On June 25, 1863 Olympia Brown was ordained as a minister by the St. Lawrence Association of Universalists in New York State. She was the first woman in America ordained as a minister with full denominational authority. A handful of other women had been ordained by individual congregations, been licensed to preach, or founded their own churches.

The twenty-eight year old Brown came fully and formally educated in a denomination—Universalism—that had often relied on self-educated preachers to spread the liberal gospel of Universal Salvation.

Brown was born to Vermont Yankee stock on a pioneer farm near Prairie Ronde, Michigan in 1835. The family of devout Universalists placed a high value on education. Her father built a schoolhouse on his farm and raised money from neighbors to hire a teacher. Later Olympia, the eldest of four children, attended school in the nearby aptly named town of Schoolcraft.

But she craved more than semi-frontier schools could offer. Her father agreed to enroll her in prestigious Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in Massachusetts, but the school’s strict Calvinism deeply offended her sensibilities.

She was much happier at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, which was presided over by noted Unitarian social reformer and educator Horace Mann. She sent such glowing reports of the school home that her parents relocated the whole family to Yellow Springs so the other children could benefit from the same fine education.

Rev. Antoinette Brown, Olympia's inspiration.

While at Oberlin, Brown invited Rev. Antoinette Brown (Blackwell) to speak and preach. As a young woman the then Antoinette Brown (no relation to Olympia, by the way) had struggled to become licensed to preach by the Congregationalists, was hired to serve a small New York church, and was irregularly ordained by a Methodist minister. She was a staunch abolitionist and suffragist who became a noted lecturer after her brief pastorate. Blackwell electrified the young Brown, “It was the first time I had heard a woman preach and the sense of victory lifted me up. I felt as though the Kingdom of Heaven were at hand.”

She determined to enroll in a theological school and pursue the ministry herself. That was easier said than done. No theological school in the country then regularly admitted women to degree programs, though a handful allowed them to take classes. Even such bastions of liberal theology as the Unitarian School of Meadville in Pennsylvania and Oberlin turned her down, although Oberlin said she could attend classes but “not participate in public exercises” or expect a degree.

She took a somewhat ambiguously discouraging letter from the president of the Universalist Divinity School of St. Lawrence University as an acceptance and surprised him by appearing for the 1861 term. Sheepishly, he had to admit her. It was characteristic of Brown’s bold determination. She afterward wrote, “I was told I had not been expected and that Mr. Fisher had said I would not come as he had written so discouragingly to me. I had supposed his discouragement was my encouragement.” Brown efficiently completed her course of study in 1863 with distinction.

Encountering resistance at every turn she doggedly convinced skeptical authorities to first ordain her, and then allow her to be called as a denominational minister. Shortly after graduation the St. Lawrence Association ordained her. After a period of pulpit supply preaching Brown was called as a minister to a Weymouth Landing, Massachusetts church. While serving there she became deeply involved in the organized women’s movement.

Antoinette Brown's sister in law, leading suffragist Lucy Stone recruited Olympia to rouse Kansas for a statewide referendum on giving women the vote.In the summer of 1867 Lucy Stone, the sister-in-law of her old inspiration Antoinette Brown, urged her to travel to Kansas to lead a campaign in support of a state constitutional amendment to extend the franchise to women. She arrived in the state to find no organization on the ground or any support. She had to schedule her own appearances, book halls, make traveling and lodging arrangements and then speak to often hostile audiences. Traveling relentlessly to all corners of the state she made over 300 speeches and attracted national attention. Although the state’s male voters overwhelmingly rejected the amendment, Susan B. Anthony commended her work as “a glorious triumph.”

Brown found herself in demand as a speaker but yearned to return to parish ministry. In 1870 she was called to the large, prosperous congregation in Bridgeport, Connecticut, the home church of active Universalist layman Phineas T. Barman. She found the church far less progressive than her first pastorate and, although she enjoyed support of the majority of members, a persistent minority campaigned against her in favor of calling a man.

During her service she married John Henry Willis in 1873. While on maternity leave with their first child, agitation by the minority to permanently replace her increased. By the end of 1874 she had enough and resigned her ministry. The family remained in Bridgeport and added a second child, but Brown—who kept her maiden name—searched for another pulpit.

