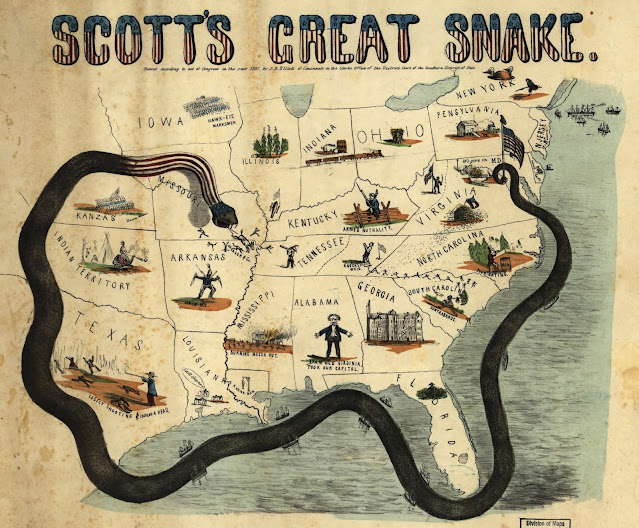

On May 3, 1861 aged Lt. General Winfield Scott,

Commanding General of the United States Army, presented President Abraham Lincoln and his Cabinet, with his Anaconda Plan to conduct the war against secessionist rebel states.

The plan was widely derided by the press and public, which believed that a quick,

decisive battle with the main Confederate

army in Virginia would win the War of Rebellion. Scott knew better. He anticipated a long and bloody conflict.

Lincoln may have wished for a short, glorious war, but the former Black Hawk War militia Captain had read everything on military strategy and tactics

that he could lay his hands on

in the Library of Congress and

sensed that his Commanding General may be right. Although he did not accept Scott’s proposal in every

detail, questioned his timeline, and felt he had to order a major attack on Richmond to keep public support, from that point on despite the public ridicule

and outcry the President conducted the war broadly on Scott’s plan.

The plan called

for:

1. Blockade ports in

the Atlantic and Gulf to reduce foreign supplies and cotton

and tobacco exports from Confederate

ports.

2. Blockade the Mississippi River to reduce grain and meat shipments from the western

to eastern Confederacy and foreign

supplies through neutral Mexico.

3. Control the Tennessee River

Valley and a march through Georgia

to prevent cooperation among the

eastern Confederate states.

4. Demonstrations against Confederate capital to keep the main Rebel Army pinned down and on the defensive with a campaign by Army troops with Navy

support along the James River.

And that is pretty much exactly how the war was won by the Union.

The Navy successfully blockaded most Confederate ports and captured key ports like Pensacola, Mobile,

and New Orleans.

Western troops, experiencing much

greater success than the ponderous Army

of the Potomac in the East, secured the length of the Mississippi with the capture of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863 (coincidently the also the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg)

splitting the Confederacy in two. Another Yankee Army drove down the Tennessee River protecting the loyal border

state of Kentucky,

splitting divided Tennessee, and setting up Sherman’s campaign through the railroad and industrial heart of

the South in northern Alabama and Georgia, including the capture of Atlanta, which cut off the lower South.

Campaigns in Virginia and along the

James, under incompetent leadership

were long, bloody, and inconclusive until the end, but without the logistical support of the rest of the

nation, Lee’s legendary Army of Northern Virginia was doomed. Just about the way Scott

had foreseen.

In 1861 Scott was winding down a 47 year Army career

serving 14 presidents from Jefferson to

Lincoln. He served in the War of 1812,

the Seminole Wars, Black Hawk War, and

Mexican War. He had been

Commanding General of the Army for twenty years, longer than anyone before

or since and was the first

officer since George Washington to

carry the rank of Lt. General. No

other officer in American history served with such distinction at every

rank—militia enlisted man, artillery captain, infantry regimental commander, leader of a victorious army in the field, and

Commanding General. He has been called

the greatest American soldier ever.

Yet he also cut something of a ridiculous figure. His once powerful 6 foot 3 inch frame had ballooned to over 300 pounds. Notoriously

vain, he swathed that mass in outrageously gaudy

uniforms with gigantic epaulets,

extravagant gold braid and decoration, every medal he was ever awarded, topped

off with a great Napoleonic era

plumed hat. Ailing from both gout

and narcolepsy—uncontrollably lapsing into sleep—he knew that he would not

be able to take command of his troops in the field.

Instead, he offered field command to fellow Virginian Col. Robert E. Lee, universally

regarded as the ablest officer in

the service. Unfortunately, unlike Scott, who unhesitatingly placed his loyalty to his nation over that

of his native state, Lee chose

Virginia and the Confederacy.

Scott had to entrust the command

of the rapidly swelling Volunteer

army to the untried hands of Brigadier Gen. Irvin McDowell. Scott despaired of both McDowell and the ill trained, short term enlisted Volunteers. During his whole career he had advocated a highly trained professional army with militias and volunteers called to service thoroughly trained before introduction

to combat.

In 1808, as a young Virginia lawyer and a corporal

in the militia cavalry, he secured an appointment as a Captain of Artillery in the tiny Regular Army. He made

his mark early by crossing his

superior, Commanding General James Wilkinson,

a corrupt scoundrel and innervate plotter. Wilkinson had

him court-martialed for insubordination and suspended

for a year. After Wilkinson was exposed

as Spanish secret agent—just one of his many

intrigues that included plotting

with Aaron Burr to set up an independent inland republic—Scott was

able to resume his duties with his reputation

enhanced.

In the War of 1812, he made his mark as a commander and a hero.

Captured in the Battle of

Queenston Heights in 1812 when the New

York Militia refused to cross into Canada

in support of his Regulars, Scott was paroled

and went to Washington to appeal to

raise regiments of regular troops.

The following year as a full colonel he planned and led the amphibious assault on Ft.

George which required a coordinated

crossing of the Niagara River

and a landing from Lake Ontario, which

was considered the most brilliant American maneuver of the war.

In 1814 as a brevet Brigadier General Scott commanded the American First Brigade in the Niagara

campaign. He had been training and drilling his regulars to a fine edge for months. But unable to secure regulation blue cloth for their uniforms, outfitted them

sharply in gray with tall shako caps. When the British saw them marching in disciplined ranks into battle, a horrified officer exclaimed, “That’s

not the Terrytown militia. Those are by God Regulars!”

Those regulars soundly whipped veteran British troops at in the Battle of Chippewa and then held the battlefield at

fiercely fought Lundy’s Lane, where

Scott and overall American commander

Major General Jacob Brown were both severely injured.

Although the invasion of Canada was stalled, Scott was hailed as a hero for showing that American troops

could beat British professionals in a stand-up battle. The battles were commemorated at the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, where

the Corps of Cadets still wears grey

uniforms and shakos. And the Confederate Army, dominated by West Pointers would, ironically adopt a gray uniform.

In the years after the war, Scott

would turn to the routine occupation

of a Regular Army Officers—Indian wars. Scott was assigned command of

1000 Regulars and Volunteers from the east to relieve expiring volunteers

units in the Black Hawk War of

1832. Unfortunately, the men brought the cholera with them, not only rendering

them unfit for service, but unleashing a deadly epidemic in the West. Although Scott never got to the battlefield, he

arrived on the scene to play a critical

role in negotiating Black Hawk’s

surrender and drafting a peace treaty.

Three years later he was commanding

a large column fruitlessly chasing hostiles in the Florida swamps during the Second

Seminole War.

No sooner was that bit of business

concluded than President Andrew Jackson called

on Scott to be the Federal brawn

behind the Force Act, meant to

compel South Carolina to honor the Tariff of Abominations in the face of Nullification threats. Sent with reinforcements

to the garrison at Ft. Sumner at Charleston, South Carolina, Scott had to juggle the bellicose desire of the President to “Hang the traitors,” and Joel

R. Poinsette’s delicate task of rallying

South Carolina Unionists while a new tariff acceptable to the state

was moved through Congress.

He got high marks for both his strong

military resolution and for local

diplomacy. When the city caught

fire, he dispatched troops from

the garrison to help quell the blaze—and

improved relations with the

locals.

With the crisis passed Jackson’s successor President Martin Van Buren turned to Scott to enforce the Cherokee Removal from the Eastern

states. Scott disapproved of the policy but did a soldier’s

duty. He considered it the low

point of his career.

He was able to negotiate the voluntary removal of a large number

under the leadership of Chief John Ross

and managed to round up other bands

with a minimum of

bloodshed. He tried, as

far as possible, to make conditions on the march tolerable,

ordering rides, assistance, and extra

rations for children, the elderly, and infirm. Where his reliable Regulars were in charge, things

went relatively smoothly.

But many bands were escorted by undisciplined volunteers

who abused, harassed, and stole from

their charges without mercy. He meant to personally

accompany the first body of evacuees on the march west from Athens, Georgia but was recalled to Washington for a delicate diplomatic mission upon

reaching Nashville.

Scott was sent to the Maine/Canada border to negotiate a peace in the bloodless Aroostook War which

threatened to erupt into another shooting war with the British.

For his success and service, he was promoted to Major General, the highest

rank active in the Army.

Scott would repeat as a diplomat

when he negotiated a solution to another border crisis with Britain, this one

over St. John Island in the Pacific Northwest in 1859.

But first there was the Mexican War. President James Knox Polk forced the war on Mexico by moving troops into disputed land between the Nueces and Rio Grande

Rivers. This army, made up mostly of

volunteers was under the command of Scott’s service rival Zachary Taylor

scored victories in heavy fighting at Monterey and Buena Vista but

was hundreds of miles north of the capital city, separated by daunting desert.

Scott conceived of a second attack by sea landing at the

port of Veracruz and driving quickly to Mexico City. He executed the first major

amphibious assault in American history when he successfully landed 12,000 Regular

Army, Marines, and well trained

Volunteers and all their artillery

and baggage outside the fortified city.

In coordination with the Naval

Squadron under the command of Commodore

Mathew Perry he laid siege to

the fortified city, which was reduced

by Army artillery and naval gunfire

and surrendered after 12 days.

With the port now open to

keep his supply line clear, Scott began his march west, roughly

following the route of Cortez.

Yellow Fever struck the Americans and Scott was only able to move with

8,500 healthy troops, among them many future

Civil War generals including Lee, U.S.

Grant, George Meade, and Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson.

Mexican President Antonio Lopez de

Santa Anna moved from the Mexico

City at the head of 12,000 well armed and trained troops. He entrenched across the road at Cerro Gordo, roughly halfway to the

city. Instead of a frontal assault,

Scott sent artillery into the rugged

mountains and enfiladed the

Mexicans in deadly fire and flanked the dug-in Mexicans, who were routed with heavy casualties.

Several other sharp engagements marked the march to the capital, culminating in the attack on the Mexican Military Academy at the castle

of Chapultepec. When that fell, Scott negotiated a peaceful

entry to the city.

The Duke of Wellington upon studying

Scott’s campaign declared him to be “the greatest living general.” The offensive is still studied

and much of later Army combat doctrine

was drawn from the experience.

The President appointed Scott the Military Governor of Mexico City,

where he drew praise for enforcing bans on looting and molestation of citizens.

He threaded the thorny issue of what

to do with the captured San Patricios—Irish deserters from

the U.S. Army who took up the

Mexican cause. He was appalled when

a court martial sentenced 72 of them to hang.

The former lawyer scoured his law books to find excuses to vacate the sentences of as

many as possible. He objected to the death penalty in 22 of the cases and later pardoned or commuted the sentences of 15 more.

With Scott still on administrative

duty in Mexico City, his rival Taylor arrived back in the States and won the Presidency on the Whig

ticket. Scott was sure he would have been a better

man for the job. Taylor died leaving Millard

Fillmore to complete his term.

When the Democrats in 1852 nominated handsome, dashing Franklin Pierce, one of Scott’s less distinguished subordinate Volunteer

generals in Mexico, the Whig convention stalemated before finally dumping

Fillmore and nominating Scott on the fifty-fourth

ballot.

The party was split on

slavery, particularly the issue of enforcing

the Fugitive Slave Act. The Party platform endorsed enforcement over Scott’s objection

leading to loss of

support of the Whig ticket in New

England, and disillusion with

the candidate among pro-slavery

southerners who jumped en-mass

to the Democrats. Despite his personal

popularity Scott carried only four states. It was also the last hurrah of the shattered

Whigs as a national party.

Scott, his vanity bruised,

none-the-less went back to work as Commanding General.

It is fortunate for Lincoln and

the Union that he stayed as long as he did. But after McDowell’s

raw and ill trained volunteer army was routed

at First Bull Run, Lincoln had to turn to the ambitious

Democrat George McClellan as his field

commander. McClellan, popular with the troops and with the press, was openly insubordinate to the Commanding General and plotted to replace him.

Seeing the writing on the wall and

in ill health, Scott finally retired

in November. McClellan got his job while retaining field command.

McClellan would be just as insubordinate to the President as he was to

Scott and despite assembling a massive,

well trained, and well appointed Army would prove too timid. Lincoln replaced him as Commanding General with

General Henry “Old Brains” Halleck,

a plodding administrator who did not get in the way of the field commanders like Grant and Sherman who

could actually win battles.

Winfield Scott, Old Fuss and

Feathers as he was known by his men, died

at West Point in 1866.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment