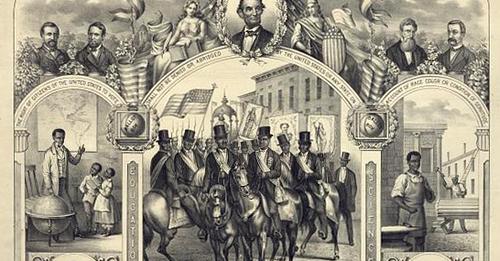

African Americans cast their first votes during Reconstruction in 1867, In 1870 the 15th Amendment was meant to specifically protect that right.

Anniversaries

of two amendments to the U.S. Constitution which protected

and extended voting rights for African Americans and the poor

were recently marked. The 15th Amendment

ratified on February 3, 1870 prohibited the Federal government

and each state from denying or abridging a citizen’s right

to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The 24th Amendment was ratified

on January 23, 1964. Yet today voting

rights are under sweeping attack not only in the states of the old Confederacy

but everywhere Republicans control state legislatures and/or governorships.

The

15th Amendment was the last of three and perhaps the least known of three

dealing with slavery and the rights of the formerly enslaved. The

13th adopted as the Civil War was drawing to a close in 1865

finally abolished slavery in all states including those which remained loyal

to the Union. It was followed

by the 14th in 1868 which guaranteed citizenship to former slaves

as well as providing due process and equal protection under the law. It is the basis for most modern civil

rights laws and has been interpreted to cover other minorities and

women as well as Blacks.

It is the most litigated of all Constitutional amendments and

the center of intense struggle by liberals and conservatives on

the Supreme Court. The current

court has a right wing majority thanks to appointments by the former

Resident of the United States and has demonstrated a willingness,

even eagerness, to roll back long-established rights.

Under

post-Civil War Reconstruction freed slaves had citizenship and voting

rights under the protection of occupying Federal Troops in the former

Confederacy. Blacks and their Republican

allies who were smeared as carpetbaggers by former Rebels were

able to elect local officials, majorities in state

legislatures, judges, governors, and members of the U.S.

House of Representatives and Senate.

Blacks thrived with new rights to own property, establish

businesses, enter trades and professions, and be educated.

But

even the most ardent supporters of Reconstruction recognized that

it could not continue indefinitely.

Former Confederates who swore loyalty to the Union had their franchise

restored as a condition of Southern states ratifying the 14th

Amendment. New generations of whites

became eligible voters when they reached maturity meaning

that whites—mostly Democrats—would inevitably return to power. The 15th Amendment was meant to ensure

that states and local governments would continue to respect the voting

rights of Blacks.

It

was a good and necessary idea as night riding and terrorism

by groups like the Ku Klux Klan were already attacking and intimidating

Black leaders and voters and even challenging Federal troops. They were seen as armed extensions of un-reconstructed

Democrats.

The

15th Amendment was simple and clear. It read:

Section 1.

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or

abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or

previous condition of servitude.

Section 2.

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate

legislation.

It

might have been effective if Reconstruction was allowed to continue for

a longer period. Unfortunately,

in 1876 the Presidential election between Republican Rutherford B.

Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden was thrown into the House of

Representatives despite Tilden’s narrow popular vote majority.

After round upon round of fruitless votes in the House where each

state delegation cast one vote, a deal was struck electing

Hayes in exchange for withdrawing troops from the South

effectively ending Reconstruction in 1877.

Without

troops to enforce the Constitution Blacks were quickly subjugated by

force and intimidation. Before 1890 virtually

all Black office holders were gone. Black

voters were purged from the rolls and state courts refused

to recognize their rights. Poll taxes

and impossible literacy tests were just two of the “legal”

means used to strip them of their voting rights. The Jim Crow Era ushered in waves of

new segregation laws and many blacks were plunged back into a condition

barely above official chattel slavery.

Without

Federal enforcement the 15th Amendment was a virtual dead letter.

The

first poll tax became effective Georgia as early as 1871. It was allowed under Reconstruction because

the poll tax impacted poor whites as well as Blacks. The idea slowly spread and really took off

after Federal troops were evacuated. By

1905 all former Confederate states had adopted a poll tax in one form or

another. Several states required that

all cumulative taxes be paid to vote meaning a would-be registrant of

middle age could be held liable for all taxes since he—only males were

then voting—turned 21.

By

the 1930s some states had abandoned the taxes, but six states retained them until

1966—Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

The states in light blue and red retained their poll taxes until the passage of the 24th Amendment, Those in gray had not formally abandon them but kept them on the books despite being unenforced.

Despite

rollbacks in some states the poll tax survived a legal challenge

in the 1937 Supreme Court case Breedlove v. Suttles, which unanimously

ruled that:

[The] privilege of voting

is not derived from the United States, but is conferred by the state and, save

as restrained by the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments and other provisions

of the Federal Constitution, the state may condition suffrage as it deems

appropriate.

Note

that the Court characterized voting as a privilege instead of a right.

