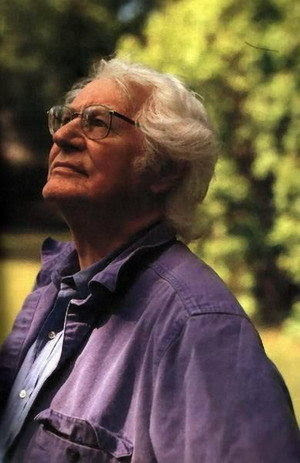

Robert

Bly, the

iconic and wayward Minnesota poet best known as the founder

of the sometimes controversial spiritual mythopoetic men’s movement

which tried to re-connect masculinity with nature and re-balance

the male role the sacred feminine, died Sunday in Minneapolis,

Minnesota at the age of 94. He

had been suffering from Alzheimer’s disease since at least 2012.

Bly,

through his publications, seminars, and tribal gatherings nurtured

new generations of ecopoets.

The men’s movement he spurred with the publication of his book

Iron John: A Book About Men in 1990 exploded in popularity

and participation around the turn of the 21st Century. Considered by some as an answer to second

wave feminism and women’s’ liberation, he intended it as a complimentary

movement, a point lost on many of its most enthusiastic participants. It was also widely mocked for promoting

arcane drum circles of naked men in the woods.

In

the interest of full disclosure, I was one of the mockers when a

Bly inspired men’s group briefly flourished at the old Congregational

Unitarian Church in Woodstock about 2000.

Garrison

Keillor eulogized his

fellow Minnesotan yesterday on his Writer’s Almanac podcast:

He was born in

Madison, Minnesota on December 23, 1926. A high school teacher taught him to

appreciate poetry, but he didn’t start writing seriously until he joined the

Navy after high school. There he befriended a man named Eisy Eisenstein — the

first person he had ever met who wrote poems. After the Navy, he spent a year

at St. Olaf College on the GI Bill. He said: “A woman my age wrote poetry; I

fell in love with her, and I wrote a poem to her. I had the strangest

sensation. I felt something in the poem I hadn’t intended to put there. It was

as if ‘someone else was with me.’” He transferred to Harvard and applied to

work as an editor for the literary magazine, the Harvard Advocate. When the

staff interviewed him for a position, he responded with a long, detailed

critique of American poetry since 1910. The staff seemed unimpressed, but they

accepted him anyway. One day a new student board member turned up, a poet a

year younger than Bly named Donald Hall. They became best friends.

After Bly left

Harvard, he decided that he didn’t want to teach at a university — he was

inspired by his idol, William Carlos Williams, and also by Wallace Stevens,

neither of whom was a career professor. So, he returned home to his family’s

farm in western Minnesota and began to write. Since he was so far away from a

literary community, he wrote frequent long letters to his friends and peers:

Donald Hall, Tomas Tranströmer, Galway Kinnell, Louis Simpson, and others. Bly

and Hall exchanged letters twice a week for decades, with a rule that they had

to respond to each other within 48 hours.

Bly’s

early collection of poems, Silence in the Snowy Fields,

was published in 1962. Its plain, imagistic style had considerable influence

on American verse of the next two decades. The following year, he published A

Wrong Turning in American Poetry, an essay in which he argued

that the vast majority of American poetry from 1917 to 1963 was lacking

in soul and “inwardness” because of a focus on impersonality

and an objectifying intellectual view of the world. Bly

believed this approach was instigated by the Modernists and

formed the aesthetic of most post-World War II American poetry.

He criticized the influence of Modernists such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra

Pound, Marianne Moore, and former idol William Carlos Williams—a virtual

who’s who of the most revered American poets. He argued that American poetry

needed to model itself on the more inward-looking work of European

and South American poets like Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo,

Antonio Machado, and Rainer Maria Rilke. A Selected Poems

translation of Rilke from the German, with Commentary by

Bly, was published in 1981. Times Alone, Selected Poems of Machado,

with facing pages of Spanish/English translation, was published

in 1983.

In

1966, Bly co-founded American Writers Against the Vietnam War and was

among the leaders of the opposition to that war among writers. In 1968,

he signed the Writers and Editors War Tax Protest pledge, vowing to refuse

tax payments in protest against the war.

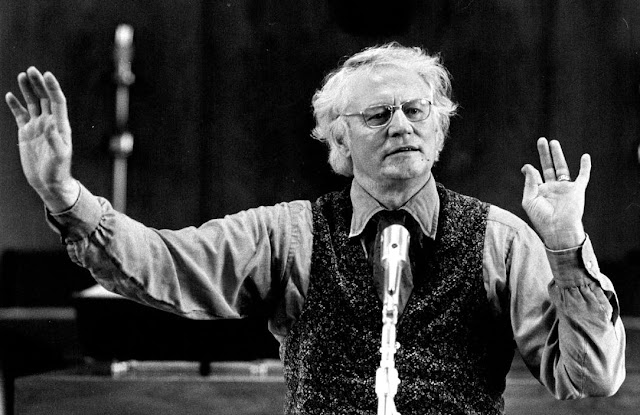

In his speech accepting the 1968 National Book Award

for The Light Around the Body, he announced that he would be contributing

the $1000 prize to draft resistance organizations.

Bly’s

development of his men’s movement had its roots in his close association

with the Great Mother Conference in 1975. The nine-day event featured poetry, music,

and dance to examine human consciousness. The event became annual, and Bly

attended every year through 2007. In the

early years, its major theme was the Goddess or Great Mother,

as she has been known throughout human history. Much of his collection Sleepers

Joining Hands from 1973 was concerned with this theme. In the context

of the Vietnam War, he saw a focus on the divine feminine was

seen as urgent and necessary. Since that time, the Conference has

expanded its topics to consider a wide variety of poetic, mythological,

and fairy tale traditions. In the 1980s and ‘90s Bly led the discussion

in the conference community about the changes which contemporary

men were going through resulting in The New Father, over the objection

of some feminists, was added to the Conference title.

Bly

published more than 40 collections of poetry, edited many others, and published

translations of poetry and prose from such languages as Swedish, Norwegian,

German, Spanish, Persian, and Urdu. His book The Night

Abraham Called to the Stars was nominated for a Minnesota

Book Award. He also edited the prestigious Best American Poetry in 1999

for Scribner’s.

In

2006 the University of Minnesota purchased Bly’s archive,

which contained more than 80,000 pages of handwritten manuscripts; a journal

spanning nearly 50 years; notebooks of his morning poems; drafts

of translations; hundreds of audio and videotapes, and correspondence

with many writers such as James Wright, Donald Hall, and James

Dickey. The archive is housed at Elmer L. Andersen Library on campus.

In

February 2008, Bly was named Minnesota’s first poet laureate. In that year he also contributed a poem and

an Afterword to From the Other World: Poems in Memory of James

Wright. In February 2013, he was awarded the Robert Frost Medal,

a lifetime achievement recognition of the Poetry Society of America.

In a

separate post Keillor shared one of the Morning Poems Bly faithfully recorded

in his notebooks each morning, one of his regular spiritual practices.

Every day around dawn Robert Bly

Writes a poem, that is no lie,

And the poem he composes

At the end of his nose is

Looking him straight in the eye.

And with great clarity

Addresses posterity

Though he is not intending to die.

—Robert Bly

Despite,

or perhaps because of his mysticism, Bly remained engaged as a social

critic and particularly as a pacifist.

Call and Answer

Tell me why it is we don’t lift our

voices these days

And cry over what is happening.

Have you noticed

The plans are made for Iraq and the

ice cap is melting?

I say to myself: “Go on, cry.

What’s the sense

Of being an adult and having no

voice? Cry out!

See who will answer! This is Call

and Answer!”

We will have to call especially

loud to reach

Our angels, who are hard of

hearing; they are hiding

In the jugs of silence filled

during our wars.

Have we agreed to so many wars that

we can’t

Escape from silence? If we don’t

lift our voices, we allow

Others (who are ourselves) to rob

the house.

How come we’ve listened to the

great criers—Neruda,

Akhmatova, Thoreau, Frederick

Douglass—and now

We’re silent as sparrows in the

little bushes?

Some masters say our life lasts

only seven days.

Where are we in the week? Is it

Thursday yet?

Hurry, cry now! Soon Sunday night

will come,

—Robert Bly

Other

times that famous mysticism shone clearly.

Living at the End

of Time

There is so much sweetness in children’s voices,

And so much discontent at the end of day,

And so much satisfaction when a train goes by.

I don’t know why the rooster keeps crying,

Nor why elephants keep raising their trunks,

Nor why Hawthorne kept hearing trains at night.

A handsome child is a gift from God,

And a friend is a vein in the back of the hand,

And a wound is an inheritance from the wind.

Some say we are living at the end of time,

But I believe a thousand pagan ministers

Will arrive tomorrow to baptize the wind.

There’s nothing we need to do about John. The Baptist

Has been laying his hands on earth for so long

That the well water is sweet for a hundred miles.

It’s all right if we don’t know what the rooster

Is saying in the middle of the night, nor why we feel

So much satisfaction when a train goes by.

—Robert Bly

No comments:

Post a Comment