The premier of D.

W. Griffith’s epic The

Birth of a Nation on February 8, 1915 was just the beginning of its vast influence for good and mostly bad. One of the most celebrated films in cinema

history it has been lauded and reviled. On one hand the schizophrenic flick was a stunning

technical and artistic breakthrough from

America’s most accomplished

director—an epic on a scale

never before seen chocked full of camera and editing techniques that exploded

the visual vocabulary of the medium, made long-form cinema viable, and raised

the ante on the low-brow

comedies, turgid melodramas, and

shoot ‘em ups that had dominated the silver screen. On the other hand it was proudly and avowedly racist,

romantic propaganda for night riding terrorists, and the inspiration for a resurgence of lynching and

wide-spread attacks on Black Communities like East St. Louis that year; the race

riots of 1919 in Chicago,

Washington, D.C.,

and elsewhere; and the destruction of the prosperous Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa in 1921 and the town of

Rosewood, Florida in 1925.

Fresh American racial tensions and the rise

of neo-Jim Crowism in the new Alt-Right and the empowered voice of a new

generation in the Black Lives Matter

movement have revived attention to this powerful cultural skeleton that can’t be kept in the nation’s closet.

Symbolic of that is the PBS Independent

Lens film Birth

of a Movement which premiered in 2017. The documentary chronicled:

…Boston-based African American

newspaper editor and activist William M. Trotter [who] waged a battle against

D.W. Griffith’s technically groundbreaking but notoriously Ku Klux

Klan-friendly The Birth of a Nation, unleashing a fight that still rages

today about race relations, media representation, and the power and influence

of Hollywood. Birth of a Movement, based on Dick Lehr's book The

Birth of a Movement: How Birth of a Nation Ignited the Battle for Civil Rights, captures

the backdrop to this prescient clash between human rights, freedom of speech,

and a changing media landscape.

Griffith was born the son of a Confederate officer on January 22, 1875 in rural Kentucky. His father died when he was 10 leaving the

family in poverty and costing them

the family farm. His mother’s attempt to operate a Louisville boarding house collapsed and

Griffith was forced to leave school

at 15 to support the family clerking in

a dry goods store and then a bookstore. The bookstore offered an opportunity for self-education. Later, he became stage struck and signed on to one of the touring companies that came through town working his way up from walk-ons and bit parts. He also dabbled unsuccessfully as a playwright.

In 1907 he submitted a script to the

Edison Studios in New York. Producer Edwin Porter was not impressed with the script but gave

the young actor a part in Edison’s most

ambitious picture to date, Rescued from an Eagles Nest. The next year he landed a small part

in a Biograph film. After the company’s main director Wallace McCutcheon took ill and was unable to work,

company co-founder Harry Marvin tapped

the young man as his replacement. It

was a testament to how new the

medium was and how little regard

those who ran the business had for directors and actors, who were considered disposable and interchangeable.

After his first short, The

Adventures of Dollie, Griffith churned out 47

more one and two reelers on Biograph’s assembly line. Each film was an on-the-job education and Griffith was a fast learner working with innovative camera man G. W. “Billy”

Bitzer. Griffith’s films were successful

in helping to establish the struggling studio as an industry leader. He was given his own quasi-independent production unit.

In 1910 Griffith took the unit to

the West Coast where he shot Old

California, the first film shot in the Los Angeles development

of Hollywood Land, and which first

paired him with Biograph’s rising young star Lillian Gish. Griffith

stayed out west enjoying the reliable

sunshine and good weather for outdoor shooting frequently working

with Gish.

But Griffith itched for more ambitious projects. In 1914 he pushed the reluctant studio into

allowing him to make his first feature

film—one of the first ever shot in the U.S.—the Biblical epic Judith of Bethulia

starring Blanche Sweet and

Griffith’s favorite leading man, the

diminutive Alabaman Henry B.

Walthall. But

it was an expensive film costing more than $30,000 to shoot to his

exacting standards. Biograph was

appalled and resisted his efforts to make more features causing him to exit the

company. Still, when the film was

released, it was a hit and made

money.

Griffith took his entire unit and stock company first to competing Mutual Films and then formed a studio with the Majestic Studio manager Harry Aitken

which became known as Reliance-Majestic

Studios, later renamed Fine Arts

Studio. To launch his new venture,

Griffith searched for source material

with the epic historical sweep that appealed to him. What he found was Thomas F. Dixon, Jr.’s

1905 novel The Clansman and the

successful play that Dixon had

penned based on it.

The book was already famous—and both controversial and notorious for

its portrayal of the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction era as the heroic

defenders of pure White womanhood

and valiant resistance to tyrannical oppression by carpetbagging Yankees and their crude and dangerous Black political

puppets. Griffith

resonated with the tale with every fiber of his un-reconstructed Confederate being.

