In the eyes of anti-war folks opposition to the Draft is a matter of principle. I fully

understand. After all, I was a Vietnam resistor and did my time in Federal custody. The active

draft was allowed to expire un-mourned though

a rusty Selective Service System remains in place if needed. Our recent wars of choice—the Gulf War,

intervention in Bosnia, and the tandem wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—have

been fought by an all-volunteer

professional military and a National

Guard/Reserve component stretched

to the limits. As always, the dead young soldiers are mostly from the poor

and working classes. The sons

and daughters of the economic and political elite are notable

by their almost complete absence. Yet few, if any, voices have been raised for a return to the Draft.

The nation’s first Draft, enacted in the midst of a bloody Civil War did not get off to a good start and

its opponents hardly covered themselves in progressive glory. On July 13, 1863 the New York Draft Riots broke out.

Historians describe it as the

largest and bloodiest revolt against government authority in American history—except for the bloodier conflict that sparked it.

In the third year of carnage,

the Union desperately needed fresh

bodies. The enthusiastic responses that had filled the ranks of Volunteer units in the early days of the war had faded with the mounting casualty

count. After the first batches of 90 day volunteers

came and went, subsequent volunteers units found themselves serving “for the duration.” As mounting casualties thinned their ranks with no good system of recruiting replacements, regiments shrank to the size of companies, brigades to regiments, divisions to brigades. Raising

new volunteer units at home

became harder and harder.

President

Abraham Lincoln, knowing how unpopular it would be, reluctantly

backed the Draft in the hope that the threat

would spur a new round of volunteer enlistments. It turned out it did, but that’s another

story. Democrats were ideologically

opposed to the extension of government power and many were either tepid supporters of the war or in sympathy with the South. Even many Republicans were queasy.

But the Draft, though unpopular, might have been tolerated if it were not for one glaring provision. Drafted men could escape service if they provided—hired—a substitute or

paid the Treasury a $300 commutation fee. This

provision was intended to produce an infusion of cash in support of the war effort which was seen as just as important as securing bodies. Naturally members of the lower classes resented this, recognizing that rich men’s sons could buy their way out of harm’s way

while they were doomed to be cannon fodder.

Many of New York’s laboring classes

had another reason to

resent conscription. The war effort had stimulated the economy. Factories

and ship yards were humming with war production. Unemployment, long the bane of the slums, was disappearing and wages were high. To a lot of working men it looked like just when they were finally going to get a piece of the pie, they were

going to be snatched away to become $8 a month privates.

Democrats

in

control of the city had been allied with Southern Democrats since Aaron

Burr and the earliest days of Tammany Hall. They competed against Whig/Free Soil/Republican organizations

from Up State for control of the state government. In 1862

with state Republican boss William H. Seward away

serving in Lincoln’s Cabinet, New

York Democrats were able to elect

anti-war Horatio Seymour as Governor, who the Lincoln administration viewed as a Copperhead and a virtual

fifth columnist.

Tammany

Hall Machine rallied opposition to the Draft,

although they were careful not to call for resistance. Instead they proposed to pay the fees of members who were drafted. But they indirectly

contributed to opposition with their successful campaign to enroll as many immigrants as possible as citizens

so that they could vote. These new citizens, largely but not exclusively Irish, found themselves suddenly subject to the Draft.

The first Draft drawing occurred on Saturday, July 11 without incident. But when

the list of drafted men was published

in Monday’s newspapers it overwhelmingly contained

the names of laborers and mechanics. It looked like

the “rich man’s war and poor man’s fight” that opponents had warned of.

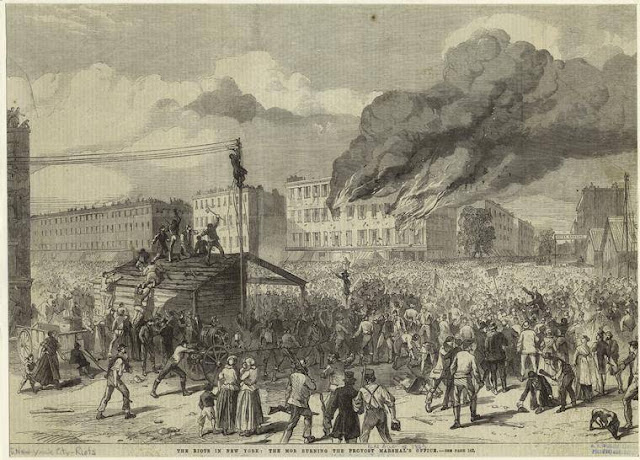

The second drawing was slated to

take place on Monday, July 13 at 10 am at the Ninth District

Provost Marshal’s Office, Third Avenue and 47th Street. A crowd of over 500 gathered outside led by firemen of Black Joke Engine

Company 33, some of whose members had been called. After pelting

the building with paving stones,

they rushed inside beating and dispersing officials then setting

the building ablaze.

The undermanned Police Department responded

but was unable to

contain the crowd. Superintendent

James Kennedy was recognized,

although in civilian clothes, and

was seized by the crowd which nearly beat him to death. The police responded with a disorganized charge with clubs and revolvers but were overwhelmed by the growing mob which began to roam the streets seeking new targets for its wrath. The local

armories of the New York Militia were

empty because their troops had been sent to Pennsylvania to stem the tide of Robert E. Lee’s invasion.

The Police, for the time being, were on their own.

The famous Bulls Head Hotel on 44th Street was torched when it refused to

serve rioters liquor. The home of Republican Mayor George Opdyke on Fifth

Avenue, the Eighth and Fifth District police stations, and other buildings were attacked and set on

fire. The staff of Horace Greeley’s Republican newspaper, The Tribune barely managed to save their building by manning two Gatling Guns

that they had somehow procured.

The mood of

the crowd really turned ugly when they encountered a Black man on Clarkson

Street. He was beaten, hanged from a tree and set afire by

the cheering mob. Blacks of all ages and both sexes were attacked when found, their homes burned by laborers resentful

of competition with them for jobs and blaming them for causing the War. The Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue was set ablaze although

hard-pressed police reportedly were able

to evacuate the nearly 400 orphans and the staff. In all at least 26 Blacks were killed, although many historians regard that figure as ridiculously

low.

As night fell the police finally established a line preventing the rioting from spreading south of Union Square. Then heavy rains helped douse the fires and send

everyone home.

The crowd

swelled again on Tuesday as many workers not involved on the first day downed their tools and joined, paralyzing business

and commerce. The homes of several prominent Republicans

were sacked and burned. Governor

Seymour arrived from Albany and addressed

the crowd at City Hall declaring that conscription was

unconstitutional. Seymour’s defenders have said that his motivation was simply to diffuse the situation. In Washington Lincoln and the War Department considered it pandering to the mob at best or inciting

an insurrection—and possibly a wider

Copperhead rebellion. They scrambled

to mobilize troops from Pennsylvania

to march to the relief of the city. Meanwhile Major General John Wool, an aging

Mexican War veteran in command of the New York District cobbled together a force

of 800 troops from the harbor forts and West Point and ordered the New

York Militia home from the front.

The announcement in the newspapers on

Wednesday by the Provost Marshall

that the draft would be suspended in the city caused some rioters to stay home. Others returned to the streets and the rampage.

Militia and

Volunteer units who reached the city, often exhausted by forced marches and irate at violence at home while they were facing

the enemy—many of them having just

seen hard action at Gettysburg—reacted harshly and without restraint. They unleashed

volleys of fire into mobs, charged with bayonets, and even

cleared public squares with artillery fire, some of it incoming

from Navy ships in the harbor. Among the troops arriving from

the battlefield were members of 11th New

York Volunteers (who had begun the

war as Ellsworth’s Zouaves recruited from the same fire battalions now

leading the rioters), the 152nd

New York Volunteers, the 26th

Michigan Volunteers, the 30th Indiana

Volunteers and the 7th Regiment New

York State Militia.

Governor Seymour under pressure from Washington also dispatched

Upstate Militia units that had not

yet been Federalized.

Many of the troops from the City were

Irish, as were substantial numbers of the rioters. Even in the face of such overwhelming force, fighting was sometimes heavy. Colonel Henry F. O’Brien, commanding the 11th was seized by the

mob and beaten to death.

By Thursday

there were several thousand troops in the city.

That evening a final

confrontation near Gramercy Park was

quelled with artillery fire resulting in scores of deaths. After that

an uneasy peace prevailed in the city.

The exact toll of deaths and injuries in four

days of rioting is a matter of wide debate. Respected Civil War historian James M. McPherson places the total

civilian deaths at a relatively light 120 while Herbert Asbury, a specialist

in New York history and expert

on the 19th Century gangs who played

a leading role in the fighting, places the figure much

higher with as many 2,000 killed and 8,000 injured.

Samuel Eliot Morison, author of one of the most respected single volume histories of

the United States ever written and a Boston Yankee with unabashed Union sympathies regarded the riots as, “equivalent to a Confederate victory.”

Lincoln and the War Department

considered it a very close thing, but in the end a victory. Not only was the Draft resumed without further interference, but

widespread public revulsion in the North doomed Copperhead

hopes in Ohio and border regions.

Property

losses were estimated to be between $1 and 5 million. Most of that loss was uncompensated by insurance

or the government. At least 50 buildings burned, including two Protestant churches with noted Abolitionist

ministers.

The Draft Riots are often painted as an exclusively Irish uprising. While the Irish certainly made up large portions of the mobs, they were never even in the majority. Plenty of lower class “Americans,” including members native Yankees of the Fire Brigades that played such a prominent role on the first two days, were involved as were other immigrant nationalities—except for the stalwart Unionist Germans. And, as we have seen, Irish in the police and military played key roles in finally quashing the rebellion.

No comments:

Post a Comment