Tom Mix was big in every

way. Bigger than you can imagine. A handsome,

barrel chested man. The biggest

star. The biggest hero to a generation

or two of boys. As big as the enormous hats he wore. He

even died in a big, flashy way

speeding down an Arizona highway in

a fancy open Cord 812 Phaeton on

October 13, 1940 at just 60 years of age.

Thomas Hezekiah

Mix was born January 6, 1880 in Mix Run, Pennsylvania where his family, as the place name infers, had deep

roots. It was a small, unincorporated village in the remote north central part of the state

near what became the Elk State

Forest. His father was a stable master and the boy grew up

around horses and was an unmatched rider by his early teens.

He also was enamored

of the small traveling circus shows that came through

town. He dreamed of running away

to join the circus and practiced acts

in the barn—including using his sister as a target for knife throwing. That got him a good whipping from his father.

Restless and eager for real adventure. Mix rushed to enlist

in the Army for the Spanish American War under the name Thomas Edwin Mix—he was glad to lose Hezekiah—just

the first of many reinventions. He never saw action in that brief war, but did

become a sergeant of artillery serving in the Philippines in 1900-’01 although he was

never actually deployed against the Filipino insurrectionists.

Back stateside he

met a young woman, Grace I. Allin

and married her while on furlough in July 1902. He never returned to duty and was officially listed as a deserter that November. Desertion from the peacetime Army was not

uncommon in those days and unless the AWOL

soldier was nabbed close to base

or picked up by police somewhere on other charges the military did not have

the resources to pursue arrests. Mix often referred to his Army service in

later years, including allowing people to assume that he was in Cuba, perhaps even as a Rough Rider and some people in the Army

must have been aware of his status as he rose to fame. But no action was ever taken against him

and the Army afforded him a veteran’s funeral

with full honors. The revelation

of his status as a deserter came only when serious

biographers began to research his purposefully murky early years.

Mix’s marriage didn’t last as long

as his enlistment. It was annulled in less than a year, probably

because he had run off to Oklahoma to become a cowboy.

A master horseman already and marksman

with both a rifle and a handgun as a result of a youth spent

roaming the Pennsylvania woods and as soldier, he slid as effortlessly into his

new identity as a Colt .44 into a well-oiled holster. In no

time at all he was a top hand with a

growing reputation. But he also was something of a showman from the beginning, splitting time between real ranch work and playing the cowboy for a young nation

still enthralled with tales of the West.

In 1903 he turned up as drum

major of the Oklahoma Cavalry Band,

at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

The next year he was back in Oklahoma

in the dual roles of bartender and Town Marshall of Dewey. This short

stint as a part time lawman

would eventually loom much larger in

the legend he created about himself.

Always the lady’s man, Mix married again 1905 to Kitty Jewel Perinne of whom little

is known but whose name makes the

imagination dance. That marriage, too,

fizzled in divorce after a

year. A certain pattern in domestic

relationships was beginning to

emerge.

The same year as his marriage Mix

turned up in a troop of 50 cowboy riders

led by the legendary marshal of Deadwood and Rough Rider Captain Seth Bullock in Theodore

Roosevelt’s inaugural parade. Many

of the other riders were also former Rough Riders, leading many to conclude

that Mix was as well—an assumption he

never did anything to disclaim.

By 1906 Mix was working on the biggest and most famous of all Oklahoma ranches, the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch.

The sprawling ranch, which bred

horses as well as raising cattle, employed hundreds of cowboys. One of the wranglers was a roping

wonder named Will Rogers.

After the spring round-up hands on the ranch traditionally conducted their

own cowboy contests—rodeos they would come to be

called—displaying riding, roping, and shooting skills. Up in Cheyenne,

Wyoming they had already discovered that such cowboy games were great draws for tourists whose appetite

for cowboy adventure had been whetted

by Buffalo Bill Cody and other wild west show troupes. The 101 outfit had also been contracted to provide stock to those shows and to the rodeos

springing up around the west. Their own

private competition was itself opened to the public and began to draw

crowds. The Miller Bros launched

their own touring 101 Ranch Wild West

Show in 1906. And Tom Mix was, from the beginning the star.

Tom Mix, second from left, with members of the wild west show troupe he assembled for the 1909 Alaska-Youkon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle. He had plans to tour with the show but persistent rain in Seattle kept down receipts and his first independent circus failed.

He also competed in other rodeos and

in another type of completion called cowboy

games where riding and shooting events were combined. He was named national champion in those in Prescott,

Arizona in 1909, and Canyon City,

Colorado in 1910. In the meantime he

had married yet again, this time to horsewoman Olive Stokes on January 10, 1909 in Medora, North Dakota. Together

they appeared in other shows including the Widerman

Show in Amarillo, Texas, Seattle’s Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition,

and Will A. Dickey’s Circle D Ranch. His childhood dreams of becoming a circus

star were folding into his life as a cowboy

Mix was back at the 101 Ranch in

1910 when the Selig Polyscope Company,

an early motion picture studio,

contracted with the Miller Bros to provide stock and performers for a series of one reel films.

Westerns were already a hot commodity in the fledgling film industry. The first

American movie with a plot, the

12 minute long Great Train Robbery in 1903 set the stage for a flood of oaters.

One of the leading actors in that film, Bronco

Billy Anderson became the first

movie star that the public knew by

name and was by then producing, directing, and staring in popular westerns at Essenay Studios in Chicago.

Mix first appeared as part of the ensemble in a short Selig film, The

Cowboy Millionaire in 1909. The

following year he was featured in a

sort of documentary called Ranch

Life in the Great Southwest which showed

off his prodigious skills as a

rider, roper, and rough and tumble

cowpoke. The movie was Selig’s biggest hit to date.

In no time Mix was not only being billed as the star, he was writing and even directing his own films, which introduced

elements of comedy and romance to the action mix. Subsequent films

were not shot on the 101 ranch but at the Selig studios in the Edendale district of Los Angeles and later on western sets built at Las Vegas, New Mexico.

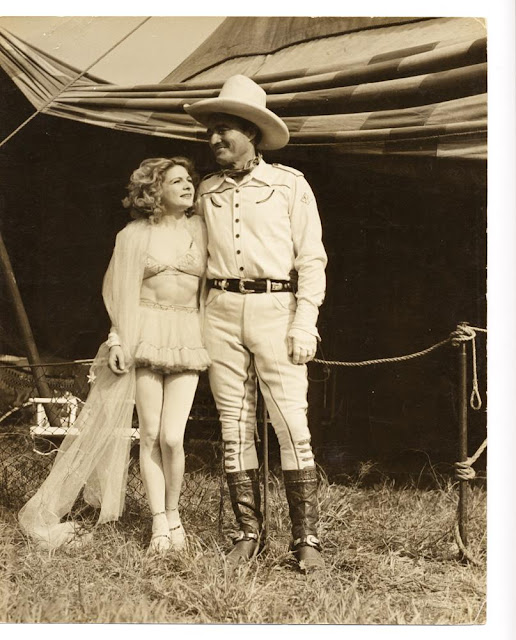

Mix with Selig co-star and third wife Victoria Forde.

In a few short years Mix made over

100 mostly single reel shorts for Selig, and some two reelers late in the association as the single reel short fell out of favor for dramatic films. Beautiful

teenage actress Victoria Forde became

his favorite leading lady and,

inevitably, his lover. After 10 years with Olivia, he divorced her

and married Forde the following year.

Mix now had three ex-wives

and a daughter, Ruth, born in 1912, who he had

to support as well as a current one—a monetary

burden that both drained him and

made him ambitious for fat paychecks.

As his marriage was crumbling so did

Selig studios, which had few hits beyond Mix.

The company went bankrupt and

William Fox bought the Edendale

studios. He also signed Mix and Forde to very generous

contracts guaranteeing Mix control of

his own films and a dedicated production

unit. That was in 1917. Mix would stay with the studio until 1928

making both him and Fox wealthy beyond

either’s dreams. And in the process

would redefine the film western in startling

new ways.

Up until this time whatever wild

plot and adventures, western films tried with greater or lesser success, for realism in costume, accouterments, and settings. Not

surprisingly. A lot of their audience could clearly recall the “Old West”

and what it looked like. Real western heroes like Buffalo Bill Cody himself or legendary

Oklahoma lawman Bill Tilghman

were showing up in films. Bronco Billy

was always careful of realistic setting.

Over at Famous Players-Lasky (the future Paramount) the biggest western star of the day, a former New York stage Shakespearian actor named William

S. Hart was a notorious stickler

for complete authenticity in his films.

Even his own Selig pictures had

mostly been rooted in the realities of ranch life.

Mix, the real cowboy, rodeo rider

and circus performer had no illusions about

his ability as an actor. But he had learned a thing or two about grabbing an audience. He knew that colorful costumes drew attention in big arenas. Instead of dusty, worn working clothes, he now appeared

in highly tailored costumes—tight trousers tucked into richly decorated high heeled cowboy boots, two pearl handled revolvers in tooled

belts strapped to his hips, crisp

shirts often double breasted

with decorative piping around a yoke and arrowhead slit pockets, silk kerchiefs

knotted at the neck. And above all, an enormous hat. No cowboy ever rode the range in anything like it.