Although some claim that he was naïve about the backlash that making the film would cause, Griffith was eager to

use the property to shovel the last spadesful of dirt onto the corpse

of Black equality. Dixon was at first skeptical about making the

film, but Griffith won him over with an offer of $10,000—a huge sum—for the rights to the play and Dixon’s

work on a film script.

It was money Griffith didn’t have

and couldn’t pay especially as production costs for the epic piled up. He had already had to borrow much of the capital

from the savings of his cinematographer

Blitzer. When he could not make good on the promised payment, he

instead offered Dixon 25% of the profits—the first such arrangement

in film history. It turned out to be a

very good deal for Dixon when the movie became the biggest money maker of all time, a claim it held unchallenged

until the release of Gone With the Wind in 1939. Dixon made

millions from the film—far

more than Griffith who owed everybody to pay for it.

As production got underway, Griffith

and Blitzer collaborated on the innovative techniques that would thrill and captivate cinema buffs for generations including close-ups, fade-outs, and certain kinds of tracking and panning shots. A carefully staged battle sequence made with the technical advice of West Point instructors who also lent Civil War era artillery pieces and

authenticated arms and uniforms employed hundreds of extras carefully staged to look like thousands. The long

form allowed the script to carefully

build tension over time to a dramatic

climax and the film was one of the first to mix fiction with historic

scenes and personages. In post-production tinting was used for dramatic

effect in some scenes and a score for full orchestra was composed by Joseph

Carl Breil to be performed with screenings of the three hour epic.

In addition to stars Lillian Gish

and Henry B. Walthall as the “Little

Colonel”—the heroic Confederate officer who rallies oppressed Whites to strike against Reconstruction and uppity Negros in the robes of the Ku Klux Klan—the cast

included several notables including another major female star, Mae Murray, and future stars and character actors Wallace Reid, future

director Joseph Henabery as Abraham

Lincoln, Donald Crisp as Ulysses S. Grant, future Tarzan Elmo Lincoln, Eugene Pallette, directing

great Raoul Walsh as John Wilkes Booth, and western reliable Monte Blue. Blacks were sometimes portrayed by white

actors in blackface like George

Siegmann as the mulatto henchman

to a carpetbagging Yankee, Walter Long as a lusty renegade who attacks a pure white

woman, and Jennie Lee as Mammy helping to invent an enduring

cinema stereotypes.

Even as shooting and post-production was underway, intense publicity

about the upcoming epic began to stir concern and opposition,

especially from the infant National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP) which had been founded only six years earlier

by W. E. B. Dubois, Ida B. Welles,

Mary Ovington, Henry Moscowitz, and others. Defiant and

undaunted Griffith push ahead with plans to unveil his film.

The film opened at Clune’s

Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles still bearing the

title of the book and play, The

Clansman. The very name was a red

flag to Blacks and their liberal allies. The

public furor intensified, especially in Northern cities where newspapers

editorialized against it, petitions were launched to ban it,

and noisy public meetings were raising a ruckus. The South, on the other hand, was in rapturous

anticipation of its release to their theaters and it was hailed as

vindication. Much of the country was simply eager to see

the much talked about spectacle.

Before bringing his film east,

Griffith re-named it The Birth of

a Nation. Some saw it as an attempt

to placate critics. But Griffith

stuck by his opinions he just tried to finesse

them by claiming that the U.S. emerged from the Civil War and Reconstruction as a nation unified by a common faith in White racial superiority and the

necessity of suppressing Black animal

urges. “The former enemies

of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright” a title

card at the end of the picture reads. From a public relation standpoint, he

reaped the box office benefits of the original title in the South while placating the qualms of the least aware white

Northerners.

The film opened in New York and other major cities

beginning on March 3 and was greeted by NAACP pickets. Major and minor riots erupted in Boston, Philadelphia, and

elsewhere, mostly attacks on protestors

and any Blacks that White mobs could

lay their hands on. A number of murders around the country of Blacks

were attributed to men who had

recently seen the film. Despite, and

probably because, of the violence and controversy record crowds thronged theaters.

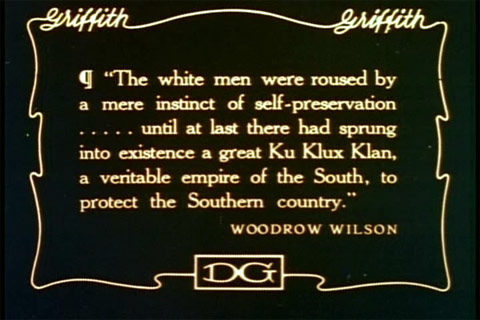

And Griffith still had an ace up his sleeve. Dixon was a former college classmate of President Woodrow Wilson.

The former Princeton President,

New Jersey governor, and leading Democratic progressive was the son of a Virginia mother with unreconstructed Confederate sympathies. As President he had already dismantled the tattered shreds of voting

rights enforcement and other protections

under the 14th Amendment

effectively driving a stake into the

heart of remnants of Reconstruction.

He had also re-segregated all

Federal agencies and services. Wilson was more than happy to host a screening of The Birth of a Nation in the White

House—the first film ever shown there—and to enthusiastically tell the press it was “like writing history

with lightning.” Not only did Griffith

exploit the endorsement in his well-oiled

publicity campaign but he added a title

card to the film quoting from Wilson’s History of the American People.

Although some cities, including Chicago, did ban the film in fear of

explosive racial unrest, huge crowds in other cities more than made up for

it. And even in most of those cities,

the movie was eventually screened after the initial wave of protests subsided.

Griffith marketed the film as no

picture ever had been before. He

invented the road show. Instead of being shown in the shoe box movie houses of the era,

little more commodious and comfortable than the nickelodeons of the film

industry’s infancy he rented the leading

auditoriums, legitimate theaters, opera houses, concert halls, and vaudeville

palaces in each city. Instead of plucking down a nickel or a dime at the box office, movie goers were advised to

buy reserve tickets at up to $1 a pop. That might not seem like much today, but it

was 20 times the cost of most movie admissions. Local orchestras

had to be engaged and rehearsed in the elaborate score. Meanwhile

the city was flooded with handbills, posters, and newspaper

advertising. The local elite turned out in white tie and tails, furs and ball gowns as if attending the opera. The working

class scrimped and saved for reduced admissions at Saturday and Sunday matinees

and showed up in their best mail-order

suits, celluloid collars, and most stylish dresses. The

film ran not just for two or three days, but for as long as the crowds kept

coming—weeks in some cities.

Griffith had several units touring

the country visiting the big cities first and working their way down to smaller

burgs in the sticks. In this way it remained in circulation for

two or three years, sometimes returning for second engagements in some

towns. Afterwards it remained available

for rent for special screenings by private groups.

The cost of all of this was

enormous, but so were the profits. The film played at the Liberty Theater in New York City for 44 weeks with tickets priced

at a jaw dropping $2.20. Total revenue from the film is difficult to gauge because of the various agreements and splits with local

theater owners and sometimes state distributors. Estimates vary widely. Epoch picture reported to its shareholders cumulative receipts of $4.8 million for all of

1917 which would have represented about 10% of total ticket sales. By 1919

that had grown to $5.2 million in world-wide

revenue. Some estimate that first

run box office sales ran to $50 million.

And money continued to pour in.

The movie’s success changed the

whole industry. Studios shifted

production to feature films. And exhibitors began to build ever larger

and more elaborate movie palaces to

accommodate the films and the expanded audience for them, a trend only briefly interrupted by World War I. The powerful operators of theater chains

became the owners of the most

important Hollywood studios, all a

direct result of the astonishing success of The

Birth of a Nation.

The film also boosted the reputation

of cinema as art rather than as low brow novelty entertainment. Newspapers added movie critics to their stables along with those covering the

theater and fine performing arts

including reporters like Carl Sandburg in Chicago. Performers like Lilian Gish, once semi-anonymous were catapulted to the glittering status of movie

stars. Griffith himself became a lionized celebrity.

But there was a much darker side

to all of this success. On the revived

interest in the Reconstruction era night

riders William Joseph Simmons inaugurated the so-called second Ku Klux Klan on Stone Mountain in Georgia where on Thanksgiving

night 1915 15 men in robes burnt a

cross. The new Klan grew slowly in

its first five years but used showings of The

Birth of a Nation as a major recruitment tool. Membership exploded in 1919 and after during

the Red Scare and during the 1920’s

the Klan was a major national

organization with widespread membership not only in the old Confederacy but

in many northern states like Indiana where

Klan members actually captured the state government. Much of the continued revenue stream

generated by The Birth of a Nation in

that decade came from Klan sponsored private showings.

As for the NAACP, the nationwide

campaign against the film failed in the sense that it prevented the

racist movie from being shown. In fact

their adamant opposition probably sold more tickets than it discouraged. But it was the first major effort by

the organization that attracted widespread public attention. It rallied

many Blacks, especially among the small, but influential urban professional middle classes to join the organization

swelling membership and establishing new chapters. Likewise white liberals flocked to the

organization and bridges were built to the more radical

elements of the labor movement

and the Socialist Party.

