exact result Jackson hoped for—it

provided an excuse to attack the

fort in retaliation for “hostile fire.”

A

few days later Jackson ordered Brigadier

General Edmund P. Gaines at Fort Scott to destroy the

Negro Fort. He dispatched a force of several hundred

mostly Volunteer troops with a sizable contingent of Creeks who were involved

in a tribal civil war with their cousins who had fallen in with the

Seminole. This force attacked from the north and engaged in a couple of days

of skirmishing with Black and native forces from the fort before closing in for an attack under the immediate command of Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Clinch. To counter

the Fort’s advantage in artillery, a naval force

including two gun boats under the command of Sailing Master Jarius Loomis would lend support from the river.

Hot

fire was exchanged for much of the July 27.

Several times Garson was called on to surrender. Shouts of “Give me Liberty or give me Death” were heard several times from

behind the fortifications. At some point

Garson defiantly ran up the English flag

and a red flag symbolizing no quarter given in response. This was a critical mistake for two

reasons. First, fort could expect no protection of the

long gone British but by displaying the flag they gave Jackson an excuse that it was evidence the British were still

actively meddling and sponsoring the raids into Georgia. Second, besiegers,

not the besieged traditionally

hoisted the no quarter banner after their calls to surrender were refused. Jackson would argue it was evidence that the

“bloodthirsty Blacks and savages” inside were bent on massacre.

Only

about a third of the fort’s active defenders were trained and armed veterans of

the Colonial Marine force. The rest were haphazardly armed and untrained escaped slaves, and native warriors

unused to fighting on the defense behind

walls. None were experienced gunners. Their fire from the post’s cannon mostly

sailed harmlessly over the heads of the attacking forces. When the Navy flotilla noticed this Loomis

moved his two gunboats up into close range and began to zero in on the fort

with their bow mounted gungs. Then the lucky

hot shot and the battle was instantly

over.

Only

30 of the more than 300 in the fort survived, most of them grievously wounded. That included Garson and that nameless

chief. The Americans promptly shot Garson for supposed atrocities committed in the Georgia

raids. The Chief was handed over to the

Creek allies who hacked him to death and scalped him. Black survivors were sent to slavery in

Georgia. Some natives and Black allies

who hid in the forests during the battle managed to flee east where they joined

other bands of Seminole.

Under

the terms of their enlistment the Creek were allowed to loot the ruins of the fort. They took home an impressive haul of 2,500

muskets, 50 carbines, 400 pistols, and 500 swords. Even without powder

and shot this gave that faction of

the Creek an enormous arms advantage

over their rivals and increased their regional power.

The

former Red Stick Creek were forced deeper into the Florida peninsula where they became the dominant element of the Seminole nation.

For

an action so relatively obscure in American history the brief Battle of Negro Fort had dire immediate consequences. Bitterness

over this battle led directly to the

outbreak of the First Seminole War a year later.

The three Seminole Wars would

drag on for nearly three decades and become an embarrassing debacle for the Regular

Army.

A

diplomatic crisis erupted when the Spanish,

quite naturally, vociferously objected

to the blatant encroachment on their

internationally recognized sovereign

territory. Although

the Spanish, bled dry from long years of fighting on their soil during the Napoleonic Wars, were in no

position to retaliate militarily the

brouhaha threatened delicate

negotiations over the undefined

Texas/Louisiana border. Moreover, it complicated relations with

Spanish ally Britain at a time when several important and contentious issues

remained including finishing British evacuation

of forts and trading posts

in the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi region as well as getting clear title for what Jackson had already stolen.

President Monroe’s

Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had to act nimbly on the issue. He

was also under pressure from Senators and

Congressmen from New England and other Northern States worried that Andrew

Jackson’s later unilateral seizure of Florida leading to an expansion of

Slave power. They demanded Jackson be court martialed for violating his orders and insubordination in ordering operations

on Spanish soil and attacking the Negro Fort.

Adams

ultimately vindicated Jackson arguing the attack and subsequent

seizure of Spanish Florida was a national

self-defense response to alleged Spanish and British complicity in fomenting the “Indian

and Negro War.” Adams even produced a

letter from a Georgia planter complaining “brigand Negroes [made] this

neighborhood extremely dangerous to a population like ours.”

Jackson

thus escaped the threat of court martial but fumed

that his honor had been impugned and somehow blamed Adams, who had saved his fat from the fire, for being behind a

plot to ruin him. Jackson

plotted revenge and challenged Adams, the heir apparent to Monroe in the Presidential

Election of 1824. He lost that multi-candidate election but blamed

Adams for striking a corrupt bargain with

Henry Clay to win election in a vote in the House

of Representatives after failing to get a majority of Electoral College votes. Four

years later Jackson defeated the sitting

President in a stunning political

revolution.

Thus

the obscure battle can be said to have led directly to the destruction of the

so-called Era of Good Feelings and

the National Republican Party that

had developed from the old Jeffersonian

Republicans. It led to the rise of a

new two party system represented by Jackson’s Democrats and the shaky political coalition called the Whigs. And it ushered in

decades of increasing sectional division

over the expansion of slavery.

Meanwhile Adams as Secretary of State managed to coerce the Spanish into acceding to a fait accompli and cede East Florida to the United States in the 1821 Adams-Onís Treaty. Jackson was appointed Military Commissioner—de facto governor—and a year later West and East Florida were merged into the new Territory of Florida.

The

new territory remained under and sparsely populated largely due to the seemingly endless quagmire of the

Seminole Wars and the tropical diseases rampant

in the wet semi-tropical climate. As new Englanders feared, Florida was finally admitted to the Union in 1845 as

a slave state shortly before the outbreak of the Third and final Seminole

War.

And

what about all those nameless Black and Native dead at Negro Fort? Well, what

about ‘em?

No comments:

Post a Comment