|

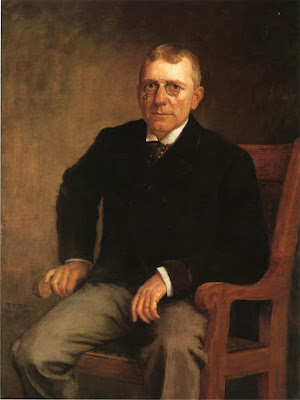

Disdained by Eastern critics, James Whitcomb Riley at least looked every inch a respectable poet.

|

high minded, serious folk— the worst

high school English teachers, academics whose careers depend on

culling ever diminish heard of obscure poets for publish-or-perish theses that no one reads, and critics convinced that only the obscure

and arcane are worthy of notice and that popularity

is vulgar. Together these folks have just about beat to death any chance

that the general public might

consider reading and enjoying poetry.

Today we offer up a poet sure to set

fire to these folks hair.

The Hoosier poet James Whitcomb

Riley may not have been the greatest American

poet. But for a good many years he was the most popular—and the most beloved.

Many of his verses were written for, and loved, by children and there was a

time when most could recite at least one of his poems by heart.

Riley was born on October 7, 1849 in

the extremely rustic village of Greenfield,

Indiana. Although his father was a lawyer with political ambitions—the boy was named for a governor of

the state—the family was still crowded into a two room log cabin.

What passed for a super highway, the

planked National Road, ran by the

cabin’s dooryard. In those days with inns

and taverns scarce, travelers on

the road often pulled up at the cabin, the largest in the village, for supper

or a place to sleep by the hearth or in the soft hay of the barn. From

the time he was a small boy, James listened to and absorbed the accents and the

stories of the visitors and entertained his family and friends with imitations.

|

Riley grew up in this comfortable frame home in Greenfield, Indiana which replaced the rustic log cabin of his birth. It is now preserved and open to the public.

|

As the village and fortunes of the

family grew, they replaced the cabin with a handsome two story white frame

house.

James was an indifferent, make that

horrible, student in the local one room academy. His mind was always

wandering to the meadows, woods, and creeks and the play of his friends.

He learned well enough to read and write, but seemed totally indifferent to

anything else. One teacher told his exasperated father, “He doesn’t know which

is more—twice ten or twice eternity.” He dropped out of school to work

odd jobs in town and on nearby farms.

His father convinced him to try

reading law with him. But that was a failure, too.

Despite his love of his town and his

friends among the lively local youths, Riley had itchy feet and a hankering to

see a bit more of the world. He took up the tramp profession of traveling sign

painter, roaming the Midwest. Later,

he became a barker in a traveling medicine show where he honed stage

skills that would later help make him famous and where he cultivated a lifelong

taste for the product, heavily laced with alcohol.

Riley didn’t write his first known

poem until the age of 21 in 1870. He sent it to a newspaper, which published it. It became a habit. The

poems, usually in dialect, reflected

his memories of the rural childhood. Newspapers began, in the custom of

the time, to reprint the poems “on exchange.”

He even started to get paid a dollar or two for a submission.

Despite this modest success, Riley

suspected that as a rural bumpkin he would never be taken seriously as a poet

by the Eastern literary establishment.

To prove his point, he perpetuated a hoax. He submitted Leonanie

an “undiscovered poem” by Edgar Allan

Poe which was universally proclaimed as a masterpiece. The Eastern

critics failed to note that Poe himself was a famous hoaxer, having published at least six in his life, the most

famous about a supposed 1844 crossing of the Atlantic by balloon.

When Riley revealed himself there were a lot of embarrassed—and

angry—critics. It is seems likely that tribe holds the grudge to this

day.

He established himself enough as a

writer to get a full time job on the Indianapolis Journal where he did

reporting and regularly contributed verse, still a popular part of any American

newspaper.

In 1883 he self-published an edition of 1000 copies of a collection, The

Old Swimmin’ Hole and ‘Leven More Poems under the pen name of Benjamin F. Johnson, of Boone. Most

poets trying this gambit ended up with crates full of unsold books and ruinous debts to the printer. Riley’s book sold out its first printing in only a

few months.

|

Riley was saluted with that singular 19th Century honor, a cigar brand and box.

|

That got the attention of local

Indianapolis publisher Merrill, Meigs

and Company which published a beautifully bound second edition under his

real name. It sold like hot cakes. Riley would be associated with

the company, which eventually became Bobbs-Merrill,

for the rest of his life. In

fact that well known publishing house was largely built on the success of its

Riley books. The first of the original ones was The Boss Girl.

Riley was able to give up his day

job, cater to his wanderlust, and promote his books when he took to the lecture

platform. With his charming wit, and theatrical style of reading he

became one of the most sought after public speakers in the country, a genuine

star of the Lyceum Circuit.

And everywhere he spoke, he sold even more books.

One of the few critics who

appreciated him, fellow Midwesterner Hamlin

Garland, noted that of American writers only Mark Twain “who had the same amazing flow of quaint

conceits. He spoke ‘copy’ all the time.” In an interview in 1892 in

Greenfield, Riley told him, “My work did itself. I’m only the willer bark

through which the whistle comes.”

Twain, by the way, was not fond of

Riley. In their only appearance together on the same program, he felt

that he was upstaged by someone plowing similar ground. There after he

avoided those literary dinners where Riley might make an appearance and

occasionally derided his adversary.

Riley’s lectures and book sales made

him the best paid writer America for

a while, surely another bitter pill

for struggling “serious” scribes. It was said copies of his books were

found in homes that contained no other save the Bible.

Riley never married. He said a

failed teenage romance back in

Greenfield had made him decide not to commit his heart. But serious

alcoholism, that all too common malady of writers, was more likely the cause.

At least one lecture tour was aborted do to drunkenness. Several attempts

of stop drinking all ultimately failed.

In 1893 Riley began boarding at the

home of his friends, Charles and Magdalena Holstein in the Indianapolis

neighborhood of Lockerbie. It

was his home for the rest of his life and his friends took care of him through

bouts of drinking and later severe health problems.

|

Although ravaged by alcoholism and in declining heath, Riley enjoyed regaling the neighborhood children with his yarns and verse.

|

By 1895 he had largely stopped

touring and his attempts to publish more “serious” poems were savaged even by

critics who had warmed to his rustic style. At home in Lockerbie he

appointed himself an uncle to neighborhood children who flocked to hear his

stories and tales.

That inspired his last, and

ultimately most successful, original book, Rhymes

of Childhood with illustrations by Howard

Chandler Christy. It was so popular through so many editions—it

remains in print today—that Riley was proclaimed the Children’s Poet, much as Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow had been years before. Twain was so moved by

this collection—and probably the memory of his dead children—that he finally

had good things to say about Riley.

In 1902 Boobs-Merrill began issuing

elegantly appointed volumes of his complete works, an honor few poets lived to

see. Riley spent his last years editing the texts. Eventually 16

volumes were issued.

Riley purchased the family homestead

in Greenfield and his brother John lived

in the house. Riley would make occasional visits.

Riley’s health had been in steady

decline since 1901. He suffered a debilitating stroke in 1910 which

confined him to a wheel chair. The loss of the use of his writing hand bothered him and he later

relied on dictation to George Ade

for his last poems and biographical sketches. By 1912 he had recovered

enough to begin recording readings

for Edison cylinders. The same

year the Governor of Indiana declared his birthday James Whitcomb Riley Day, a state

holiday observed until 1968.

He made his last visit to Greenfield

in 1916 for the funeral of a boyhood friend. A week later back in

Lockerbie, he suffered a second stroke and died on July 22nd.

Riley was widely mourned. His

books continued to be popular through the next two decades, finally falling out

of favor.

|

The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home in Indianapolis, a National Historic Site.

|

His boyhood home in Greenfield is

now a preserved historical site and his home in Lockerbie is the James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home and a

designated National Historic Site.

Our Hired Girl

Our hired girl, she’s ‘Lizabuth Ann;

An’ she can cook best things to eat!

She ist puts dough in our pie-pan,

An’ pours in somepin’ ‘at's good an’ sweet;

An’ nen she salts it all on top

With cinnamon; an’ nen she’ll stop

An’ stoop an' slide it, ist as slow,

In th’ old cook-stove, so's 'twon't slop

An’ git all spilled; nen bakes it, so

It's custard-pie, first thing you know!

An’ she can cook best things to eat!

She ist puts dough in our pie-pan,

An’ pours in somepin’ ‘at's good an’ sweet;

An’ nen she salts it all on top

With cinnamon; an’ nen she’ll stop

An’ stoop an' slide it, ist as slow,

In th’ old cook-stove, so's 'twon't slop

An’ git all spilled; nen bakes it, so

It's custard-pie, first thing you know!

An’ nen she’ll say,

“Clear out o’ my way! They’s time fer work, an’ time fer play!

Take yer dough, an’ run, child, run!

Er I cain’t git no cookin’ done!”

“Clear out o’ my way! They’s time fer work, an’ time fer play!

Take yer dough, an’ run, child, run!

Er I cain’t git no cookin’ done!”

When our hired girl ‘tends like she’s mad,

An’ says folks got to walk the chalk

When she's around, er wisht they had!

I play out on our porch an' talk

To Th’ Raggedy Man ‘at mows our lawn;

An’ he says, “Whew!” an’ nen leans on

His old crook-scythe, and blinks his eyes,

An’ sniffs all ‘round an’ says, “I swawn!

Ef my old nose don’t tell me lies,

It ‘pears like I smell custard-pies!”

An’ says folks got to walk the chalk

When she's around, er wisht they had!

I play out on our porch an' talk

To Th’ Raggedy Man ‘at mows our lawn;

An’ he says, “Whew!” an’ nen leans on

His old crook-scythe, and blinks his eyes,

An’ sniffs all ‘round an’ says, “I swawn!

Ef my old nose don’t tell me lies,

It ‘pears like I smell custard-pies!”

An’ nen he’ll say,

“Clear out o’ my way!

They’s time fer work, an’ time fer play!

Take yer dough, an’ run, child, run!

Er she cain’t git no cookin’ done!

“Clear out o’ my way!

They’s time fer work, an’ time fer play!

Take yer dough, an’ run, child, run!

Er she cain’t git no cookin’ done!

Wunst our hired girl, when she

Got the supper, an we all et,

An’ it wuz night, an’ Ma an’ me

An’ Pa went wher’ the “Social’ met,--

An’ nen when we come home, an’ see

A light in the kitchen door, an’ we

Heerd a maccordeun, Pa says, “Lan’--

O’-Gracious! who can her beau be?’

An’ I marched in, an’ ‘Lizabuth Ann

Wuz parchin’ corn fer The Raggedy Man!

Got the supper, an we all et,

An’ it wuz night, an’ Ma an’ me

An’ Pa went wher’ the “Social’ met,--

An’ nen when we come home, an’ see

A light in the kitchen door, an’ we

Heerd a maccordeun, Pa says, “Lan’--

O’-Gracious! who can her beau be?’

An’ I marched in, an’ ‘Lizabuth Ann

Wuz parchin’ corn fer The Raggedy Man!

Better say,

“Clear out o’ the way!

They’s time fer work, an’ time fer play!

“Clear out o’ the way!

They’s time fer work, an’ time fer play!

Take the hint, an’ run, child, run!

Er we cain’t git no courtin’ done!”

Er we cain’t git no courtin’ done!”

—James Whitcomb Riley

No comments:

Post a Comment