On

February 5, 1917 Congress overrode President Woodrow Wilson’s

veto making the Immigration Act of

1917, also known as the Asiatic

Barred Zone Act, the law of the land.

It was the most restrictive

legislation yet enacted and banned

immigration from most of Asia and

the Pacific Islands.

China was not included only because the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 already

barred entry from that country and the Gentlemen’s

Agreement with Japan in 1907

restricted immigration from there. The

act was aimed at potential new

reservoirs of immigrants like Korea and especially India which was then exporting

cheap labor to every corner of the British

Empire and which was beginning to trickle into the States.

Wilson,

not known for his racial enlightenment,

had vetoed the measure not over its sweeping anti-oriental provisions,

but because it also required

immigrants to be literate. He feared that would choke the supply of cheap labor to American industry.

Besides

illiterates, the act banned a laundry

list of other undesirables

including “idiots, feeble-minded persons, criminals, epileptics, insane persons,

alcoholics, professional beggars, the mentally

or physically defective, polygamists, and anarchists.

Widely

derided as racist by most historians,

today the Act is held up as model

legislation by those MAGA anti-immigrants

literate in history.

Of

course, American xenophobia and anti-immigration

zeal did not end there. Decades of American industrial strife—virtual

open class warfare—in which waves of Old

World immigrants including Jews,

Italians and other Mediterranean peoples,

Poles, Slavs, and other Eastern Europeans—played prominent parts—contributed to a rise

in nativism. The Russian

Revolution and the post-World War I

Red Scare threw American oligarchs into

a panic.

Anti-Semitism in particular was on the rise because many leading labor militants, Socialists, and

anarchists were Jews.

The inevitable

result was the Immigration Act of

1924 which limited the number of

immigrants allowed entry into the United States through a national origins quota. The quota provided immigration visas to just two percent of the total number of people of each nationality in

the United States as of the 1890 Census.

The effect was to suddenly lop off the stream of mostly “swarthy” European immigration which had

flooded American shores since the Civil

War.

More than 900 Jews trying to escape Nazi Germany aboard the liner St. Louis like these looking out of portholes in Havana were denied entrance to the U.S. in 1939, Most died in the Holocaust.

The

Act was working exactly as intended when most Jews fleeing Nazism and the Holocaust were turned away.

Tens of thousands of those who were refused

visas and entry permits or who

were actually turned away including the famous case of a ship carrying

937 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution turned away from Havana, Cuba and denied entry to the US in 1939 eventually died in Nazi death camps.

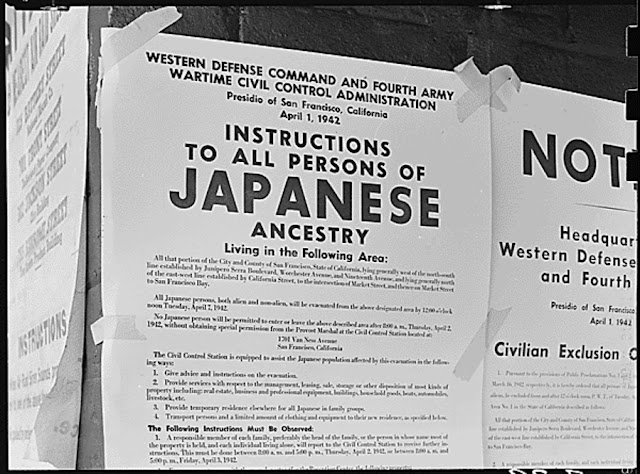

The internment of Japanese, Niseis, and their

families during World War II and the resultant loss of their homes, farms, businesses, and properties showed that fear

of the Yellow Peril was still alive and well, especially when contrasted with

the very limited internment of Germans and Italians despite large pro-Nazi and fascist pre-war

movements. Only those

who were found to be active Axis agents or were identified as positive threats

were arrested. By contrast, no such

movements existed among the Japanese and they proved to be loyal to the United

States including many who volunteered for the Armed Forces even as their families remained behind barbed

wire.

Slowly, the internments were recognized as a gross injustice and a massive violation of civil liberties. Finally in 1988 President

Ronald President Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, in which Congress apologized on behalf of the nation for the internment camps, saying they did “a

grave injustice” to those of Japanese ancestry.

Largely symbolic

reparations of payments of $20,000 to former internees were made—far less than actual losses. Many internees had already died, and their descendants received nothing. Generational

wealth remained wiped out.

Still, by the turn of the 21st century East Asians

were held up by many whites as “model minorities” for their assimilation into the dominant culture, adoption of English, academic and professional success, and perhaps most of all for by in large not “making trouble” by demanding

rights.

But even that was sometimes shaky. The same people who wailed that affirmative action programs

for African Americans at colleges and universities were unfair to more qualified white applicants also complained about the “over

representation” of Asians who had earned their places by good grades and high test scores, and demanded caps on their admissions.

Newer, poorer Asian immigrants, notably the Vietnamese boat people, and Hmongs uprooted by the American wars in Southeast Asia were deeply resented in areas where they were settled and subject to harassment and sometimes physical attack.

In 2020 the Coronavirus

pandemic ripped the scab

off the old wound. Chinese and other Asians were blamed for the spread of the disease that killed so many and disrupted lives for more than

two years. Physical

attacks and murders spread across the country often targeting the most

vulnerable—elderly immigrants

in poor urban areas—but also on campuses and in rural communities. Attackers included not just the usual suspects—white racists

and nationalists—but Blacks some of whom had long resented Asian shop

owners in their communities, blamed immigrants for vaccinations that they widely

mistrusted, and the comparative

success of the model minority.

Clearly, this nation has a long way to go.

No comments:

Post a Comment