Campaigns

against poll taxes began in earnest after World War II causing some

states to rescind their act. In 1948 Harry Truman considered a recommendation

of his President’s Committee on Civil Rights to legislatively

act against the taxes but in the face of united opposition from Southern

Democrats in Congress concluded that only a Constitutional Amendment would be

effective. During the post-war Red

Scare and McCarthy Era, the movement to kill the tax in Congress and

in the states ground almost to a halt as supporters were labeled Communists

because the movement had been led by avowed Marxists such as Alabama antiracist,

civil rights activist, labor organizer Joseph Gelders, New

York Congressman Vito Marcantonio, and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Later

in the 1950’s as the Civil Rights Movement in the South ramped up,

so did political pressure to end the poll tax. President John F. Kennedy administration

urged Congress to adopt and send such an amendment to the states for

ratification. He considered the Constitutional amendment the best way to

avoid a filibuster, as the claim that federal abolition of the

poll tax was unconstitutional would be moot. Some liberals

opposed Kennedy’s action, feeling that an amendment would be too slow

compared to legislation. Florida

Senator Spessard Holland, a conservative Democrat introduced the amendment

in the 87th Congress. Holland had opposed most civil rights legislation

during his career, and his support helped splinter the monolithic Southern

opposition to the amendment.

Ratification

of the amendment by state legislatures across the country was relatively quick,

taking slightly more than a year from August 1962 to January 1964. South Dakota became the 38th and deciding

state to put it over the top.

Only two former Confederate states, Florida and Kentucky,

and three Southern leaning Boarder states, Maryland, Tennessee,

and Missouri were among the supporters. Mississippi outright rejected

the amendment almost as soon as it cleared the U.S. Congress. Surprisingly,

Georgia where the poll tax originated, passed the amendment unanimously in

the Senate but did not pass the House before South Dakota secured adoption. The issue was dropped there and never

subsequently acted upon.

Long

after the amendment went into effect four additional Southern states finally ratified—Virginia

in 1977, North Carolina in 1989, Alabama in 2002, and Texas

in 2009. It is safe to say

if a vote was taken today it would not pass in the last two states which have become

radically more right wing and lead the country in voter suppression

schemes. Seven states still have not

ratified and show no inclination to do so—Arizona, Arkansas,

Georgia, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and my old

home state of Wyoming the “Equality State.”

Even

the passage of the amendment did not immediately end poll taxes. Recalcitrant states maintained the

onerous levies only applied to Federal elections for President, the House of

Representatives, and the Senate and continued to require payment to participate

in local and state elections. Arkansas

suspended its poll tax by referendum in the November 1964 General Election

several months after the amendment was ratified and did not repeal all mention

of the tax in the state constitution until 2008 but still refuses to ratify the

Federal amendment. Federal District Courts

in Alabama and Texas struck down their poll taxes in late 1965. The Supreme Court finally ruled in the

case of Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections that poll

taxes were unconstitutional even for state elections.

It

was the formal death knoll of the taxes, although attempts were made in

some states to revive fees in some guise or another. Voter

registration struggles intensified across the South with the Freedom Summer campaign

spearheaded by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

in 1964 and the Selma campaign culminating with the March to

Montgomery in1965. Both efforts were

met with violent police suppression, mass arrests, and several murders

by the Ku Klux Klan.

Norman Rockwell's stark and dramatic painting of the murder of voting rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner helped rally support for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 which finally put teeth in enforcement of the 15th and 24th amendments.

Public

horror at the murders of Freedom Summer activists James Chaney,

Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner and the deaths of Jimmy

Johnson, Unitarian Universalist minister James Reeb, and U.U. laywoman

Viola Liuzzo during the Selma campaign led directly to the passage of the landmark

Civil Rights Act of 1965. The act enforced

voting rights guaranteed by the Constitution for racial minorities throughout

the country, especially in the South. As

vigorously enforced by According to the Department of Justice, the was the most

effective piece of Federal civil rights legislation ever enacted and one

of the most far-reaching in history.

Under

the provisions of the Act states with histories of racially motivated interference

and some counties with similar histories in other states were put

under court review to any changes to their election laws. That prevented repeated efforts to find new

ways to suppress voting and led to the widespread election of Black officials

at every level in the South. It was the

most effective tool for guaranteeing access to the ballot

for decades.

But

that critical tool was crippled by the Supreme Court in the case of Shelby

County v. Holder when it ruled that a section of the Act which outlined

a formula for judicial review of state laws violates the Constitutional principles

of “equal sovereignty of the states” and federalism because its disparate

treatment of the states is “based on 40 year-old facts having no

logical relationship to the present day.” While the Court did not

completely repeal judicial review, it so gutted it as to make practically moot. Subsequent rulings have further narrowed

applicability. More recently the Court

struck down court review of most district Gerrymandering arguing how

states draw lines if their business so long as districts are fairly

equal in population.

In

response Red State legislatures have stampeded with all sorts of

laws aimed at restricting voter participation among minorities and other

populations suspected of being sympathetic to Democrats or liberals. Unlike original Jim Crow laws these actions

are not meant to completely block minority voting but to make it as difficult

and burdensome as possible to shave just enough of the vote away

to guarantee the continued domination of white conservatives.

These

outrages have helped spark a revived Civil Rights Movement

to combat the new voter repression with the John Lewis Voting Rights

Advancement Act and the Freedom to Vote Act, finally passed after

being blocked in the Senate while conservative Democrats Joe Manchin of West

Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona voted along with Republicans

to oppose a filibuster rule change that would allow election

legislation to pass with a simple majority. After the election of President Joe Biden

a deal was finally struck with Manchin causing a tie in the Senate that Vice

President Kamala Harris was able to break.

Meanwhile

angry voting rights activists took the fight back to the states where they are

met with creative new ways to suppress access to the ballot

The

old pattern of rolling back Black and minority rights is repeating itself. But it will be met with massive resistance.

No comments:

Post a Comment