I am

more than thrilled to learn that my old friend, Fellow Worker,

and mentor Carlos Cortez will be honored Sunday, September 19 as

one of four inductees into the Chicago Hall of Literary Fame in a ceremony

at the Cit Lit Theater, 1020 West Bryn Mawr Avenue from 7

to 8:30 pm.

Carlos

might not we well known to the general public, but he is a revered

figure in the labor movement, especially with the Industrial

Workers of the World (IWW) and in the Latinx and Native

American arts communities. He was perhaps

best known for his lino and woodcut posters and illustrations.

For him art of all types was inseparable from social activism and

was meant to be easily accessible to ordinary people. He could have made a fortune and been

far more widely recognized as a fine artist if he sold his posters in signed

and numbered editions.

Instead, he printed them himself in unlimited numbers by silk

screening on what ever paper stock he could scrounge and were sold

for a few dollars or more likely given away.

In fact, if he discovered there was a commercial market for his prints

that were being re-sold by dealers and galleries, he would print

more just to keep the price down.

Much of his work has been archived, preserved, and displayed

and displayed at Chicago’s National Museum of Mexican Art, which he

helped nurture.

But

he is being recognized now as a writer.

He was also a roll-up-his-sleeves, plain spoken poet who published

three collections in his lifetime who shared his work at poetry

readings and slams around the city avoiding the establishment

to find venues where the excluded and outcast could be included. He performed his pieces at union

meetings and on picket lines, at rallies and benefits,

and for those who gathered in the informal salon he kept open in the former

Northwest Side neighborhood storefront where he made a home with his beloved

wife Marianna.

Most

of his work first saw print in the Industrial Worker with which

he was associated for more than 40 years.

Born

in Milwaukee on August 13, 1923 to a German Socialist mother and

a Mexican indio/mestizo IWW member Father. He was steeped from the beginning in working

class culture and revolutionary values. He took seriously the old Socialist

admonitions not to allow governments to divide workers and turn

them against each other in imperialist wars. During World War II he refused

induction into the Army and spent nearly three years in the Federal

Prison at Sandstone, Minnesota—ironically the same prison

where I was held for the same offense for draft resistance during the Vietnam

War. After the war he worked

in various factories.

In

the late 1950’s he decided to come down to Chicago to become more involved with

the IWW where there was both an active general membership branch and the

union’s General Headquarters. He

volunteered his time helping out at GHQ where Fred W. Thompson

then the Editor of the Industrial Worker began to use his

contributions of both illustrations and writings.

Soon

he was contributing several pieces each issue—articles, essays, folksy

polemics, and occasional verse. Short musings, observations, and yarns were

printed as a regular feature column The Left Side. Other pieces appeared signed as CAC,

C.C. Redcloud, Koyokuikatl, and his IWW membership card number

X321826.

When

he first came down he was still known as Karl Cortez as his mother

called him, but has he immersed himself in the city and connected to the

Mexican and Chicago communities, he became Carlos and adopted the

big hats, and flowing moustache and sometimes goatee which became his

trademark.

By

the late 60’s Carlos took over as editor of the paper and in 1970 I began my

regular contributions to its pages.

Later we reorganized the staff as collective and

eventually I assumed the editorship while Carlos continued his

contributions. When we lost office space

to do the layout and production, we did it at a table in Carlos and Marianna’s apartment. When that place was remodeled by their

landlord they stayed with me and then Secretary Treasurer Kathleen Taylor in our near-by fourth floor

walk-up apartment in the building dubbed Wobbly Towers for a few

months.

Meanwhile

Carlos and I both worked as custodians at Coyne American Institute,

a trade school on Fullerton Avenue. A few years later when I was homeless Carlos

returned the favor and I stayed with them for some time enjoying Marianna’s

strong espresso in the morning and hanging with Carlos over Wild Turkey in

the evenings in the large gallery-like front room that served as his workshop

and gathering spot. Almost any evening

was an education.

It is

really a tribute to the Industrial Worker as a working class

institution that Carlos is being honored for the work that largely first

appeared there.

During

those years Carlos became a founding member of the Movemento Aristico

Chicano (MARCH)—the first organization of Latino artists in

the city. With his close friend Carlos

Cumpián and others meeting in the comfortable front room, he built an

organization which mentored many young artists, spread “the culture”,

and helped foster the re-birth of the muralist movement in the

city. He also became an early supporter

of the Mexican Fine Arts Center now known as the National Museum of

Mexican Arts which became the repository of many of his works and has the

largest collection of his extensive production in the world. He was also active with the Chicago Mural

Group, Mexican Taller del Grabado (Mexican Graphic Workshop), Casa

de la Cultura Mestizarte, and the Native Men’s Song Circle, a Native

American group out of the American Indian Center. Through that association, he came to mentor

and encourage young Indian artists with the same passion he dedicated to the

Chicanos. In fact, there was no artist

or poet of any race who was not welcome in that home, as long as they were

ready and eager to serve the people’s needs and not “art for art’s sake,”

a notion he found repugnant and elitist.

A lifelong

bachelor, in the early 60’s a Greek friend told him that he should

meet his sister. The trouble was

that she was still in Greece. The two corresponded

through her brother for a while.

Carlos saved his money, quit his job, and crossed

the ocean as a passenger on a freighter. He met Marianna Drogitis, a lovely

young woman who was, however, by the standards of her culture, a spinster having

rejected several suitors.

The two fell in love despite not speaking a word of each

other’s language. They communicated

by gesture and the few words of German they had in common—she had

learned the language in occupied Greece where members of her family were

active in the Resistance. They

returned to the U.S. on another freighter, married, and settled into the happiest

marriage I have ever seen in a Chicago apartment in 1965.

When

I proposed to Kathy Brady-Larsen in the early 80’s, Carlos was

pleased to make a drawing of the two of us with her daughters

Carolynne and Heather for the invitations I designed. He and Marianna danced happily at our

wedding party at Lilly’s on Lincoln Avenue.

By

1981 Carlos’s heart forced him to retire from wage slavery. It gave him more time to dedicate to his artwork,

poetry and causes. Unfortunately, it

also put a strain on Marianna who took extra work to make up for the

lost income. Despite sometimes working

twelve hours at two jobs, she always had a smile for any of Carlos’s many

guests, and a pat on the cheek for the old man.

Carlos,

although best known as a graphic artist and for his work on the Industrial

Worker, was also a poet. He would do

occasional readings at an old haunt, the College of Complexes, in coffee

houses, at radical bookstores, and wherever his friends

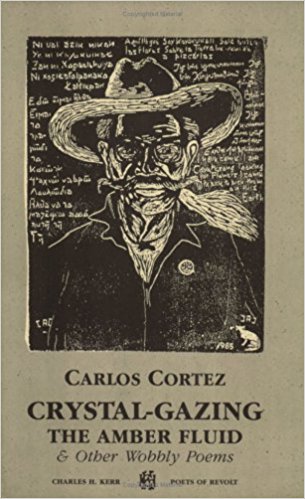

gathered. He wrote three books of

poetry, including De Kansas a Califas & Back to Chicago,

published by March/Abrazo Press, and Crystal-Gazing the Amer Fluid

& Other Wobbly Poems, published by the old Socialist publisher Charles

H. Kerr & Company. Carlos was President

of the Kerr Board for 20 years, a title he detested. He also edited, wrote the introduction

to, or contributed to several other books.

Carlos

was devastated when his beloved Marianna died in 2001. I last saw him at her memorial.

His health

deteriorated rapidly after that, and he was often confined to a wheelchair. He continued to greet a steady parade of

visitors and admirers to his studio home and participated in the planning of

new exhibitions of his work, including one in Madrid sponsored by the anarcho-syndicalists

of the Confederacion National de Trabajo (CNT.) He suffered a massive heart attack and

was confined to his bed for the last 18 months of his life.

On

January 17, 2005 Carlos died, surrounded by friends and “listening to the music

of the Texas Tornados.”

His

long-time friend Carlos Cumpián will speak about him at the Hall of Fame

induction ceremony.

The Chicago

Hall of Literary Fame describes its mission thusly:

Chicago is not a

city that can be crisply explained, neatly categorized, or easily understood.

Yet through our

literature we strive to define our place in the world. Our literature speaks to

our city’s diversity, character and heart. In our literature can be found all

we love and hate, frozen snapshots of our vast terrain over the years,

commentary on our ever-changing culture. In our literature can be found who we

are and what we do and where we do it. The value and character of our city is

not only reflected in but shaped by our great books.

Our mission is to

honor and preserve Chicago’s great literary heritage.

Unlike

other cultural institutions the Hall of Fame does not just honor world

famous authors but takes pains to highlight authentic and diverse

voices.

Other

honorees this year include Black novelist Frank London Brown whose work

describing life in the Projects in the late 1950’s included novel Trumbull

Park and the short story McDougal. He was also a machinist, union organizer,

and was director of the Union Leadership Program at the University

of Chicago. He enjoyed some fame

as a jazz singer as appearing with Thelonius Monk. Brown died

young in 1962. Jeannette Howard Foster

was an educator, librarian, translator, poet, scholar,

and author of the first critical study of lesbian literature, Sex

Variant Women in Literature in 1956. She was also the first librarian of

Dr. Alfred Kinsey’s Institute for Sex Research, and she influenced

generations of librarians and gay lesbian literary figures. She died in 1981. Gene Wolf was a science fiction

and fantasy writer noted for his dense, allusive prose as

well as the strong influence of his Catholic faith. He has been called the

Melville of science fiction. Wolfe is best known for his Book of

the New Sun series—four volumes, 1980–1983—the first part of his Solar

Cycle He died in 2019.

Carlos

will be in good company.

No comments:

Post a Comment