Amelia

Bloomer should be remembered as one of the founding

sisterhoods of the women’s movement as

an attendee of the 1848 Seneca

Falls Convention, a lifelong suffrage

and temperance reformer, a pioneering female journalist, and the first American woman to own

and publish a newspaper. But she is

not. Instead she is remembered for a fashion fad or, if you prefer, a radical attempt to reform women’s clothing that she neither invented nor was the first to wear.

Amelia

Jenks was born on May 27, 1818 Homer, New York on the southern end of

the Finger Lakes District. Her family were respectable people of limited income but who encouraged all of

their children to get some education. Amelia, a very bright child, got a

rudimentary education in local schools. At the age of 17 she was among the first generation of young women who for

whatever reason did not immediately marry

but became schoolteachers.

After a year, she relocated to Waterloo, New York, seat of Seneca County where she lived with her newly married older sister

before taking a job as a live-in governess

to the Oren Chamberlain family.

In 1840 Amelia married attorney Dexter Bloomer and moved to a

large, comfortable home in nearby Seneca

Falls. There her life, you should

pardon the pun, began to blossom. Not only was she now a member of the

comfortable and respectable middle class

with a fine husband and growing family, that husband was unusually supportive of her expanding her

universe. Dexter recognized her keen

natural intelligence and encouraged her to read widely and acquire in that way the education she had

missed. He also made pains to include her in conversations about the politics

and current affairs in which he was

interested.

In addition to his law practice

Bloomer published the local newspaper,

the Seneca

Falls County Courier. He

encouraged Amelia to become a contributor

to its columns and as time went by and as he was increasingly engaged in

his law practice, she informally assumed some editorial duties.

Amelia also found a close,

supportive circle of

friends. It was an unusually sophisticated group, going beyond the swapping of recipients, embroidery parties, quilting bees, prayer meetings, and gossip

sessions that were the expected purview

of “hen parities.” The women, mostly Quakers and Universalists,

were widely read and included active

reformers interested in abolition of

slavery, temperance, and,

increasingly, the rights of women. The group included Elizabeth Caddy Stanton, an attractive young mother about Amelia’s

age who had even ventured to far off London

to attend an anti-slavery convention

only to be debarred from

participating on account of her sex. On

her return Stanton and her close friend, Quaker Mary Ann McClintock began to focus discussions in the group more

closely on women’s issues.

In the summer of 1848 Stanton and

McClintock, leaders of the Western New

York Anti-Slavery Society, decided to hold a hastily called convention to discuss women’s rights

and take advantage of a visit by the well know Quaker lay minister and reformer Lucrecia

Mott to the area.

Although Bloomer, whose own activism

had to this point been concentrated in Temperance work, was not one of the core organizers, she made sure that

Stanton’s call to convention was

published in the Courier and by exchange

in most of the newspapers in Upstate

New York. When the Convention convened

on July 19 Bloomer does not seem to have been in attendance. Perhaps she was among those who could not

squeeze into the Wesleyan Methodist

Chapel, which was mobbed by an

unexpectedly large crowd of both women and men.

But Bloomer did manage to find a seat in the balcony on the second day and thus got to hear the debate about the

Declaration of Sentiments. All but a final demand added personally by

Stanton—one calling for the extension of

suffrage to women—passed unanimously,

but that clause stirred vigorous debate. Even Lucrecia Mott opposed it. Stanton argued passionately for, and it was

eloquently defended by Fredrick Douglass. She also heard Mott’s stirring speech

that night. She was both impressed by it

all and more determined to make the cause of women her own.

Shortly after the convention the Seneca Falls Ladies Temperance Society

was founded and launched a newspaper for “private circulation to members.” From the beginning, Bloomer assumed editorial

direction of The Lily. At first,

aside from Temperance appeals, the paper copied other publications for the

ladies and included recipes, homemaking

tips, and advise for domestic

tranquility. But Bloomer was soon

turning more of its pages over to women’s issues. She invited Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to contribute.

By 1850, perhaps because some

members of the Temperance Society were uncomfortable by the new direction, the

Society dropped its sponsorship. Bloomer

assumed ownership and total

editorial control. She became, almost accidently, the first woman to publish

a newspaper in the United States. And it

was successful. Circulation climbed to more than 4,000 copies, many of them being sent

by mail all over New York State and into New

England. Its influence grew.

Bloomer later described why she

shifted the focus of The Lily to

women’s rights,

It was a needed instrument to spread abroad the truth of a

new gospel to woman, and I could not withhold my hand to stay the work I had

begun. I saw not the end from the beginning and dreamed where to my

propositions to society would lead me.

The fortune of the newspaper and

Bloomer’s fame took an unexpected turn in 1851.