About that hat…Photos of working cowboys from the 1870’s on show that they wore a wide variety of headgear. Usually wide brimmed hats but depending on the region, personal taste,

and what was available at the general store when they needed one the sombreros varied with peaked

crowns or flat ones, stiff brims or floppy ones, brims curled

or slouched or pushed up in front—a popular

look borrowed from cavalry troopers. Around the turn of the century cowboys on the northern part of the range began to sport what was called the Montana crease, a hat with a high crown peaked in back sloping forward with a center crease. This became the famous ten gallon hat described in dime

novels. Along the southern border with Mexico, some Texas cowboys sported a trimmed

down version of the vaquero’s

sombrero with a high, round crown

and wide brim turned up all around. Mix began to wear specially made Stetsons combining

both styles. They were big, flashy hats—he wore them in white or black interchangeably. Soon

other cowboy stars like Hoot Gibson,

Ken Maynard, and Col. Tim McCoy were wearing them.

In a case of life imitating art, they took off with real working cowboys as

well, supplanting other styles for a

decade or so. Cowboys also saved up for fancy shirts and boots

to wear to town on Saturday night or to dances,

going back to ordinary working clothes the rest of the week. Even they wanted to be Tom Mix.

Mix’s films were filled with humor.

He seemed not to take himself too seriously in stark contrast to the grim probity of William S. Hart’s

heroes. And they were chock full of action from the beginning

to the end, lots of chases, trick riding, fist fights, leaps from

great heights, and daring-do stunts

of all kinds. And Mix did all of the

stunts himself, with the camera catching

him in the kind of close-ups that

actors who used stunt doubles could

not duplicate.

Audiences ate it all up. Every Fox film seemed to top the previous

one. He did six or seven films a year

now, far down from the hectic pace of the Selig one reelers. He had a budget

for large casts, impressive scenery, big props like steam engines, paddle wheel river boats, epic

wagon trains, mass herds of real long horns—whatever he needed.

Fox built him his own facility at

the Edendale studios, a 12 acre set nick named Mixville with “… a complete

frontier town, with a dusty street,

hitching rails, a saloon, jail, bank, doctor’s office, surveyor’s office, and the simple

frame houses typical of the early Western era.” Also on the lot was an Indian village with tepees

set against plaster mountains that looked real on film, and a whole ranch set up. When scripts called for it Mix could shoot on location in California, Nevada,

and Arizona.

A big part of the show was now Mix’s

horse, Tony the Wonder Horse, a big handsome chestnut with a white blaze face and white stockings. Tony could perform all manner of tricks

and stunts including untying Mix’s

hands, opening gates, loosening his reins, rescuing Mix from

fire, jumping from one cliff to

another, and running after trains. Tony became so popular that he was sometimes co-billed with Mix and had his name in

the title of three films. His popularity inspired other equine

co-stars—Ken Maynard’s Tarzan, Gene Autry’s Champion, Roy Rogers’ Trigger,

Hopalong Cassidy’s Topper, and the Lone

Ranger’s Silver.

In his first films at Fox Forde was

his co-star and love interest. She

decided to retire and devote herself

to homemaking with the coming the couple’s daughter

Thomisina (Tommie) in 1922. After that a parade of beauties took turns being rescued and swept off their

feet by the hero.

As Mix’s films became more and more

popular, his salary grew. He made $4,000 a week in 1922 and just three

years later Fox was glad to shell out $7,500 a week—an enormous sum at the time. And Mix spent

it as fast as he made it, always paying his share to his train of

ex-wives. He always wore his immaculate

trade mark Stetsons and expensive tailored clothing, much of it western

style. He drove the latest, fastest, and most expensive cars. He erected one of the biggest mansions in Hollywood

with his own stables and an electric

sign with his name on the roof. He liked to make the rounds of nightclubs,

studio parties, premiers, and film events. He and William S. Hart, and a young filmmaker

named John Ford, regularly played cards and drank with legendary lawman,

gambler, and sporting man Wyatt

Earp. Mix was a pall bearer at Earp’s funeral

and famously broke down and cried.

When Fox refused

yet another big raise, Mix let his contract there lapse in 1928. He was tiring of movies and beginning to feel his age and the effects of accumulated

injuries from years of doing his own stunts. Joseph

P. Kennedy offered him a fat

contract to make films with his independent

studio, Film Booking Office of

America, soon to be merged into RKO. He did his last silent films there that

year. The films also featured his first

daughter Ruth. They were money makers for the small studio, but

without the vast network of Fox theaters, couldn’t generate as many viewers as his earlier

films.

Mix decided to quit films and return to his first

love—the circus. Ruth joined his

act. He was the headline star of the Sells-Floto

Circus in the 1929, 1930 and 1931seasons, pulling down $20,000 a week—more than

he ever made in pictures.

In 1931 Mix’s

marriage to Victoria Forde ended, likely because of the appearance of Mabel Hubbell

Ward who became wife number 5 in ’32.

The expense of yet another ex-wife lured him back to pictures when Universal offered him a contract to

make talkies with complete control

of his production unit. He made nine

films for Universal. Legend has it that they were failures because Mix had a high voice. Untrue

on both counts. All of the films

were box office successes, and Mix

had a fine, rich baritone voice. He was

not, however, an actor adept at reading lines and he knew it. His performances seemed more stilted than in his silents.

Both he and his

beloved horse Tony were injured. He

retired Tony and brought on Tony

Jr. But it wasn’t the same. His own injuries were becoming painful. Mix

decided to retire from film once again and return to the circus.

This time he

toured with the Sam B. Dill Circus,

which he bought out and re-named the Tom Mix Circus with Ruth,

who had starred in a score of Poverty

Row studio B westerns and serials herself, as his partner. He toured with the show in 1935 and then went

off on a European tour leaving Ruth

in charge at home. Without his draw, with then Depression hurting ticket

sales, and the expense of a large troupe, the Tom Mix Circus failed while he was away. Probably unfairly,

he blamed his daughter causing a permanent rift between them. When he died she was cut out of what was left of his

estate.

Mix had been approached several times to do his own radio show. But the money offered was far less than he

could make doing either film or circus.

Finally Ralston Purina offered

him a deal for a radio series built

around his name and character, but in which he would not have to perform. Tom Mix would be played by a series of actors

during the show’s long run from 1933 to ’51.

Tom Mix Ralston Straight Shooters starred Artells Dickson, Jack Holden

from 1937, Russell Thorsen in the early ‘40s, and Joe “Curley” Bradley from ’44 to the end of the series. Country

comedian and story teller George Gobel was one of the supporting players.

Ralston also

issued a highly popular series of Tom Mix

comic books and featured his image on

cereal boxes. Through the radio show, comics, and in the early ‘50’s television airings of his

old movies including his silent films new

generations continued to idolize

Mix even after his death.

Faced with big

bills from the collapse of the circus, Mix was lured back to movies one more

time to do a 15 episode serial, The

Miracle Rider for tiny Poverty

Row studio Mascot Pictures. The studio paid him $40,000 for just four

weeks of work. It paid off for them. They grossed over $1 million from the Saturday matinee nickels and dimes of a new generation of adoring

fans. It was Mix’s last film appearance.

Mix spent his

last years making personal appearances

around the U.S. and spending money he no longer could replace.

On October 4,

1940 Mix had been larking around

Arizona. He stopped to visit an old pal, Pima County Sheriff Ed Nichols in Tucson. Later he stopped by

the Oracle Junction Inn, a saloon and casino where he had a few

drinks and called his agent to enquire about future bookings. Then it was off to Phoenix. He was speeding down State Route 79 at an estimated

80 miles an hour when he came upon a bridge

that had been washed away by a flash flood. He slammed

on the breaks skidding on the loose gravel. An aluminum suitcase stuffed with money, traveler’s checks and jewelry

tore loose from the luggage rack on the trunk behind him

and slammed into Mix’s head, shattering his skull. The car turned

over and slid into the dry arroyo but he was already dead.

After an elaborate Hollywood funeral with full military honors, Mix was laid to rest

in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California. Despite earning

over $6 million in his movie career he left

only a few thousand dollars—and

a lot of debt in his estate. His wife, ex-wife Victoria Forde, and

daughter Thomisina each received small bequests.

Tony Jr. out lived his master, but died exactly two

years later to the day.

Mix was the inspiration of songs, and literature. Darryl

Ponicsan wrote a cult favorite novel,

Tom

Mix Died for Your Sins. Hoaxer

Clifford Irving imagined Mix joining

the Mexican Revolution Tom Mix and Pancho Villa. Philip

José Farmer made him a leading

character as Jack London’s traveling companion in two of his Riverworld

science fiction novels.

James Gardner's Wyatt Earp and Bruce Willis at Tom Mix teamed up to solve a sordid Hollwood mystry in Blake Edwars' Sunset.

Bruce Willis played Mix teaming up with James Garner’s Wyatt Earp to solve a Hollywood mystery in the 1988 Blake

Edwards film Sunset.

In the ultimate pop culture tribute, Mix is one of the faces on the cover of

the Beatles Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

No comments:

Post a Comment