The story

goes like this. Stone mason and sometimes preacher

Marinus of Arba and his life-long

pal Leo were forced by some political

upheaval to leave their home of Rab, a Roman colony on

the island of Arba in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of what is

now Croatia. The two young men settled in the northern

Italian city of Rimini to find work reconstructing the city’s ruined walls.

But there they ran afoul

of the infamous persecution of

Christians ordered by the Emperor Diocletian

and had to flee the city.

At

the same time some of Marinus’s sermons as

an ordained Deacon were found

somehow at odds with the not-yet codified tenets of the Church so

he could find no refuge. The pair fled to the rugged, remote, and unpopulated Apennine Mountains determined to live as monastic hermits equally free of the

Emperor and the Pope. By tradition

on September 3, 301 CE Marius began

laying the stones of a chapel and

the establishment of a monastic

community.

A much later German etching depicting Saint Marinus the Stone Cutter building his monastery.

Marinus died many years later in 366 with

the words Relinquo vos liberos ab utroque homine—I leave you free from

both men—meaning the Emperor and the Pope.

By then his community had grown and prospered and the monastery high on

the top of Monte Titano had become a

haven for refugees persecuted

by both. It would remain so through the centuries.

Eventually

Marinus would be canonized as San Marino and the community that

sprang up around his Hermitage would become known as the Most Serene

Republic of San Marino. The tiny nation, occupying less than 24 square miles, has maintained its independence

ever since and celebrates September 3 not only as Marinus’s Feast Day,

but as foundation date of the Republic.

That makes San Marino easily the oldest surviving continuously sovereign state in the world, and because it never came under the rule of even a local nobleman or feudal governance by the Abby, also the oldest Republic. This was made possible by its isolation, the terrain so rugged that

it was said there was hardly a square

inch of level ground, location away from traditional trade routes and invasion

corridors, sometimes surprising

friends in High Places, and just

plain dumb luck.

In

its earliest years San Marino was informally ruled by the hermit monks of Church of St. Agatha on the top of

Monte Titan. This hardly was governance

of any meaningful kind. In the

early 400’s with Rome near collapse eight neighboring towns joined with

San Marino seeking protection from invading Goths. These communes became

the along with the original settlement became San Marino’s nine municipalities. With the expanded territory and population, the heads of families established themselves as ruling council known

as the Arengo which governed

from the 5th Century to 1243. By

then it had grown to representatives of more than 50 extended families and had

become a cumbersome body and was riven by feuds and rival

cabals.

The Sammarinese,

as citizens

are known, fed up by oligarchic rule

established their own Grand and General Council which Pope

Innocent IV, the titular head of

state, in one of the first acts of

his Papacy, recognized as the

country’s ruling body. Every six months

the Grand and General Council elected two Captains

Regent to co-hold executive power. They were not eligible for re-election, but could be returned to

the position on later occasions.

Traditionally the pair of Regents were drawn from opposing factions on the Council and since the adoption of a two party system, from each of the

political parties. This form of

governance was molded after the Senate and

Consuls of the old Roman Republic. This arrangement was codified the Leges

Statutae Republicae Sancti Marini—Constitution

of San Marino—recorded in a series of

six books written in Latin in

the late 1600. In 1631the Papacy waived its light

claims on San Marino and recognized its independence from the Papal

States.

The Constitution of San Marino was codified and published in 1600.

If

maintaining essential independence for nearly 1400 years from the declining years of the Roman Empire,

through the Dark Ages, and the Renaissance when intrigue and war spread

across the Italian Peninsula as the

Papacy, ambitious city states, and

various leagues and alliances struggled for supremacy was

hard, the challenges of the Napoleonic

era, clash of Empires, and the rise of the European nation state was even more daunting.

In

1797 San Marino’s independence was threatened when Napoleon Bonaparte’s French Army was rampaging through Italy. Somehow Antonio

Onofri, one of the two serving Captains Regent,

managed to befriend the General and impress

him with his tale of San Marino’s long independence as a republic. Napoleon at this stage of his career was

still an ideologically committed Republican himself. Not only did he offer to guarantee and protect San

Marino’s independence, but he offered to award the country territory from

adjacent states. The grateful Grand and

General Council politely refused that off rightly fearing that accepting

a land grab would alienate more powerful neighbors and lead

to attacks when the French would inevitably eventually leave Italy.

An

even greater challenge was the long struggle of Italian unification that began after the final fall of Napoleon and

the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and

continued up to the final surrender of the Papal States and the location

of a capital at Rome for the Kingdom of Italy. San Marino began the period completely

surrounded by the Papal States. But in

1859 the rapidly expanding Kingdom of

Sardinia extended its borders over Central

Italy and San Marino lay astride the border between that Kingdom and the

Papal States. In accordance to its

traditions, San Marino became of place of refuge for many fleeing the fighting,

but especially for refugees from pro-unification

areas. In December 1860 the Papal province of Marche adjacent to San Marino was

incorporated in the Kingdom of Sardinia.

That

made San Marino an island in an area aflame for unification. In gratitude

and in recognition of the tiny nation’s long resistance to Papal rule, unification

leader Giuseppe Garibaldi prevailed

upon the soon-to-be King of Italy,

Victor Emanuel II who had led the Sarndinian-Piedmontese

forces which had captured Marche, to respect the traditional independence

of San Marino.

San

Marino was not immune from its own domestic

crisis. By the turn of the 20th Century the citizenry had become restive

under the Grand and General Council which had become increasingly

oligarchic. In a bold and unusual move

in 1906 the Sammarinese Socialist Party

agitated for and achieved a call to meeting of the ancient Arengo, where

the heads of families, under some public duress, voted to authorize universal manhood suffrage for the

first time in elections to the General Council.

The Socialists took advantage of the change to assume leadership of a majority coalition in the Council. The oligarchs formed a counter-party and bided their time for a chance to resume power.

The

eruption of World War I interrupted

the internal political struggles and put independence once again at risk. Italy initially entered the war on the side

of Austria-Hungary, honoring old

treaty obligations. Then in May of 1915,

Italy changed sides, declaring war on its former ally in hopes gaining

territory along the frontier between the countries. San Marino, however,

declared its neutrality, which was

taken as hostile by Italy which

feared that the small state could become a nest of Austrian spies and agents and that the country’s powerful new radio transmitter atop Monte Titano could be used by the enemy.

Italy

tried to force the occupation of San Marino by units of the Carabinieri paramilitary police which

the Republic refused and resisted. In

retaliation Italy cut San Marino’s telephone

lines and established a partial blockade. The Italians did not, however, invade the

country.

Still

within San Marino there was some popular support for the Italians. Small numbers of Sammarinese formed a volunteer unit to fight with the

Italians. Another volunteer group set up

a Red Cross field hospital. This was regarded as hostile by the

Austrians who broke diplomatic relations

and threatened the country should the front

move its way.

The

Italians fared poorly in a brutal campaign that turned into retreat and then

stalemate. The Sammarinese once again

offered shelter to refugees.

In

the aftermath of World War I the old oligarchic faction reorganized under Giuliano Gozi, one of the volunteers

with the Italian army and then serving as both Foreign Minister—effectively the leader of the Cabinet—and Interior

Minister which put him in control of the Army and police forces. Gozi founded the Sammarinese Fascist Party, modeled on the Italian Party, in 1922

and used street thugs to intimidate

the Socialists and syndicalists—unionists. In 1923 Gozi was elected the first

Fascist Captain Regent. After 1926 all

other parties were banned and until the end of World War II both Captains Regents were Fascist in contradiction to

the ancient Constitution. Although San Marino had become a single party state, Fascist power was not absolute, however, and independents continued to hold a

majority in the Grand and General Council until 1932. After that a split in Fascist ranks weakened

the Party.

Despite cordial relations with Mussolini and the Italian

Fascists, San Marino once again declared its traditional neutrality with

the outbreak of a general European War in 1939.

It had already not followed the Italian Party’s lead in adopting Anti-Jewish legislation in 1938. It had a small, but long-standing

Jewish population, and after persecution began in Italy some Jews found refuge

in San Marino. During the war anti-fascist Italian Partisans also

occasionally found secret refuge there, although the local Fascists expelled

those who were discovered.

In 1940 the New York Times erroneously reported

that San Marino had declared war on Britain. The Sammarinese government scrambled to wire London denying entering the war.

With the fall of Mussolini in Italy in July of 1943 and the subsequent

official separate peace with the Allies,

the Sammarinese Fascist Party lost power, although they were briefly

restored in 1944. The Fascists

reiterated neutrality in April of 1944 but the British bombed the country on

June 26 believing it was a repository for military supplies for the Germans. The government denied allowing munitions of any nation to be stored on

its territory.

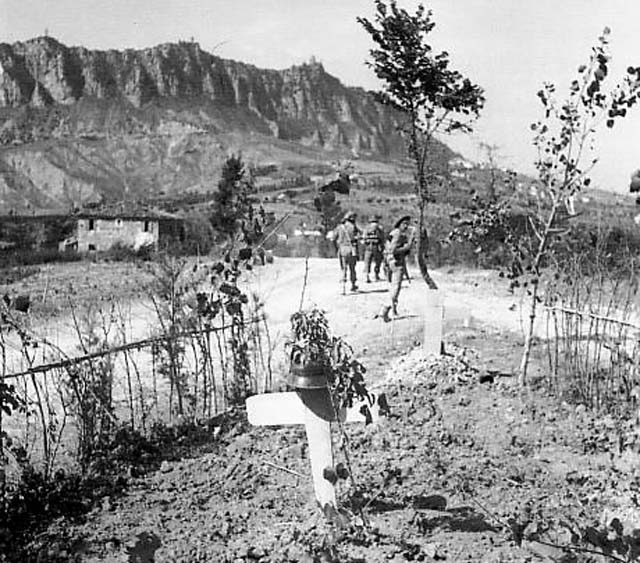

Indian troops passing the grave of a German soldier. After they cleared out the Nazis in the Battle of San Marino in 1944 the British withdrew their troops from the tiny nation.

In early September the Germans forcibly occupied

the country, the first and only time the country was overrun by a hostile

power. The Germans were already in

general retreat in Italy. On September

17 the 4th Indian Infantry Division

attacked the Nazis and ousted them in the brief Battle of San Marino. After

driving the Germans out the Indians quickly withdrew and left the country in

the control of its own armed forces.

The German occupation effectively finished the

Fascists as a political force in San Marino.

Multi-party parliamentary government was restored and in 1945 a

coalition led by the Communists

achieved a majority and ruled until 1957.

It was the first time anywhere in the world that Communists formed an

elected government.

The Grand and General Council was for years split

between multiple parties, some of them quite small, a mirror of the situation

in Italy. In 2008 a new election law put

restrictions on small parties forcing most of them out of existence or to join

coalitions. There were two main opposing

coalitions, the Pact for San Marino, led

by the Christian Democratic Party, and the United Left, led by the

Party of Socialists and Democrats, a merger of the Socialist Party and the

former communist Party of Democrats. Today the center-right party coalition is

the Republica Futura which was

formed by fusion of the Popular Alliance

(AP) and the Union for the Republic

(UPR). The other side has reformed as

the Democratic Socialist Left. The frequent turn-over of Captains

Regents has resulted in San Marino having more recognized female heads of state than any other nation in the world—15, including three who served twice.

Today San Marino is the smallest member of the Council of Europe but it is not a member

of the European Economic Union or

the European Parliament. None the less, it is by agreement allowed

to use the Euro as currency and as is customary has its own national images printed on the obverse side of notes, most of which

are snapped up by collectors.

With an economy relying heavily on finance, technical services,

and tourism, the approximately

35,000 residents enjoy the highest per

capita income in Europe and are the only country on the

continent with more automobiles than

people. Its citizens are also among the most highly educated in Europe. Unlike many small nations with substantial

finance industries, San Marino does not rely on being a tax shelter. There is a corporate profits tax rate of 19

percent. Capital gains are subject

to a five percent tax, and interest

is subject to a 13 percent withholding

tax. Foreigners use San Marino

banks for their renowned stability

and the high level of technical and personal services.

By agreement Italy is responsible for the general defense of San Marino, but the

country maintains a fairly sizable military

establishment for its size. This

includes colorful units with largely ceremonial duties including the Crossbow Corps, Guard of the Rock (also

a combat unit and border patrol), and Guard

of the Council Great and General (which protects the government). In addition every family with more than adult

two males is required to provide a member of the Company of Uniformed Militia. Participation

is so popular that it is over subscribed.

No comments:

Post a Comment