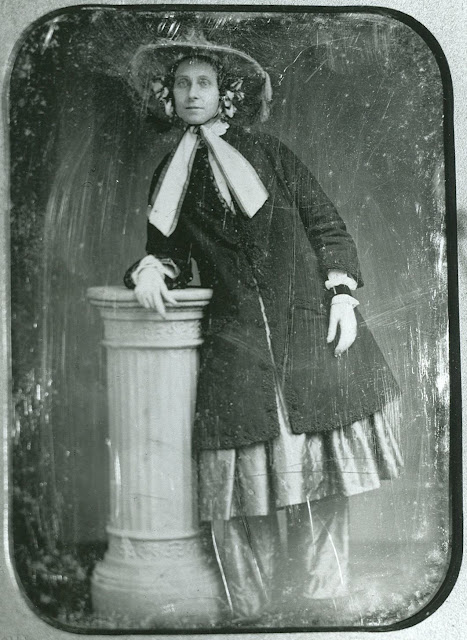

Temperance activist Libby Miller

that year adopted the fashion first suggested in the health fad magazine the Water-Cure Journal in 1849. Miller considered it a more rational costume for women who were encumbered by yards of cloth skirts and layers of petticoats. The

loose trousers, similar to those

worn in the Middle East and Central Asia were gathered at the ankles and topped by a short dress or skirt and

vest were first called Turkish Dress. Miller’s campaign to have the outfit adopted

widely received a boost when the famed English

actress and abolitionist Fanny

Kemble began to wear it publicly.

Stanton was an early adopter of the fashion and wore it on a visit to Bloomer that

year accompanied by Miller, probably with copy in hand for The Lilly. Bloomer’s first

reaction was unadulterated joy at

the liberation of the new style. She

quickly adopted it as her own and began to vigorously

advocate it in her publication.

Her articles were picked up by other

publications, including Horace Greeley’s

sympathetic New York Tribune. From

the Tribune the subject of “pantaloons for ladies” for ladies went

the 19th Century equivalent of viral.

Unfortunately most of the press was not as supportive as Greeley. They mocked

the fashion and all who wore them, singling out Bloomer for scorn.

Soon they were calling the outfit itself Bloomers. Reaction ranged

from bemusement, to savage satire in editorial cartoons, to the expected thundering of preachers denouncing

the “debauchery of our daughters.”

Bloomer was a bit mortified by the attention but refused,

at least at first, to back down.

The costume of women should be suited to her wants and

necessities. It should conduce at once to her health, comfort, and usefulness;

and, while it should not fail also to conduce to her personal adornment, it

should make that end of secondary importance.

Despite the scorn and criticism,

Bloomers did take off, at least among independent minded women, including the

first generation of female college

students. A Bloomer Ball for elegant ladies was organized in New York

City. And the fashion was readily

adopted by female travelers and in the west where commodious skirts were an impairment and inconvenience.

Who was the typical Bloomer

wearer? I picture spunky young Louisa May Alcott, a grown up Tomboy who wanted to carve out an independent career as a professional writer.

By the end of the 1850’s the fad, never widely adopted by

respectable middle class women was dying

out. Even Bloomer herself was having

second thoughts. She believed that the widespread introduction

of crinoline, which made those

layers of petticoats lighter in weight and less uncomfortable in oppressive

summer heat, made Bloomers obsolete.

The Civil War revived some interest as some nurses adopted the costume—although not those under the command of notoriously prudish Dorothy Dix. Later

in the century they were adapted as undergarments

to replace petticoats and in a simplified form as athletic wear for college girls.

There was a revival of interest during the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago

where suffragist Lucy Stone extolled

them in a speech at the Women’s Pavilion

and a fashion show displayed

up-dated versions.

Still, it took Hollywood icons like Gloria

Swanson, Gene Harlow, Greta Garbo, and Katherine

Hepburn being photographed in slacks

to begin to make pants acceptable on women.

They really took off during home

front and uniformed service

during World War II and became everyday

fashion wear standard for by most

women by the ’60’s and ‘70’s.

Despite widespread use and acceptance

Hillary Clinton found out that her pants suits could still be used against

her as a symbol of an aggressive,

assertive, unfeminine, and dumpy woman.

But arguably none of that might have

come about without Amelia Bloomer’s earnest advocacy.

As for Bloomer herself, in 1853 she

closed The Lily and moved with her

husband and family to Ohio and then

to Council Bluff,

Iowa two years later. She continued

to contribute articles to the now growing feminist press, including Stanton’s

and Susan B. Anthony’s The Revolution which bowed in 1868

and acknowledged Bloomer’s inspiration and example. Bloomer would open and edit small

publications in Iowa as well.

She dedicated herself to the struggle for women’s rights and suffrage and led campaigns in Nebraska and Iowa and served as president of the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association from 1871 until 1873.

Bloomer died on December 30, 1894 in

Council Bluffs. Although honored at the

time as a women’s rights pioneer, her contributions, except for her association

with the Bloomer, have nearly been forgotten.

Bloomer House in Seneca Falls

was listed on the National Register of

Historic Places in 1980 and in 2002 the American Library Association has produced Amelia Bloomer List annually in recognition of books with significant feminist content for young

readers.

When Anthony Met Stanton, is a life sized bronze statue in Seneca Falls, depicting Amelia Bloomer (center) introducing Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton in May 1851.

Perhaps most interestingly she is

commemorated together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet

Tubman in the calendar of saints

of the Episcopal Church on July

20. This, by the way, would come as a shock

to Stanton, a notorious Free

Thinker.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment