Note: The

brilliant cultural light of the Holidays obscures all else. But history continued to be ground out

despite Christmas, although it is often overlooked. Perhaps best known is General George

Washington’s crossing of the Delaware to surprise the Hessian garrison at

Trenton in 1776—a small but prestigious victory for a ragged and demoralized Continental

Congress. Also notable were the unofficial

Christmas Truces of 1914 on the Western Front of the Great War, and the final

day of the Siege of Bastogne during

the Battle of the Bulge in World War II.

In addition Christmas Eve 1913 was the occasion of the worst atrocity of

the decades long American class war when 73 striking mine workers and their

families, mostly women, and children were trapped and killed in stampede when

someone company agents shouted "fire" at a crowded Christmas party at

the Italian Hall in Calumet, Michigan.

This is the long and complicated tale of a humiliating U.S. Army defeat

in a virtually forgotten war.

The

Battle of Lake Okeechobee was just

one episode in an epic struggle that encompassed three official wars, countless scrapes,

and breaches of tenuous truces over

more than 50 years. Together they are

generally referred to as the Seminole

Wars and reduced to a mere sentence or two in most high school and many college

survey course American History text books.

Yet

more United States Government treasure was

eventually expended on the various campaigns and removal schemes than in the War

of 1812 and all of the other Indian

campaigns between the American

Revolution and the Civil War.

And more U.S. soldiers—Regulars, Volunteers, and militia died in battle or of disease than in all of the legendary post-Civil War Western Indian wars combined. At the height of the conflict—the Second Seminole War (1835-1842)—10,000 Regular Army troops were engaged—the vast majority of the Army’s total manpower—plus thousands of volunteers, militia, and auxiliaries and scouts—fought no more than 3,000

warriors. At the end of all of the waste in blood and treasure although

most of the Seminole were relocated to reservations

west of the Mississippi, a stubborn remnant held out in the depths

of the Everglades, defiant and undefeated. They remain on their lands to this day.

Florida had

famously been claimed for Spain by

the Conquistador Ponce de León in 1513 and after some unsuccessful attempts and St. Augustine—the

second oldest continuous settlement in what is now the United States—was

founded in 1565. In the subsequent two

centuries of Spanish occupation, most of the native peoples of

the peninsula were killed in warfare, died of imported European diseases

especially small pox, or were enslaved. Many of the enslaved were sold or

shipped to plantations on the profitable spice and sugar islands

of the Caribbean where the native Carib people had already been

nearly wiped out. Spain was never

able to control much of the Florida country except for areas around St.

Augustine and costal enclaves of fisher folk, wreck scavengers,

and buccaneers. But they had

nearly depopulated the whole province.

Into this void came two groups. First were Black, freemen from

the Spanish holdings, but mostly escaped slaves from both Spanish

settlements and, increasingly, runaways from Georgia and the Carolinas. Whole villages sprang up inland along

rivers away safe from Spain’s thinly spread troops.

The second were native peoples from the

north, primarily break-away Creeks and other Hitchiti

and

Muscogee speakers who settled near what is now Tallahassee in the panhandle

and around the Alachua Prairie. The Creeks were at the time the dominant tribe in the Deep South and aggressively expanding their hunting

grounds. But they were also divided between Northern and Southern branches often at odds and in by local clans often in virtual civil war.

Weaker groups fled the dominant Creeks as did members of other

tribes including Alabamas, Choctaws, Yamasees, and Yuchis. Elements of these tribes mixed and mingled often forming

villages in which the people retained

their original tribal identity but took on new group loyalties.

They

were also for the most part welcomed

by the Black villagers already there.

Escaped slaves of African origins

introduced the new arrivals to new agricultural

practices more adapted to their swampy new homes, including the cultivation of rice. Some of the arriving natives

already included Blacks in their numbers, either escaped slaves adopted into the tribe—just as there

were also White people, mostly traders, who had been adopted—or in

some cases owned as slaves. Over time more and more of the black settlers

intermarried with the natives and assimilated into their culture. Their presence also attracted a steady stream

of new runaways.

By

the early 18th Century the Spanish

had taken to calling these people Cimarrones, meaning wild ones or runaways which eventually morphed

into Seminole. Still later Yankees began to apply the term to virtually

all of the Florida peoples regardless of

their own tribal identities.

During

the chaos of the American Revolution,

fighting in the South sent a new wave of Black runaways into Florida. The British

then controlled Florida as a result of the treaties

ending the Seven Years War (French and Indian Wars in North America). Through a network of traders operating as semi-official British agents and limited military operatives took

advantage of the situation to encourage more runaways and raiding against

isolated colonial settlements. This, of course, was bitterly resented by Southern planters

who began agitating the new government

to try to annex East and West Florida, which had been returned to Spain’s weak control by the

Treaty of Paris.

