More than 60,000 bodies crammed into Chicago’s

Soldier Field, then the seating

capacity of the stadium on the Lake 55 years ago on Sunday, July 10, 1966. The

Sun-Times

reported the next day that thousands

more were turned away. Although mega-watt

stars were on hand to perform including Mahalia Jackson, Stevie

Wonder, and Peter Paul & Mary not a single ticket

was sold to see them. The real star, you see, was the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and he had

something important to say

that day—a challenge to the City of Chicago for specific

and systematic change to make African-American

citizens truly equal in a great Northern

city.

The waves of change caused by that day continue to lap the shores of Lake

Michigan.

In 1965 with a string of impressive victories for its relentless non-violent protest campaigns across the South and Civil Rights Act

of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of

1965 under its belt, the Southern

Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

began to cast its eye to the

great northern cities where the Great

Migration had established huge populations of the Black Diaspora to see if the tactics of non-violence and civil disobedience could successfully be applied

outside of Dixie. No American city was a more important destination and home for

Blacks than Chicago—and none so completely segregated in housing

and by neighborhood.

The city already had active and well

known groups employing non-violent protest to pressure City Hall for changes. The Coordinating Council of Community

Organizations (CCCO) had its

roots in protests to school policies under Superintendent of Public Instruction

Benjamin Willis in the early ‘60s. A

campaign of sit-ins and two mass attendance boycotts were aimed at the de-facto segregation of the public

schools. Teacher Al Raby came to leadership of the loose organization that included sometimes quarrelsome elements including militants

of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Chicago Area Friends of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the more moderate

Chicago Catholic Interracial Council

and the Chicago Urban League.

The Quaker American Friends

Service Committee (AFSC) was

also active on the West Side, the poorest of Chicago’s

ghettos and often ignored even by older established Black groups based

in older South Side communities.

But despite the White anguish, the Black community was

becoming too large, too noisy, and, yes, too dangerous to be ignored.

The AFSC anti-slum symbol and button were used by the Freedom Movement.

The SCLC’s Director of Direct Action James Bevel came north in ’65 to work

with the West side project and was soon also in contact with Raby who wanted to

launch a new campaign against housing discrimination. With the blessing of Dr. King, the SCLC committed its resources to the

new effort dubbed the Chicago Freedom

Movement. Bevel and a handful of

other veteran SCLC activists moved to the city to launch the project.

The Chicago Freedom Movement declared its intention to end slums in the city. It organized tenants’ unions, assumed control of a slum tenement, founded action groups like Operation

Breadbasket, and attempted to rally both Black and white citizens to support its goals. The campaign

created an uproar and attracted widespread publicity but was not moving Mayor Richard J. Daley and the establishment

he represented to make any concessions. Very reluctantly Raby agreed to let Bevel call in the big gun—Dr. King himself.

For King this was an

opportunity he had been looking for. He had wanted for some time to turn his attention to economic issues and the systematic

racism that constrained Black

ambitions everywhere, not

just in the South. And he wanted to challenge the complacency of white liberals who gave lip service to the cause as long as it was not on their doorstep.

In January of ’66 King very publicly moved his family into a slum apartment on the West Side.

He announced his intention to stay in the city and launched a new

round of marches and protests. Just as

Raby had feared, King became the face of the movement, an eight-hundred-pound-gorilla in the media that left little room for established local leaders.

Rev. King and Coretta Scott King wave from the window of the Lawndale apartment they moved into in January. In the window on the were his SCLC associates Andrew Young and James Bevel.

And as he must have expected, the city’s press, which had once painted him a hero for freedom in the South,

now frothed in unison that he was a

dangerous outside agitator disturbing racial harmony, provoking violence, and likely fronting

for more shadowy radicals and Communists.

By spring it was apparent

that vague or ad hoc demands were not enough. At a series of participatory democracy meeting conducted by the CCCO, the Quakers

on the West Side, and the new Operation Breadbasket, the project of rising star the Rev. Jesse Jackson, ideas were gathered, refined, and sent back for

review and revision. In the end a list of twelve demands was

drawn up addressed to six power centers in the city.

The question then was how best to present the demands to most

dramatically get the attention of

authorities and to mobilize even greater participation in the direct action campaign—a rally,

a march on City Hall, an address to an important civic organization like the Union League which represented

the establishment, a press conference, even the launch of a hunger strike were all considered.

In the end leadership of the

campaign settled on a unique stunt

followed by the kind of mass rally of thousands where King’s legendary oratorical skills would rouse the Black community and White

allies to action.