She found one in Racine, Wisconsin on the shores of Lake Michigan just north of Illinois. The church was in “unfortunate condition” after a series of failed pastorates, was demoralized, and was struggling to maintain membership and keep afloat. Brown recognized that only churches in this condition were desperate enough to call a woman. She eagerly accepted the challenge. Her supportive husband closed his Bridgeport business to move with his wife. Eventually he became part owner of the local newspaper in Racine which not only helped support the family financially but gave support to Olympia’s ministry.

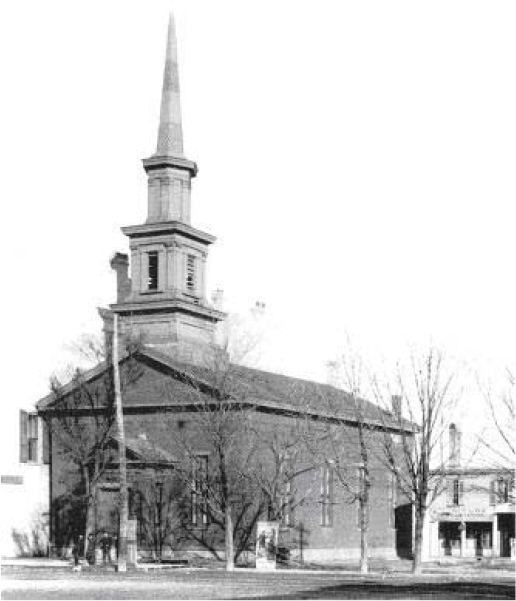

The Universalist Society of Racine, Wisconsin as it looked when Olympia served there.

Under her leadership the church flourished, grew in membership, stabilized its finances and became a cultural center for Racine. She sponsored regular speaking engagements by leading feminists and social reformers including Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Julia Ward Howe. After nine successful years at age 53 Brown decided to dedicate more of her time to the cause of women’s suffrage. The Racine congregation was on firm ground and continued to thrive. In the 20th Century the congregation took the name Olympia Brown Unitarian Universalist Church in her honor.

Brown continued to serve small Wisconsin Universalist congregations on a part time basis or as a pulpit supply preacher but spent most of her time as President of the Wisconsin Suffrage Association and as Vice-president of the National Woman Suffrage Association. She belonged to the Elizabeth Cady Stanton wing of the women’s movement which believed that reform on many issues in addition to obtaining the right to vote was essential for women’s equality. She was particularly concerned about educational opportunities for women and campaigned for previously all male schools to admit women—and to encourage women to dare to seek higher education.

By the 1890’s Brown was concerned that conservative leadership by Carrie Chapman Catt was sapping the strength of the movement. In 1913 she was happy to embrace Alice Paul’s new militant and confrontational Women’s Party. As a charter member she said, “I belonged to this party before I was born.” At the age of 80 she was delighted to take to the streets. She once burned Woodrow Wilson’s speeches in front of the White House because of his refusal to support suffrage. She risked arrest time and again.

After the 19th Amendment to the Constitution finally passed in 1919, Brown became one of the few veteran movement leaders to survive to cast her vote.

Olympia Brown at a suffrage convention in her old age. She was one of the few early leaders of the movement to survive to cast a vote in a Federal election.

Not content with that victory, she turned her energy to the peace movement becoming one of the founding members of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

In old age she summered in Racine and spent the cold months with a daughter in Baltimore, where she let her opinions be known on a number of issues. When she died there in 1926 at the age of 91 the Baltimore Sun wrote, “Perhaps no phase of her life better exemplified her vitality and intellectual independence than the mental discomfort she succeeded in arousing, between her eightieth and ninetieth birthdays, among the conservatively minded Baltimorans.”

The Olympia Brown Unitarian Universalist Church in Racine, Wisconsin continues her tradition of progressive, even radical social justice work. This very day the congregation is helping lead resistance to the Supreme Court decision voiding the Roe V. Wade decision and will be in a March for Roe at Monument Square in downtown Racine at 12 noon.

Brown’s body was returned to Racine where, after an overflow service at her old church, she was laid to rest next to her husband.

No comments:

Post a Comment