Despite all of the accolades and profits the film earned,

Griffith was still stung by the

criticism. His answer was his next blockbuster,

Intolerance. Griffith’s many admirers for his undoubted creative innovation multiple contributions

to the advancement of film as art have tended to become his apologists and often assert that Intolerance was made as a kind of atonement for the offences of The Birth of a Nation. Even as acute

an observer as Roger Ebert, who

usually had a nose for bullshit and a sharp political

and moral consciousness fell into

the trap of this interpretation—“...

stung by criticisms that the second half of his masterpiece was racist in its

glorification of the Ku Klux Klan and its brutal images of blacks, Griffith

tried to make amends in Intolerance (1916), which criticized prejudice.”

But Griffith regretted nothing. Instead he felt he was the victim of intolerance by critics of his

film. He reiterated this feeling of wounded self-righteousness in multiple interviews

promoting his new film.

Although Intolerance is today best remembered for its stupefying grand

scenes of the Fall of Babylon it intertwined

four separate morality tales

spanning millennia—the Babylonian tale, a Judean story picturing The

Nazarene brought to crucifixion by

intolerance, the French St.

Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of

Protestant Huguenots,

and a modern tale of a working class family destroyed by greed and busy-body do-gooders. In his

interviews Griffith often compared his persecution to Christ’s.

The two newer stories are instructive. The blame for the persecution of the

Huguenots was, of course, laid straight on the shoulders of the Catholic

Church, the object of scorn and prejudice of many of the same folks

that upheld Jim Crowe violence.

Catholics also meant dirty

immigrants to many. The newly reborn

KKK made a point of adding Catholics as well as Jews to their list of enemies

and indeed it was anti-Catholicism as much as anything that spurred its

growth in the North in states like Indiana. The chief villain of the modern story

is a liberal moral uplift society which

precipitates a deadly labor strike

when a capitalist cuts wages to give

money to his sister’s charity. Later the same charity intervenes to take

the beloved child of the innocent Dear One when the family falls

on hard times. They stand for all of the

white liberals who allied with the NAACP and especially do-gooders like pioneering social worker Jane Adams who

had harshly criticized the film.

Intolerance

cost a record shattering $2.5 million to make—far more in relationship to

the value of the dollar than the extravagant costs of the Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton version of Cleopatra or the legendary fiasco Heaven’s Gate both of which nearly ruined and bankrupted their studios. Intolerance did the same. The film was not the complete box office

failure of legend, but it failed to match the success of The Birth of a Nation and came nowhere near

recouping its costs or paying off its investors. Griffith’s studio collapsed and was sold off at fire sale prices. He had financed most of the film himself with

his earnings from The Birth of a

Nation. He was personally ruined and never recovered financially. Also the failure made other studios reluctant

to work with him.

He continued to make films, most

notably the Lillian Gish vehicle Way Down East, but he had to

relinquish his absolute control over his product and could never again attempt

a grand scale epic. In 1919 he joined Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas

Fairbanks to form independent United

Artists. The company produced Way Down East and Orphans of the Storm

successfully, but other films failed and by 1924 he left the company. He never had another hit but continued working sporadically into the early sound era. Abraham Lincoln starring Walter Huston as Abe and Una

Merkle as Ann Ruttlage with a script partly written by poet

Stephen Vincent Benét was a critical

and popular success, but like The Birth

of a Nation played fast and loose with the facts around the Civil War and

was highly colored by Griffith’s pro-Confederate bias.

Griffith then made The Struggle,

an alcoholism melodrama inspired by his own battles with

the bottle for a minor studio

financed by what was left of his own money.

It flopped. Griffith never made

another film.

He died on July 28, 1948 of a cerebral hemorrhage in the lobby of

the Knickerbocker Hotel in

Los Angeles, where he lived alone. He

spent his last years embittered and dissolute largely forgotten by

Hollywood.

He remained, however, honored by

film buffs. His greatest creation, The Birth of a Nation is high on any

list of the greatest and most influential films of all time. Because it reflected the

dominant pro Southern, anti-Reconstruction, and racist interpretation that was

central to almost all American high

school and college texts of the

era, the themes of the film were little challenged until well into the 1950’s

when historians like Eric Foner began

a reassessment of the Reconstruction

era in light of the Civil Right

Movement. By the late ‘60’s the film

was under full frontal attack by

Black scholars and sympathetic critics.

Although it retains admirers on a

technical level and several restorations

have been made and are available on CD, screenings

usually result in protests. In 1995 Turner Classic Movies (TCM) canceled a

showing of a restored print during racial tensions over the O.J.

Simpson case, although it has subsequently been shown.

None-the-less the film was selected

for preservation by the Library of Congress’s

National Film Registry. The

American Film Institute (AMI) lists it as #44 in the 100 Year….100 Movies list. Rotten

Tomato, the film buff’s web page that compiles reviews gives The Birth of a Nation a rare 100% rating.

So there you have it—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Take

your choice.

By the way, some of the dozens of

KKK splinter sects that fester in the White supremacist swamp still use the film, or clips from it as a recruiting

tool and on their web pages.

No comments:

Post a Comment