With

a steady stream of slaves continuing to escape across the border, the new government

began contesting the boundary of

West Florida. By 1810 James Madison dispatched troops to occupy and annex some of the area, and there was nothing a pathetically weakened Spain could do

about it. After Andrew Jackson and

his Tennessee Volunteers defeated

the Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in early 1814,

many Creeks crossed into Florida and linked up with the Seminoles and with the Black

villages. The British armed them and encouraged forays. Jackson

drove the British and as many 700 warriors out of Pensacola, and back to the Apalachicola

River.

After

rushing to the defense of New Orleans and

his decisive victory there, Jackson

marched overland to secure Mobile

and from there was poised to take

further action against Florida. The British retained some presence in

Florida even after returning nominal

control to the Spanish and in particular armed a garrison of mostly freed

slaves at the so-called Negro Fort on

the Apalachicola. Their presence

frightened southern planters who feared it would encourage mass slave escapes

or perhaps even a slave insurrection.

When some American sailors were

killed by armed blacks, troops under

Jackson’s overall command attacked the Negro Fort, along with a large number of

his former Creek foes, recruited on

the promise that they could take

possession of the contents of the

armory of the fort. In an exchange

of artillery fire, the magazine of the Fort exploded killing almost all 300

defenders. Survivors escaped to join the

Seminole, who in turn were harassed

by their old Creek enemies, now well stocked with arms salvaged from the

fort.

The

following year, 1816, Jackson invaded

Florida on his own initiative convinced that his prestige would insulate him

from blame. He marched with 800

troops and quickly took the Spanish fort at St. Marks, where he captured a Scottish born trader and hung two Red Stick Creek (Seminole allies) chiefs

captured under ruse. Soon after he also captured a British

agent. He put both men on trial for

trading and arming the Indians and had them executed, causing an international

incident.

After

briefly returning to Tennessee, Jackson returned with an expanded army and took

Pensacola again from a 150 man Spanish garrison and about 700 Indians, both

Seminole and Red Stick Creek. His

actions flagrantly violated

international law but were said to “secure

the frontier.” Jackson was bitter

when faced with censure for insubordination, but that is another

tale. More importantly Spain realized that it could not hold Florida

if the United States chose to act against it.

They were forced to cede their

province to the U.S.

The

Americans took possession in 1821, with Jackson being appointed Territorial

Governor, a vindication of

sorts. He did not remain in active

command long, leading to a string of

weak governors to try solving the ongoing problem of the Seminole and their

Black allies.

The

military adventures leading to the

annexation of Florida became known, retroactively as the First Seminole War although most of the fighting occurred between

U.S. troops and the Red Sticks, Spanish, and allies among the Black villages

who were becoming called Black Seminoles.

With

annexation came new waves of White

settlers from adjacent states arrived, especially to the panhandle and the grass lands of the northern part of the Territory, the heart of the Seminole homeland along

the Apalachicola and in the grass prairies of the north. There the people had established substantial permanent villages with sturdy log dwellings, and extensive fields of corn

or rice in swampier areas. On the

grassland substantial herds of cattle and hogs were raised. There was general prosperity that attracted

both more run-away slaves and White land lust.

In

1823 the government negotiated the Treaty

of Moultrie Creek during meetings near St. Augustine attended by over 400

Seminole and allied tribe who elected Neamathla,

a prominent Mikasuki chief, to be their chief

representative. The treaty ceded all of the lands of the panhandle

and the northern half of the peninsula

to the United States, except for six

villages along the Apalochicola belonging to particularly influential chief. In exchange the Seminole and their allies

were given a large reservation of

about 4 million acres that ran down the middle of the peninsula from just north

of present-day Ocala to a line even

with the southern end of Tampa Bay. The boundaries were set well inland from both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts to prevent

trading for arms and to keep slaves escaping

by boat from reaching them.

The

Seminole would be able to keep Blacks who were their “lawful property” but were officially

obliged to turnover escaped slaves.

In practice that meant that the territorial governor would consider

Blacks who were culturally integrated

into the Seminole as legal property, even though United States law did not recognize the freedom that had

been granted to runaways by the former Spanish authorities.

Large sums of

money,

several hundred thousand dollars, were set aside to compensate the Seminole for their property losses in the north, expenses

in relocation, and as rations

for the first year until new crops could be harvested. Chiefs got substantial gifts—bribes—for signing.

Although

there was some resistance, most of the Seminole saw this as the best that they could do. By 1827 almost all were relocated. But the difficulty in clearing the new heavily forested, swampy land, delayed

planting new crops, then a prolonged drought

damaged crops that were planted. The

reservation was also soon over hunted leading to starvation in some villages.

Despite a general peace, more

and more bands of hunters left the

reservation in search of food, sometimes clashing with the new white settlers

in their old territory.

In

1830 Jackson was elected President and announced his intended program of removing all Eastern tribes to west of the Mississippi—including his

old enemies among the Seminole and their allies.

In

1832 the Reservation chiefs were called to Payne’s

Landing to hear a proposal to relocate them beyond the Mississippi on a

reservation already established for the Creeks, since the Seminole were

officially considered by the Government as a division of that nation. The Seminole, however, now considered themselves their own nation,

a nation historically at odds with most of the Creeks. Seven chief, however, did consent to travel west to inspect the proposed lands and to

confer with the Creeks. They were also

heavily gifted. They at first acknowledged

that the new land was “acceptable”

and agreed to sign a treaty. On returning home to the outrage of their

people most of the chiefs repudiated their agreement.

None-the-less

the Treaty of Payne’s Landing was ratified by the Senate in 1832 and the

government began to relocate those who could be persuaded to leave. That

included most of those still along the Apalochicola who suffered intense

pressure from White settlers. But most

on the Reservation refused to go, even after Jackson sent a message to a

council saying that the Army would move to impose the relocation if they did

not go. Eight of the chiefs agreed to

move west, but asked to delay the move until the end of the year. Five other important leaders refused.

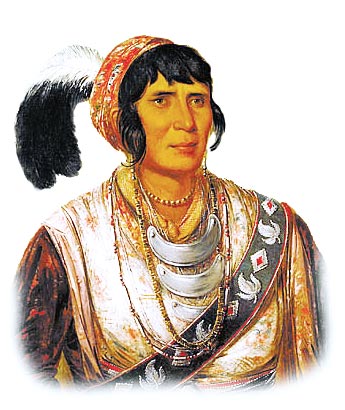

|

| Osceloa rose quickly to become the most important resistance leader among the Seminol. |

Isolated clashes between settler

and natives erupted. Tensions

mounted. One of the five resisting

Chiefs, Charley Emathla, wanting no

part of a war, led his people to Fort

Brooke, where they were to board

ships to go west. Other Seminoles

considered this a betrayal and the rising young leader Osceola met Charley Emathla on the

trail and killed him.

War broke out in 1835 as the

Territorial government mobilized the militia to move against the Seminole. Raiding parties, including some led by

Osceola which had begun raiding and burning sugar plantations along the Atlantic

coast with most of the slaves joining

them. One militia supply column with hundreds of pounds of powder and shot was captured in

another raid, which killed six guards.

On

December 23, 1835 the two companies

of U.S. Regulars, totaling 110 men, left Fort Brooke under the command of Maj. Francis L. Dade to reinforce the more isolated Fort King.

The column was shadowed

by the Seminole who ambushed it on

December killing all but three members of the command in what became known as

the Dade Massacre, one of the worst Army defeats in the young

nation’s history. The same day Osceola

killed 7 troops outside Fort King.

Fighting

and raiding spread across the peninsula with small units of regulars and

militia often coming under attack and raids on plantations spreading

south. Some officers, at least, saw

justice in the Seminole resistance. Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock, an officer

from New England whose troops found

the slaughtered remains of Dade’s

command the next February wrote home:

The government

is in the wrong, and this is the chief cause of the persevering opposition of

the Indians, who have nobly defended their country against our attempt to

enforce a fraudulent treaty. The natives used every means to avoid a war, but

were forced into it by the tyranny of our government.

Back

in Washington Jackson had no such qualms. And neither did most of the officers in the

service who hailed from the South. The Army scrambled to recover and

respond. Virginian War of 1812 hero Winfield

Scott, acknowledged to be the Army’s most

capable soldier, was brought in as the overall

commander. Meanwhile General Edmund Gaines gathered a force

of 1,100 Regulars from scattered western

posts and volunteers in New Orleans and

sailed for Fort Brook.

In

marching and counter marching

between Forts Brook and King, Gaines’ column, nearly out of food was trapped along a river at the site where

Osceola had defeated a militia force some weeks earlier. Gaines erected

a makeshift fort and sent word to Fort King to send re-enforcements. Scott would

not at first risk exposing more troops. Gaines held out against a deadly siege by hundreds of warriors

while his men were reduced to eating their mules

and dogs. The local commander at King finally

decided to ignore Scott’s order and

send relief. But instead of trapping the

attacking native forces, they just melted

away. It was another humiliating setback for the Army.

Scott

had resisted dispatching aid because he wanted to consolidate his forces and conduct a coordinated offense against the tribes. Three columns, totaling 5,000 men, were to

converge on the Cove of the

Withlacoochee, trapping the Seminoles with a force large enough to defeat

them. Scott would accompany one column, under the command of General Duncan Clinch, moving south

from Fort Drane. A second column, under Brig.

Gen. Abraham Eustis, would travel southwest from Volusia, a town on the St.

Johns River. The third wing, under the command of Col. William Lindsay, would move north from Fort Brooke. The plan

was for the three columns to arrive at the Cove simultaneously so as to prevent the Seminoles from escaping.

Eustis and Lindsay were supposed to be in place on March 25, so that Clinch's

column could drive the Seminoles into them.

Eustis

tarried to attack and burn a target of opportunity—a Black Seminole

village—and was delayed. But so were the

other two columns. By the time the columns

converged on the final day of the month, the Seminole had slipped away,

abandoning the Cove. There was only minor skirmishing with the native rear guard. Out of provisions

the now united army had to retreat to Fort Booke with nothing to show for

their efforts.

Through

the spring and summer of 1836 the Seminoles attacked and besieged a number of

forts and outposts. When they attacked

and burned the sugar mill on General Clinch’s personal plantation,

he resigned the Army and abandoned his Florida holdings for

Alabama. Meanwhile illness—yellow fever,

malaria, and dysentery swept

through the army further weakening it.

Posts, including Fort Dane and Fort

Defiance had to be abandoned. Congress swallowed hard and appropriated

another $1.5 million and authorized

volunteer enlistments for a year rather than the customary three months just to finish the year.

Newly

appointed Governor Richard Keith Call hoped

to launch a dry season summer campaign

using militia and Florida Volunteer

troops instead of the exhausted

Regulars. But gathering men and supplies

delayed him until September and the

beginning of the rainy season. After re-occupying Fort Drane, he attempted

another attack on the Seminole strong point, the Cove but his troops were

trapped across a flooded river with no tools to build rafts or canoes

and his men were peppered by rifle fire

from across the river every time they were seen

on the banks. He had to return to

base, his men half-starved when their supply

steamboat sank in the river. \

He

tried again in November, made it across the Withlacoochee, but found the Cove

abandoned. Call split his forces and marched

up the river on both banks in search of his elusive enemy. He routed an encampment on November 17 and fought a running engagement the next

day. He pursued the fleeing Seminoles

into the Wahoo Swamp on November 21

where the Indians set up a fierce resistance

to screen their families. They were

forced across a river which, once again, Call could not cross. His men were exhausted and the terms of the

Volunteers would expire in December.

Call was relieved of command and his men ordered back to Fort Brooke

where the Volunteers disbanded.

Meanwhile

Scott was relieved and replaced by

his greatest rival in the service, Major General Thomas Jesup who had just

routed rebellious Creek removal holdouts in Georgia. Jesup determined that instead of using large

units and trying to force a classic set

piece battle with the Seminole, he would wear them down by actions against their villages and a war of attrition. Jesup assembled a force of nearly 10,000,

half of them Regulars, the rest including not just the usual militia and Volunteers,

but a brigade of Marines and sailors from both the Navy

and the costal Revenue Service. The latter would man ships and boats sent up the

rivers to harass villages along their banks and disrupt communications between villages and bands. The Seminole had started the war with just

over 1,000 warriors who could not be replaced.

The war to this point had already reduced the number to something under

800.

In

January 1837 there were a number of limited but successful actions employing

this strategy including the Battle of

Hatchee-Lustee, where the Marine brigade captured between thirty and forty

Seminoles and blacks, mainly women and children, along with 100 pack ponies and 1,400 head of cattle. Some Seminole leaders began to seek peace. In March Micanopy and a few other chiefs

signed a capitulation agreeing to be

transported with their cattle and bona fide property—supposed

slaves.

As

these bands gathered in camps to await transport, they were descended upon by slave catchers who laid claim to most Blacks. Since the Seminole

could seldom, if ever, produce documentation of ownership, many were stolen from their

people.

|

| Abiaka, a Miccouskee medicine man and war chief known to the Whites as Sam Jones was a wily and elusive leader. |

Two

of the most important and successful war leaders, however, had not come in to

surrender—Osceola and Aripeka or Abiaka, medicine man and war chief

of the Miccosukee better known as Sam Jones. On June 1 these leaders and 200 Warrior

surprised the lightly held garrison at Fort Brook and liberated 700 members of

the bands surrendered by their chiefs.

This

was a severe blow to Jessup’s plans especially

since, believing that the war had essentially been won, he allowed the militia

to go home, let Volunteer enlistments expire without recruiting new ones, and

allowed the Army to reassign some of his regulars back to their usual posts. He spent the summer slowly rebuilding his

forces. Despite a steep drop in revenues caused by the Panic of 1837, Congress reluctantly appropriated

another $1.6 million for another year of campaigning.

In

the fall he resumed sending his small unit raiding parties out and his river

patrols had always continued. Many

Seminole were exhausted having been driven from their villages and unable to

plant crops and the warriors too busy to hunt.

Small family groups of Seminoles and even Blacks began surrendering to

the forces who encountered them. The Army captured the important Mikasuki chief

known as King Philip and his band

and a band of Yuchis, including their leader, Uchee Billy. Attrition was once again doing its slow work.

Jessup

had King Philip send a message to his son, the important war leader Coacoochee (Wild Cat) inviting him to a parlay. When he arrived under a flag of truce he and his companions were arrested. In October Osceola

and Coa Hadjo, another chief,

requested a parley with Jesup. A meeting was arranged south of St. Augustine

where the Army also arrested them under the White flag. All of these important prisoners were sent to

Fort Marion—the historic Spanish Castillo de San Marcos in St.

Augustine. All jammed together in a dungeon

like cell. Twenty of his cell mates

including Coacoochee and the Black war Chief John Horse escaped by squeezing their half-starved frames

through a narrow window. Osceola was too

ill to join them. He died in the same

cell not long after.

Jessup

had the respected Cherokee leader John Ross come down from Georgia to

parlay with some of the holdouts. When

Micanopy and others came in to meet the Cherokee delegation, they, too were

arrested. Ross protested but Jessup told him that any Indian who came in would be detained and deported.

After

these incidents the remaining resistors learned

never to trust Jessup.

By

late fall Jessup had built up a new large Army including Volunteer units from

as far away as Pennsylvania and Missouri. He divided his command into strong columns set

to push south down the peninsula. General Joseph Marion Hernández led a

column down the east coast, General Eustis took his column up the St. Johns River. Colonel

Zachary Taylor led a column from Fort Brooke into the middle of the state,

and then southward between the Kissimmee

River and the Peace River. Other

commands cleared out the areas between the St. Johns and the Oklawaha River, between the Oklawaha and the Withlacoochee River, and along the Caloosahatchee River. A joint

Army-Navy unit patrolled the lower east coast of Florida. Other troops

patrolled the northern part of the territory to protect against Seminole raids.

Taylor’s

campaign started well. In the first two

days after setting out on December 19 with 1000 man force more than 90 Seminole

surrendered to him. He stopped for a day

to throw up a hasty palisade, Fort

Basinger, where he left his sick and enough men to guard the Seminoles that

had surrendered.

He

then took off in pursuit of what he understood was the main body of the hostiles. He

caught up to them on a fateful Christmas Day.

About

450 Seminoles and Blacks under the leadership of Billy Bowlegs, Abiaca,

and Alligator set up well concealed defensive positions

between Lake Okeechobee and a large hammock with half a mile of swamp in front of it. Seven

foot high saw grass provided

cover and water and mire three feet deep

in places meant that horses would be

useless. The Seminole carefully prepared their position,

cutting the top off of some of the saw grass for a clear field of fire and notching

surrounding trees to steady their rifles.

Despite

this, Taylor decided to attack head on to the hammock ignoring advice to try and flank

and surround the warriors. He let

his trusted Lenape (Delaware) auxiliaries, about 80 strong, lead the way. Withering

fire sent then running back to and beyond the lines. Next in order

of battle were 180 Missouri

Volunteers who became bogged down in

the swamp and easy targets. Almost all of their officers and non-coms

were picked off. Colonel

Richard Gentry, himself mortally

wounded was unable to stop a panicked

rout, especially after some of the Seminole counter charged them.

That

left if to the Regulars, troops from the 1st,

4th, and 6th Infantry Regiments. They

pressed forward trying to maintain

formation but were soon struggling in the saw grass. The 6th was especially mauled. Lieutenant Colonel

Alexander R. Thompson, commanding and all but one officer were killed as

were most of the non-coms. When the unit

fell back and tried to reform they found only three men unwounded. Other

companies pressed the attack with

nearly the same results. Sharp fighting

continued for hours until dark when both side disengaged. The Seminole melted away in the night. In a hard day’s fight they had lost 11 dead

and a score wounded.

Taylor’s

command lost 26 dead—almost exclusively officers and non-coms and 122

injured. His auxiliaries and militia

were demoralized to uselessness and

the heavy loss to the Army’s leadership crippled it. Taylor limped back to Fort Brooke, managing

to take back with him no more prisoners, but about 150 horses and 600 head of

cattle that he had cut off from the Seminole forces. The later was a blow to the Indians.

In

his official report Taylor claimed

victory on the narrow traditional

terms of seizing control of the battlefield

at the end of the conflict. But it was a

strategic loss. Worse, a humiliating

mauling. The administration,

however, was desperate to report some

success in Florida and proclaimed Taylor a hero, promoting him to Brigadier General. The soldier earned the nick name he would wear through the Mexican War and into the White

House—Old Rough and Ready. Many

historians who have even bothered to take note of the Second Seminole War have unquestioningly swallowed the claims. Specialists in military history, even professional

Army apologists, know better.

Jessup

pressed on with his overall offensive, with Taylor’s troops rejoining the

push. In southwest Florida a joint Army-Navy

force under Navy Lt. Levin Powell

was surrounded and nearly trapped by a large Seminole force and barely made it

back to their boats with 4 dead and 20 wounded.

At

the end of January Jessup caught up with a large concentration east of Lake Okeechobee. Once again the Seminole positioned

themselves behind a hammock with their back to a river, the Loxahatchee. Once again they leveled deadly, effective

fire on charging troops. But this time

Jessup had artillery and rockets. Still, the Seminole were able to get across

the river and disappear.

That

was the last of major battles,

although skirmishes and ambushes set up by both sides persisted. Many of the Seminole were on the run deeper and deeper into

inhospitable swamps. In February

1838 the chiefs Tuskegee and Halleck Hadjo proposed surrendering if they

could remain on a smaller reservation south

of Lake Okeechobee. Jessup by now

figured this was a good deal

thinking that years of campaigning would be needed to clear all of the Seminole

by force. He agreed to the terms and forwarded

his recommendation to Washington.

The chiefs brought in many of their nearly starved people to a camp near

army headquarters which provided food

and rations. It looked like the war would be over.

But

Washington rejected the proposed treaty.

Jessup summoned the bands to deliver the

news, but they had already heard it and refused to come in voluntarily. Jessup dispatched troops to the camp where he

took more than 500 into custody with little

resistance.

In

August Jessup returned to his regular

duty as Quartermaster General of the

Army and new Brigadier Taylor was placed in command in Florida with a force

reduced to about 2,800 men. A few

thousand Seminole and a few hundred warriors remained on the loose. Taylor concentrated on defending the north

from raids and building a string of

small, closely spaced Forts

across the old Reservation connected by

wagon roads. Larger units continued

to hunt bands, but in 1838 only 200 were brought in and transported. Fighting did subside to minimal levels, but the expense of Taylor’s strategy was enormous.

Public opinion in the north

was actually swinging toward the

Seminole, and many people thought those who had fought so hard to remain had earned

the right to do so, especially since they now inhabited country thought to

be uninhabitable for white men. The new President, Martin Van Buren, was committed to continuing Jackson’s Indian

removal policy, but was not motivated by

the visceral hatred of his old boss.

Commanding General of the Army Alexander

Macomb was

sent to try and negotiate a final treaty.

Finally, Sam Jones, the most important remaining war chief sent his

chosen successor, Chitto Tustenuggee,

to meet with Macomb. On May 19, 1839, Macomb announced reaching agreement with

the Seminole. They would stop fighting

in exchange for a reservation in southern Florida.

Except

for some sporadic raiding by independent bands, the peace seemed to hold

through the summer. Then on July 23 a

new trading post on the north shore

of the Caloosahatchee River was attacked.

Most of the 23 members of the garrison and all of the civilians were

killed. Colonel William S. Harney and a handful of soldiers made it to the

boats to escape.

In

retrospect most scholars believe that this attack was not by the Seminole or

their Black allies but from remnants of the so-called Spanish Indians of south Florida who were resentful of the Seminoles entering what they considered their territory.

They hoped to sabotage the peace

and the settlement. If so, they succeeded. The war was back on.

On

the other hand after an incident near Fort

Lauderdale, Sam Jones and Chitto

Tustenuggee were accused of the Harney

Massacre. The Army tried to track

the elusive enemy with Bloodhounds with

little success since the dogs could not

track in water. Meanwhile well to

the north despite the blockhouse and

road system heavy patrolling, small raids still harassed settlers and small,

isolated troop deployments well into 1840.

In

May Taylor was replaced by Brig. Gen.

Walker Keith Armistead, Jessup’s former

second in command. He called for

another tactical change. He sent out units of 100, large enough to discourage small scale

ambush but small enough to move rapidly and what amounted to seek and destroy missions aimed at

villages and encampments and particularly planted

fields of crops and herds of cattle. Also, for the first time he allowed the

Regular Army to campaign during the

summer which Army doctrine had

avoided as the “sick season.” Previously all summer operations were

conducted by Volunteers and militia. The

tactics were working but at a cost of ramping back up Army deployment which now

included the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 6th, 8th,

and Infantry Regiments, nine companies

of the Third Artillery, and ten

companies of the 2nd Dragoons—once again more than half of the

Regular Army.

Meanwhile

far to the south Navy Lt. John T.

McLaughlin was given command of a joint Army-Navy amphibious force known as the Mosquito

Fleet to interdict arms trade to

the Seminoles from Cuba. McLaughlin established his base at Tea Table Key in the upper Florida Keys. He also sent out patrols in canoes far up rivers not previously penetrated

and attempted to cross the Everglades by boat in 1840. His first attempt failed due to illness, but

in January 1841 succeeded, demonstrating that the Government could project force even into the most remote

refuges of the Seminole.

Despite

the presence of the Mosquito force a party of Spanish Indians attacked Indian Key, a community of wreckers and

sometime pirates, killing 40 of the 50 inhabitants. A depleted garrison at Tea Table Key,

including the surgeon and hospital orderlies attempted to relieve the neighboring island with cannon hastily mounted on oar driven flat boats. But the recoil

from the cannon swamped the

boats and the raiders burned and looted the island.

Armitage

had been given $55,000 by Congress to bribe remaining leaders to relocate. In November he parlayed at Fort King with Thlocklo Tustenuggee, a Tallahassee known

as Tiger Tail, and Mikasuki Halleck Tustenuggee. But instead of offering them the generous

bribes Congress had authorized, subordinates

soon realized that he had pocketed

the money and was demanding that the

leaders relocate their bands under the

old terms of the Payne’s Landing Treaty.

And while negotiations were going on, he dispatched troops to threaten

Halleck’s village. Disgusted, the two leaders slipped away from the Army camp one

night.

Tallahassee

chief Echo Emathla did surrender his

band, but Tiger Tail and most of the tribe refused.

In

December of 1840 Harney got revenge of sorts for the attack that nearly wiped

out his command. On a tip he entered the Everglades with a party on boats borrowed

from the Marines. He penetrated deep

into the swamp before encountering a couple of Indian canoes. He set of in pursuit killing two. His guide, a Black turncoat, led him near the encampment of Chakaika and the

Spanish Indians. He attacked at dawn

with his men disguised as natives. Chakaika

was away from camp but was located and shot without offering resistance. Harney hung three captives and Chakaika’s

body beside them. He had killed four

others in the fire fights and driven a dozen or so survivors into the swamp.

In

February Coosa Tustenuggee finally accepted $5,000 for bringing in his sixty

people with sub chiefs and warriors

getting proportionally smaller settlements, reluctantly payed by Armitage under threat of exposure for embezzlement. In March the wily Coacoochee agreed to bring in his people in three

months. He accepted his bribe and took

an authorization to provide provisions for the band with him. Coacoochee then visited several forts, presented

his requisition, and made off with

supplies at each. At one he even procured a fine new horse and five and one-half gallons of whiskey.

By

spring of 1841 Armitage had sent 450 Seminoles, including 120 warriors west.

Another 236 were at Fort Brooke awaiting transportation. Others were expected to arrive shortly. Then in May Halleck Tustenuggee sent word he

would bring his band in. Armitage

figured that there were only 300 Seminole warriors left in Florida.

Congress

demanded a rapid wind down of the war and cut back on expenses, which under

Armitage had run to more than $93,000 a month.

Colonel William Jenkins Worth was

placed in command of a much reduced force.

He cut 1000 civilian employees,

mostly teamsters and carpenters, and consolidated posts. He sent

out another sweeping small unit summer campaign which finally drove the last

Seminoles out of the north including their stronghold at the Cove of the Withlacoochee,

site of earlier Army humiliations.

In

May 1841 Coacoochee was up to his old tricks at Fort Pierce where Major

Thomas Childs agreed to give him one month to bring his people in. After weeks of coming and going at the

fort—mostly leaving with supplies, Child concluded that Coacoochee did not

intent to bring his people in. He

arrested the chief and 40 others and immediately packed him on a ship bound for New Orleans. Worth, who needed Coacoochee to lure the other chiefs in was furious

and dispatched a fast boat to

intercept the ship and bring back the chief.

Under heavy guard and with no

prospect of escape he finally agreed to accept $8,000 and send messages urging

the others to come in.

211

surrendered directly as a result of Coacoochee’s plea. Hospetarke was drawn into a meeting at Camp Ogden near the mouth of the Peace

River in August and he and 127 of his band were captured. In the north most of the Seminole were

cleared out, but reduced numbers helped those remaining to stay safely in hiding. In the far south action in Big Cypress Swamp in which a number of

villages were burned helped convince others to surrender.

The

Seminole were now dispersed in small

bands across the territory and elusive.

Moreover those still on the loose included Sam Jones, and Billy Bowlegs

perhaps the most dangerous leaders of them all.

In

August 1842 First Lieutenant George A.

McCall found a band in the Pelchikaha

Swamp, about thirty miles south of Fort King. After a brief fight some were captured. Halleck Tustenuggee came to the fort to

parlay and was captured. More of his

followers were taken when they came to visit him, then McCall found and took

his camp including women and children.

Despite

the outstanding bands, in 1842 Congress felt confident to offer under the aptly

named Armed Occupation Act free land for

White settlement to any who would improve

it and “were ready to defend it

without recourse to the army.” If

this risky offer did not exactly

start a land rush, enough land hungry Americans were willing to take a chance. Previously depopulated former native lands began falling to the ax and plow.

In

August that year General William Bailey

and planter Jack Bellamy led a posse of 52 men in pursuit of Tiger

Tail’s warriors who had been

harassing the new settlers. After three

days they found their camp and attacked killing all 24 men they found. It turned out to be the last action of the long war.

A teenager, William Wesley

Hankins who executed the last warrior was credited with firing the last shot of the war.

Worth

met with many of the remaining chiefs in August. Some accepted their “gifts” and agreed to be

relocated. Other’s indicated that they would cease hostilities if allowed to

live on a reservation in southwest Florida.

Worth considered this good enough

to declare hostilities at an end.

After returning from a 90 day leave and hearing disturbing reports about

raids on northern Florida farms for livestock and provisions, Worth reluctantly

ordered the detention of the recalcitrant chiefs. Tiger Tail was brought in on a litter desperately ill. He died on board ship in New Orleans.

In

an official report Worth estimated that there

were only 300 Indians left in Florida including 42 Seminole, 33

Mikasuki, 10 Creek and 10 Tallahassee warriors all living peacefully on the reservation. This was undoubtedly an underestimation and disregarded

small bands still holding out in remote places in the north. It also does not seem to account for Sam

Jones’s band. Still it was a fraction of their pre-war population.

Less

than 3,000 had been relocated to Indian Territory on a reservation tensely

shared with the Creeks. Those people did not fare well and by 1870 their

numbers had dropped to 2,543. The total number lost to combat, starvation, and

disease is unknown.

The

government spent an aggregate of $30 to $40 million dollars on the war

depending on how it was accounted for. The Regular Army lost 1,466 men, more than

10% of all of the men who served in the conflict, most of them to disease. The Navy and Marines lost about 60. Some reports indicate that 55 Florida Volunteer

officers and men were killed in battle, but no figures are available for the

militia or from Volunteers from other states—or for those who died of disease,

surely many times the battle deaths.

About 80 White civilians are thought to have been killed.

The

Second Seminole War was a bad business all around.

Yet,

astonishingly the conflict with the Seminoles would flare again.

Although

most Seminole tried hard to stay away from contact with Whites, over the years

incidents flared up, including the killings of natives who strayed into White areas. By

the early 1850’s small scale raiding, mostly for livestock, was picking up in

the north. That brought retribution from informal posses. Political

agitation for a definitive removal

was also on the rise as were tensions.

In

December 1855 hard core rejectionists

led by Sam Jones and Billy Bowlegs decided to strike. On December 7 they ambushed a wagon patrol on

the reservation killing and scalping four men and wounding several including First Lieutenant George Hartsuff. They killed the mules, burned the wagons,

and looted the wagons. The Third Seminole War was on.

This

was not nearly as long or bloody an affair.

There were too few Seminole left for that. There were numerous skirmishes over the next

two years, but the bands remained elusive.

Harney returned to command and initiated a strategy of trying to confine the Seminole to the Everglades and

Big Cyprus Swamps hoping that winter

floods would make it impossible to

survive there. But they did. A sweep of Big Cyprus burned some villages

and destroyed some island crop fields.

On

March 15, Bowleg and Assinwar finally accepted a payment offer and agreed to go

west. On May 4, a total of 163 Seminoles were shipped to New Orleans. Four days

later Colonel Loomis declared the war to be over.

|

| The descendants of rejectionist Seminoles preserve their hard fought for culture, including the Gullah Seminole--the descendants of the slaves who found refuge with the native Florida tribes. |

However

Sam Jones and his band continued living in southeast Florida, inland from Miami

and Fort Lauderdale. Chipco’s band was living north of Lake Okeechobee,

although the Army and militia could never find them. Individual families and clans were scattered

across the wetlands of southern Florida.

These never-surrendered Indians were allowed to remain.

And

their decedents do to this day, considering themselves unconquered and beholden

to neither the State of Florida nor

the government of the United States. It gladdens

the heart a little to know that they are there.

No comments:

Post a Comment