Although the statisticians tell us we do it in ever dwindling numbers, many of us are still off to church this Sunday morning—or

would be except for Coronavirus

precautions observed in many places and to various degrees. I have not stepped foot in my own church, the Tree of Life Unitarian Universalist Congregation in McHenry, Illinois since mid-March of last year. But I haven’t missed a Zoom service in all of that time until today when I ironically have

my second vaccine shot

scheduled. A lot of other folks have

Zoomed it as well. In fact our log-in attendance has actually been greater than our usual in-person services. Perhaps the pandemic will permanently

change how many of us worship

and how tightly tethered we will

remain to our brick and mortar temples.

Even before the emergency there was

an ongoing theological debate about

whether the church is the building or

the congregation. Let’s split the difference and say it’s both.

The buildings in which we gather

and worship tell us a lot about the folks

therein and perhaps their expectations

and hopes. Should the building be a hymn and monument to God, or should it be a humble house for the faithful? Christianity

has tugged us both ways.

Here are three takes on that.

Building Aix la Chapelle Grandes from the Chroniques-de-France

The 20th Century Welch poet John Ormond considered the masons and laborers who spent their whole

lives building temples that their grandchildren

might not see completed.

The Cathedral Builders

They climbed on sketchy ladders towards God,

with winch and pulley hoisted hewn rock into heaven,

inhabited the sky with hammers,

defied gravity,

deified stone,

took up God’s house to meet him,

and came down to their suppers

and small beer,

every night slept, lay with their smelly wives,

quarrelled and cuffed the children,

lied, spat, sang, were happy, or unhappy,

and every day took to the ladders again,

impeded the rights of way of another summer’s swallows,

grew greyer, shakier,

became less inclined to fix a neighbour’s roof of a fine evening,

saw naves sprout arches, clerestories soar,

cursed the loud fancy glaziers for their luck,

somehow escaped the plague,

got rheumatism,

decided it was time to give it up,

to leave the spire to others,

stood in the crowd, well back from the vestments at the consecration,

envied the fat bishop his warm boots,

cocked a squint eye aloft,

and said, “I bloody did that.”

—John Ormond

The American poet E. E. Cummings

was the son of noted and scholarly Unitarian

minister. In his youth he rebelled against his father and his

religion. Late in life he reconsidered and re-connected with Unitarianism.

It was during that period he wrote this.

I am a little church (no great cathedral)

i am a little church (no great cathedral)

far from the splendor and squalor of hurrying cities

-i do not worry if briefer days grow briefest

i am not sorry when sun and rain make april

my life is the life of the reaper and the sower

my prayers are prayers of earth's own clumsily striving

(finding and losing and laughing and crying) children

whose any sadness or joy is my grief or my gladness

around me surges a miracle of unceasing

birth and glory and death and resurrection:

over my sleeping self float flaming symbols

of hope and i wake to a perfect patience of mountains

i am a little church (far from the frantic

world with its rapture and anguish) at peace with nature

-i do not worry if longer nights grow longest;

i am not sorry when silence becomes singing

winter by spring, i lift my diminutive spire to

merciful Him Whose only now is forever:

standing erect in the deathless truth of His presence

(welcoming humbly His light and proudly His darkness)

—e. e. cummings

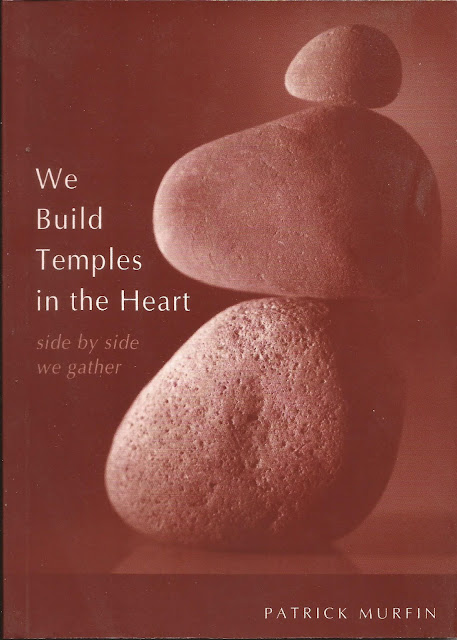

And finally, one from the Old Man, the title

poem in fact of my 2004 Skinner

House collection. This is the

original version, slightly longer than it appeared in the book

We Build Temples in the Heart

We have seen the great cathedrals,

stone laid upon stone,

carved and cared for

by centuries of certain hands,

seen the slender minarets

soar from dusty streets

to raise the cry of faith

to the One and Only God,

seen the placid pagodas

where gilded Buddhas squat

amid the temple bells and incense.

We have seen the tumbled temples

half buried in the sands,

choked with verdant tangles,

sunk in corralled seas,

old truths toppled and forgotten,

even seen the wattled huts,

the sweat lodge hogans,

the wheeled yurts,

the Ice Age caverns

where unwritten worship

raised its knowing voices.

But here, we build temples in our hearts

side by side we come,

as we gather—

Here the swollen belly

and aching breasts

of a well-thumbed paleo-goddess,

there the spinning prayer wheels

of lost Tibetan lamaseries;

mix the mortar of the scattered dust

of the Holy of Holies

with the sacred water

of the Ganges;

lay Moorish alabaster

on the blocks of Angkor Wat

and rough-hewn Stonehenge slabs;

plumb Doric columns

for strength of reason,

square with stern Protestant planks;

illuminate with Chartres’

jeweled windows

and the brilliant lamps of science.

Yes here, we build temples in our hearts,

side by side we come,

scavenging the ages for wisdom,

cobbling together as best we may,

the fruit of a thousand altars,

leveling with doubt,

framing with skepticism,

measuring by logic,

sinking firm foundations in the earth

as we reach for the heavens.

Here, we build temples in our hearts,

side by side we come,

a temple for each heart,

a village of temples,

none shading another,

connected by well-worn paths,

built alike on sacred ground.

—Patrick

Murfin

No comments:

Post a Comment