The big event required a scramble to organize. Money,

always a problem, needed to be raised, and this time donations from white liberal were

drying up. There were tricky negotiations with the Park District, which was under the firm control of Daley loyalists, for use of Soldier Field. Neighborhoods

across the city had to be organized and transportation for tens of

thousands to the rally site arranged.

The press had to be alerted and as much as possible massaged.

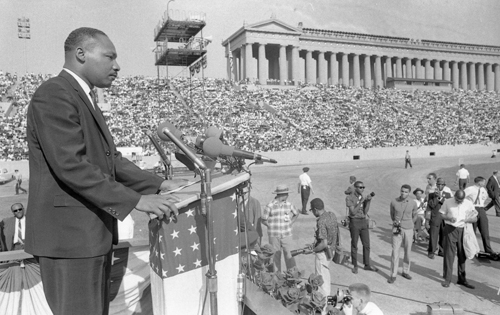

Rev. King did a lap in an open car to kick of the Soldier Field rally.

When he arrived at the stadium for

the mass rally, King entered in an open convertible which drove around the cinder outer

track before the bowl of cheering supporters. In his

speech, King laid out the reason for the demands and campaign.

We are here today because we are tired. We are tired of

being seared in the flames of withering injustice. We are tired of paying more

for less. We are tired of living in rat-infested slums and in the Chicago

Housing Authority’s cement reservations. We are tired of having to pay a median

rent of $97 a month in Lawndale for 4 rooms while whites in South Deering pay

$73 a month for 5 rooms.

We are tired of inferior, segregated, and overcrowded

schools which are incapable of preparing our young people for leadership and

security in this technological age. We are tired of discrimination in

employment which makes us the last hired and the first fired. We are tired of

being by-passed for promotions while supervisory jobs are granted to persons

with less training, ability, and experience simply because they are white. We

are tired of the fact that the average white high school drop-out in Chicago

earns more money than the average Negro college graduate.

We are tired of a welfare system which dehumanizes us and

dispenses payments under procedures that are often ugly and paternalistic. Yes,

we are tired of being lynched physically in Mississippi, and we are tired of

being lynched spiritually and economically in the North.

We have also come here today to remind Chicago of the fierce

urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to

take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the

promises of democracy. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all

of God's children. Now is the time to end the long and desolate Night of Slumism.

Now is the time to have a confrontation in the city of Chicago between the

forces resisting change and the forces demanding change. Now is the time to let

justice roll down from city hall like waters and righteousness like a mighty

stream….

And, in the face of increased

criticism of his strict commitment to non-violence by growing numbers of

militant Black Power advocates, King

reiterated his commitment:

I understand our legitimate discontent. I understand our

nagging frustrations. We are the victims of a crisis of disappointment. But I

must reaffirm that I do not see the answer to our problems in violence. Our

movement's adherence to nonviolence has been a major factor in the creation of

a moral climate that has made progress possible. This climate may well be

dissipated not only by acts of violence but by the threats of it verbalized by

those who equate it with militancy. Our power does not reside in Molotov

cocktails, rifles, knives and bricks. The ultimate weakness of a riot is that

it can be halted by superior force. We have neither the techniques, the numbers

nor the weapons to win a violent campaign.

Many of our opponents would be happy for us to turn to acts

of violence in order to have an excuse to slaughter hundreds of innocent

people. Beyond this, violence never appeals to the conscience. It intensifies

the fears of the white majority while relieving their guilt.

No, our power is not in violence. Our power is in our unity,

the force of our souls, and the determination of our bodies. This is a force

that no army can overcome, for there is nothing more powerful in all the world

than the surge of unarmed truth…

…Nonviolence does not mean doing nothing. It does not mean

passively accepting evil. It means standing up so strongly with your body and

soul that you cannot stoop to the low places of violence and hatred. I am still

convinced that nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon, it cuts without

wounding. It is a sword that heals, here in Chicago we must pick up the weapon

of truth, the ammunition of courage, we must put on the breastplate of

righteousness and the whole armor of God. And with this, we will have a

non-violent army that no violent force can halt and no political machine can

resist.

Later in the meeting Floyd McKissick, President of CORE, a proponent

of Black Power, and sometimes

a harsh critic of King,

stepped to the microphone to assert that in this case CORE was in complete agreement with not only the aims of the movement, but the strategy

of non-violent protest.

After the rally King left the

stadium. In front of a large crowd and

with TV film cameras grinding, King took

advantage of a reference to his historical namesake and symbolically

nailed the Freedom Movement demands

on the doors of City Hall. The demands were:

Real Estate

Boards and Brokers

Public statements that all listings will be available on a

nondiscriminatory basis.

Banks and

Savings Institutions

Public statements of a nondiscriminatory mortgage policy so

that loans will be available to any qualified borrower without regard to the

racial composition of the area.

The Mayor

and City Council

1.

Publication of headcounts of whites,

Negroes and Latin Americans for all city departments and for all firms from

which city purchases are made.

2.

Revocation of contracts with firms

that do not have a full scale fair employment practice.

3.

Creation of a citizens review board

for grievances against police brutality and false arrests or stops and

seizures.

4.

Ordinance giving ready access to the

names of owners and investors for all slum properties.

5.

A saturation program of increased

garbage collection, street cleaning, and building inspection services in the

slum properties.

Political

Parties

The requirement that precinct captains be residents of their

precincts.

Chicago

Housing Authority and the Chicago Dwelling Association

1.

Program to rehabilitate present

public housing including such items as locked lobbies, restrooms in recreation

areas, increased police protection and childcare centers on every third floor.

2.

Program to increase vastly the

supply of low-cost housing on a scattered basis for both low and middle income

families.

Business

1.

Basic headcounts, including white,

Negro and Latin American, by job classification and income level, made public.

2.

Racial steps to upgrade and to

integrate all departments, all levels of employments.

It was a sweeping and ambitious agenda that demanded concessions from every aspect of the power structure.

The renewed campaign kicked off with

a focus on open housing demands, protests in front of real estate offices across the city, and marches into white neighborhoods. These

marches were often greeted with jeers—and sometimes violence—by neighborhood residents,

most famously in Marquette Park

where marchers were showered with bottles, bricks, and stones with little interference from

the police. King himself suffered a minor head wound.

These marches saw the support of white liberals dwindle. Among the

first to bail out was the Catholic Archdiocese. Although many individual priests, nuns, and lay people continued to stand by King and march with the movement,

the Church withdrew its support while marchers strode

through the heart of their ethnic parishes. The editorial

pages of the city’s great newspapers denounced the marches as dangerous provocations and blamed

the ensuing violence not on angry

white mobs, but on the non-violent

marchers.

The second aspect of the Movement’s

drive was the inauguration of a series of summit

meetings with civic leaders to

lay out the demands and open

negotiations for accommodation. Some of the first of these were with the Chicago

Board of Realtors. But even these

meetings were denounced in the press

as thinly veiled extortion.

To his dismay, King saw his dream of

Whites and Blacks coming together for justice evaporating in front of

his eyes. The city grew more racially polarized day by day and the phrase White backlash entered the language.

Some

authorities were willing to strike at least symbolic deals. After yet another march, this time in South Deering on August 21, was attacked by a white mob, movement

leaders and local politicians arranged the Summit

Agreement. King agreed to

halt marches into all-white neighborhoods and

to postpone indefinitely the planned

march in Cicero. In exchange, the

city agreed to far-reaching guarantees for open housing for African

Americans.

Despite pleas by King and Bevel,

CORE defiantly went ahead with a march

in the all-white ethnic suburb of Cicero in September with about 1,500

participants. The marchers were,

predictably mobbed and mauled. Despite the protestations of the Freedom Movement that they had nothing

to do with the CORE march, they were blamed

anyway.

The terms of the Summit Agreement,

even those resulting in

new ordinances by City Hall, made little actual and practical difference to the lives of ordinary Black

Chicagoans. Raby, who felt snubbed and ignored by King and

Bevel, resigned from the CCCO, which soon ceased

to function. However, the new

Operation Breadbasket stepped up and continued to press for the goals of the

Movement gaining power and influence over the years and making Jesse Jackson a major national figure in his own right.

King and Bevel left the city. They were disappointed. King considered the campaign largely a

failure and was stung by harsh criticism not just from

liberal whites, but from the increasingly influential Black Power

movement. He turned increasingly to anti-Vietnam protests over the next two

years as he planned a major push on economic injustice

he called the Poor People’s Campaign which

he hoped would re-unite Blacks, whites, Latinos,

and Native Americans in a common cause. Preparations for that campaign were put on

hold for the Memphis Garbage Strike and

King’s assassination.

In Chicago, the conditions that gave

rise to the Freedom Movement boiled over

in the West Side Riots of 1967 and

the riots following King’s assassination in 1968.

A voting registration and get-out-the-vote off-shoot of the

Freedom Movement led by the SCLC’s Hosea

Williams helped set the stage for

the rise of Black political power in the city and for the eventual election of Mayor

Harold Washington.

All part of the legacy of the meeting at

Soldier Field.

But, by the way, Chicago remains the most residentially segregated city in the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment