On

November 5, 1968 a slender and bespectacled early childhood educator became the first Black woman elected to the United

States Congress. It would not be the

last of Shirley Chisholm’s

political firsts.

Shirley Anita St. Hill was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 30, 1924 the oldest of four daughters to immigrant parents Charles St.

Hill, a factory worker from Guyana, and Ruby Seale St. Hill, a seamstress from Barbados.

When

her mother struggled to raise her children while working, Shirley and two sisters were sent to live with their grandmother in Barbados in 1921. They lived on her grandmother’s farm in the Vauxhall village in Christ

Church where they attended a one

room school. She later wrote of the

experience:

Years later I

would know what an important gift my parents had given me by seeing to it that

I had my early education in the strict, traditional, British-style schools of

Barbados. If I speak and write easily now, that early education is the main

reason….Granny gave me strength, dignity, and love. I learned from an early age

that I was somebody. I didn’t need the black revolution to tell me that.

The

girls returned to New York in 1934 during the depths of the Depression. A star student in

New York public schools, in 1940 Shirley was admitted to Girls’ High School in Bedford–Stuyvesant, a highly regarded, integrated school that attracted girls

from throughout Brooklyn. From there she went on to Brooklyn College from which she graduated with honors

in1946. During college she was noted for

her debating skills. Her impressed instructors urged her to

consider entering politics, but she demurred

saying that she had a double handicap as both Black and female. Instead, she became a pre-school teacher.

During

the post-war years Shirley met Jamaican immigrant Conrad O. Chisholm, a private detective, of all things and perfect for the film noir era. The young couple celebrated a festive wedding attended by many in Brooklyn’s

large Anglo-Caribbean community.

As Shirley

Chisholm she continued to work while earning her MA in elementary education

from Teachers College at Columbia University in 1952. Armed with the graduate degree she became the

Director of the Friends Day Nursery in Brownsville,

Brooklyn, and then the Hamilton-Madison

Child Care Center in Manhattan.

And from 1959 to 1964, she was an educational

consultant for New York City

Division of Day Care.

As

an authority on issues involving

early education and child welfare with

a growing reputation, Chisholm was drawn to politics where she hoped to advance

those issues and raise the voice of both Blacks and women. She started as a volunteer with the then

still White male Bedford-Stuyvesant

Democratic Club when such local clubs were the street-level power centers for New

York City Democratic Party. In

the face of racial and gender

inequality, she also joined local chapters of the League of Women Voters, the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League, and the National Association of College Women.

Her political

acumen and wide contacts led Chisholm to run for the New York State Assembly in 1964.

She became just the second African

American in the Legislature. She was re-elected to two more terms serving until 1968. She accomplished much in Albany including opposing an English language literacy test for voting because a person “functions better in his native language is

no sign a person is illiterate.” She was a prime mover in getting unemployment benefits extended to domestic workers, and enacting the SEEK program (Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) which provided disadvantaged students the chance to

enter college while receiving intensive remedial education.

She

also worked tirelessly to expand Black voice and influence in government. By early 1966 she was a leader in a push by

the statewide Council of Elected Negro

Democrats for Black representation on key

committees in the Assembly.

In

1968 Federal Court ordered redistricting

created the newly re-drawn 12th

Congressional District centered on Bedford-Stuyvesant which was expected to

give Brooklyn its first Black Representative. After the previous white Representative

chose to run in a more favorable District, Chisholm faced two other Black

candidates in the April primary—State Senator William S.

Thompson and labor union officer

Dollie Robertson. She ran with the

campaign slogan “Unbought and Unbossed,” an acknowledgement that the fading

remnants of the old Tammany machine

backed Thompson. She won the nomination.

Her rising star was recognized when she was

elected as the Democratic National

Committeewoman from New York State and

attended the notoriously raucous Democratic

National Convention in Chicago that

August, her first introduction to the national

stage.

Despite

this, political odds makers rated

her as an underdog in the November General Election where she faced a much

better known opponent—James Farmer,

the Director of the militant civil rights organization the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and a vocal proponent of the

rising Black Power movement. Farmer ran on the Liberal Party ticket and had the support of the New York Republicans who still had the allegiance of many older Blacks who

remembered it as the party of Lincoln. But Chisholm crushed him in the election

by a two to one margin thanks to her deep roots in the community and the

perception that Farmer, a Southerner,

was an interloper.

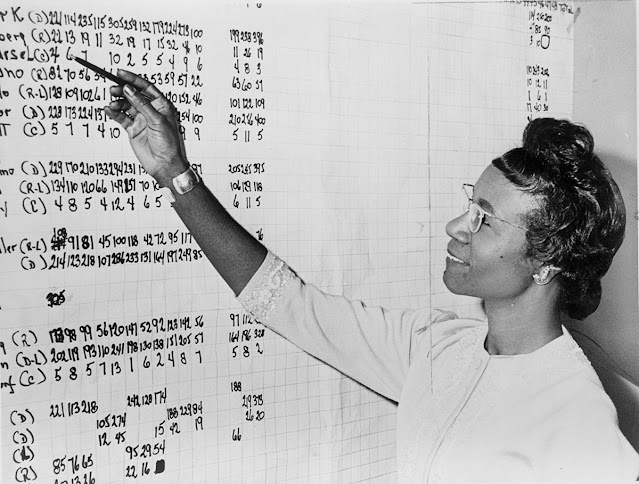

Chisholm celebrated her election to Congress with supporters in Brooklyn.

Congress

did not exactly open its arms to the freshman member from New York.

She was assigned to the Agriculture

Committee which she considered was an insult to her urban district. But a close

friend and supporter Rabbi Menachem M.

Schneerson, the Hassidic Lubavitcher

Rebbe, suggested that she use to committee to expand food assistance to the poor. She then partnered across the aisle with Republican

Senator Robert Dole of Kansas to

expand the Food Stamp program

and later played a critical role in the creation of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants

and Children (WIC) program.

That

kind of political practicality came

into play in her second term when she voted for Hale Boggs of Louisiana for

Democratic House Majority Leader

over John Connors of Michigan.

Despite affection for Connors, she could count votes and knew there was no way

he could then be elected. She supported

Boggs over a symbolic protest. The House leadership rewarded her with an

appointment to the Education and Labor

Committee where she felt she could best represent her constituents.

Chisholm

was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971 and the

same year, she was also a founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus.

Chisholm's presidential bid announcement rally at the Concord Baptist Church in Brooklyn, New York in January 1972.

Late

in 1971 Chisholm decided to launch a long-shot

campaign for the 1972 Democratic Presidential

nomination as a strong opponent of the Vietnam

War and critic of military spending as

well as an unabashed supporter of women’s

rights and for social justice. At the Brooklyn announcement of her bid, she

called for a “bloodless revolution”

at the Democratic Convention in Miami. She told her supporters:

I am not the

candidate of Black America, although I am Black and proud. I am not the

candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and

equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people and my presence before

you symbolizes a new era in American political history.

She

became the first Black to seek a major

party nomination for President and the first woman to run as a

Democrat. The political establishment,

including most of the male members of the Congressional Black Caucus, was hostile or indifferent. The press regarded her as a merely symbolic candidate and largely ignored

her campaign. Without deep pocket donors her campaign was cash strapped from the beginning—she raised and spent only about $300,000 over the entire primary and caucus season and

was only able to get on primary ballots in 14 states and could not even afford

to visit many of them. Yet she plunged

ahead.

It

was a complex and crowded field led

by anti-war Senator George McGovern

of South Dakota and by the Happy Warrior, former Vice President and 1968 nominee Hubert Humphrey. Alabama Governor and ardent segregationist George Wallace was

running this time as a Democrat and was expected to sweep much of the South and pick off votes of disgruntled

working class Whites in Rust Belt States. Henry “Scoop” Jackson,

the Senator from Boing, was running

as a pro-war moderate liberal and North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford hoped

to woo moderate Southerners.

Chisholm

set tongues wagging when she visited Wallace in his hospital room after he was shot

in an assassination attempt in May. She cited common humanity and noted that the African-American community had

lost leaders to assassins. None-the-less,

she was heavily criticized by many Black leaders.

It

was only after Wallace was shot that Chisholm was given the same Secret Service protection as the other

candidates despite at least three credible

threats on her life. Prior to that

her husband was her personal bodyguard.

She

was blocked from participating in televised

primary debates, and after taking legal

action, was permitted to make just one broadcast

speech.

Chisholm

won the largely meaningless New

Jersey Primary “Beauty Contest”

but gained only two delegates because she did not field a full slate of Convention Delegates. Overall, she won 28 delegates during the

primaries process and garnered 430,703 votes, 2.7% of nearly 16 million cast

and represented seventh place among the Democratic contenders.

At

the Convention in July, it was apparent that McGovern was the likely winner,

but Humphrey still hoped to block his nomination. He released his Black delegates to vote for

Chisholm if they wished. Mississippi had

two contesting delegations—Regulars who supported Wallace or

Jackson, and “Loyalists”

mostly leaning for McGovern. The

Loyalists won the credential fight but

some McGovern supporters became angry at public statement of the candidate

which seemed to back pedal on his

pledge to withdraw from Vietnam. She

ended up with 12 of the state’s 25 votes.

Mostly Black uncommitted delegates

from Louisiana cast 18.5 of its 44

votes for Chisholm. In the end, Chisholm

won 152 delegate votes and finished fourth in the rollcall balloting.

Still,

her historic bid was not a failure. She

declared that she ran, “in spite of hopeless odds ... to demonstrate the sheer

will and refusal to accept the status quo.”

It

was not a Democratic year anyway.

McGovern stumbled to the worst Electoral

College drubbing in history. Of course, Richard Nixon’s totally unnecessary spying on the Democratic National Committee and assorted dirty tricks soon took down his Presidency.

Chisholm

returned to the House where she continued to pile up achievements. She worked to improve opportunities for inner-city residents, was a vocal

opponent of the Draft and supported spending increases for education,

health care and other social services offset by reductions in military

spending. She also worked for the revocation of the Post-war Red Scare era McCarran

Act of 1950 which authorized some of the worst domestic political repression in American history as well as the

establishment of detainment camps that

were originally intended for Communists and

leftists but which the Nixon administration

was considering using to detain Black

militants, student radicals, and

anti-war leaders. During the Jimmy Carter administration, she advocated for equal treatment of Haitian refugees with anti-Castro

Cubans.

In

1977 Chisholm was elected to the House Leadership

as Secretary of the House Democratic Caucus, a position that had become reserved for a

woman.

But

the same year her long time marriage to Conrad Chisholm ended in divorce. A year later she married Arthur Hardwick, Jr., a former New York State Assemblyman whom Chisholm had known

when they both served in that body and who was then a Buffalo liquor store owner.

Chisholm’s

drive to secure a minimum wage for

domestic workers finally paid off, in part because of her long ago kindness to

George Wallace. Wallace had returned to

the Governor’s Mansion in Montgomery still wracked with pain from

his injuries and confined to a wheelchair. He also pursued a new policy of racial reconciliation with the

appointment of Blacks to key positions on his staff and in the

administration. Wallace used his

considerable influence with several Southern members of Congress to convince

them to support Chisholm’s bill.

Her

husband was seriously injured in an auto

accident and Chisholm was dismayed by the disarray of liberal politics in the

early years of the Reagan

Revolution. She announced her retirement

after her seventh term, leaving Congress after the 1982 election.

She

taught at Mount Holyoke College as

the Purington Chair at the

prestigious women’s college, a position previously held by W. H. Auden, Bertrand Russell, and Arna Bontemps. She remained active in

politics and co-founded the National Political Congress of Black Women

and African-American Women for

Reproductive Freedom. She supported Jesse Jackson’s two campaigns for the

Democratic Presidential nomination. She

also spoke widely on college campuses.

Arthur

Hardwick died in 1986 and her own health began to decline. In 1991 she retired to Florida. In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated

her to be Ambassador to Jamaica, but she declined due to

poor health. The same year she was inducted

into the National Women’s

Hall of Fame.

Chisholm

died on January 1, 2005, in Ormond Beach,

Florida after suffering several

strokes. She was buried in the Oakwood Mausoleum at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo next to

her second husband.

Chisholm’s

posthumous honors included being

portrayed on a United States Postal

Service Black Heritage First Class stamp in 2014 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Barack Obama. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo dedicated the Shirley Chisholm State Park, along 3.5 miles of the Jamaica Bay coastline. A monument

was dedicated in New York City’s Prospect

Park, the first woman to be so honored by She Built NYC, a public-arts campaign that honors

pioneering women by installing monuments that “celebrate their extraordinary

contributions to the city and beyond.”

But

Chisholm’s real legacy was the doors she opened. Beneficiaries include Geraldine Ferrero, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi and many of the women elected

in the 2018 Blue Wave election and since then

No comments:

Post a Comment