Tom Horn is

a kind of litmus test of conflicting,

class driven, views of Western

history. Depending on who you ask the soft spoken man who

was hung for shooting a 14 year old boy in the back and killing him was a misunderstood hero, the beau

ideal of a cowboy, lawman, and range detective

or a ruthless, pitiless gun for hire.

These two visions are represented

in American culture by two iconic

but contrasting western

stories. Owen Wister’s The

Virginian had as its hero

the noble foreman of a great ranch who led a fight against rustlers and thieves. Years later in the classic film Shane, Alan Ladd would play a drifter with a past who would stand up to a cattle baron on

behalf of sod buster farmers.

In 1901 the days of the wild

and woolly frontier were fading

fast, even in Wyoming. After gaining statehood in 1890,

the bloody Johnson County War between the ranching barons of the Wyoming

Stock Growers Association and their small,

hired army of gunslingers

and plug-uglies and the small

ranchers and homesteaders suspected of throwing the occasional long lasso over the necks of cattle had officially ended in 1892. That’s

when a local sheriff with the assistance

of the Cavalry rounded up the gang

of the gunmen besieging an

isolated ranch. They were hauled

to Cheyenne for trial. But oddly, while out on bail, all slipped

away.

The plutocrats of

the Stock Growers Association and the state

government in the hands of their handpicked

officers laid low for a

while in their mansions and in the impressive headquarters that dominated the city’s downtown.

They helped establish Cheyenne Frontier Days, the oldest municipal rodeo, to celebrate the fading glory

of the unchallenged Open Range and import tourists. By the turn of the

century some of them were toddling around town in newfangled and expensive

automobiles. But despite the

appearance of modernity, they had re-launched their old campaign

against small holders, on a scaled back level amounting to a low grade guerilla war.

Enter Tom Horn.

Horn was born on a 600 acre farm on the South Wyaconda

River in northeast Missouri’s

Scotland County on November 21, 1860. He was about in the middle of a pack of twelve

children. Not much is known about his childhood other than it was probably pretty typical as any in its time

and place.

By age

16, like many younger sons with a taste for adventure and no hope of inheriting the family farm, Tom headed west. He knocked around the Southwest

picking up the skills of a cowboy. In 1883 he was enlisted as a civilian Cavalry scout under Albert Sieber for General

George Cook’s campaign against Chiricahua

Apaches under Geronimo. The German born Sieber took the young man under his wing and mentored

him, even taught him to speak German, as well a much tracking

and trailing lore.

The

Scouts accompanied Cook when he illegally

crossed into Mexico seeking the elusive Geronimo in the Santa

Madre Mountains. In 1886, after Geronimo and a handful of followers escaped Cook’s custody, Horn was assigned to a small contingent

commanded by Captain Henry Lawton of B Troop, 4th Cavalry

and First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood to once again go

into Mexico. The Mexican’s hated Geronimo but were also sensitive about their sovereignty.

Horn was wounded when local militia attacked his camp. Later he killed his first known man,

and the only one in a stand-up idealized

western gun duel—a dust up with

a Mexican officer at a cantina.

When

Lt. Gatewood finally found Geronimo’s camp with Horn’s help, Seiber was

elsewhere. It was Horn who translated

at the delicate negotiations that

resulted in the old chief’s final

surrender.

At loose ends after the essential end of the Indians wars in the Southwest, Horn drifted back into cowboying then staked a mining

claim. It did not take long however, for him to enter the Arizona

Pleasant Valley War as a hired gun.

But it is not clear to which side he

sold his services. Also known

as the Tonto Basin Feud it was a long

running conflict between two large ranching families, the half-Indian

Tewksburys and the Grahams over land and water rights as well as mutual rustling. It had been a deadly affair since 1882 and

intensified in ’86 when the Tewksbury’s introduced

sheep to the range.

In his

autobiography Horn said he joined in the pursuit of rustlers,

which could refer to either party.

But given his later proclivity for

cattle ranchers and enmity toward Indians it is likely that he accepted the pay of the

Grahams. Both families and their employees were victims of several unsolved slayings, some of them perhaps

by Horn acting as a “regulator”.

Taken together, both families were nearly

wiped out and the conflict

has been called the deadliest feud in

American history, far outstripping the body

count of the Hatfields and McCoys or the earlier Arizona Lincoln

County War made famous by Billy the Kid. Killing continued

into the early 1892 when the last

Tewksbury killed the last Graham.

Sporadically

during and after the Pleasant Valley war, Horn also served as a deputy sheriff prized for his unmatched

skill as a tracker. He served under three

of the most famous Southwest lawmen,

William “Buckey” O’Neill, later a Captain

in the Rough Riders killed in Cuba; long haired Commodore

Perry Owens of Apache County; and former Confederate Glenn

Reynolds. Each of them, at one time or another, intervened in

the Feud and Horn’s status as deputy may likely have been paid for by one or the other side when

posse went after the other.

Horn’s

exploits as a gun for hire and

erstwhile lawmen became celebrated

enough to come to the attention of the Pinkerton Detective Agency

which hired him in 1890 as one of its operatives out of the Denver office. He specialized in

tracking down those that stole

effectively from the rich—rustlers, train, and bank robbers.

In his most famous case, he tracked Thomas Eskridge “Peg-Leg” Watson

and Burt “Red” Curtis who were suspected

of a robbery of the Denver

& Rio Grande Railroad in August of 1890 all the way from Colorado to a hideout in Oklahoma Territory.

His orders were to bring the men in. He

and his partner took the men “with no

trouble and without firing a shot.”

Horn

by this time considered himself a

professional. He held no

personal animus to any of the men he relentlessly

tracked down. As a professional he did what he was ordered.

If the Agency wanted the publicity of

nabbing two semi-famous outlaws and bringing them to justice, he was the man for the job. It the Agency

or its wealthy clients preferred that their problems be eliminated, Horn had

no trouble with that either. Some of the men he hunted ended up dead, generally shot from ambush in ways in

which the killing could not be linked to the shooter, the company, or the client.

Horn considered himself honorable and consoled any qualms of conscience by telling himself he was

working for if not law, then at least some

sort of avenging justice.

By

1894, however, too many people were

ending up dead in Horn’s vicinity.

He resigned from the Pinkertons

under pressure. It was not

that the agency was displeased with the results of his work. When

one of the best known of Pinkerton’s

western operatives, Charlie Siringo who had worked closely with Horn published a memoir Two Evils: Anarchism and Pinkertonism he claimed that, referring to one case that

“William Pinkerton told me that Tom Horn was guilty of the crime,

but that his people could not allow him to go to prison

while in their employ.”

Although

no longer an employee, Horn would continue to sometimes work with the agency and was sometimes contracted by them to work on specific

cases in his new role as an independent

Range Detective for hire. One of his most reliable

clients was the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, the biggest employer of hired

gunmen in the West. They put him to work on cases in the Johnson

County War.

He was

thought by many to be among the

gunmen who killed Nate Champion the leading

spokesman of the small ranchers

that the Association accused of rustling. Champion was the first victim of the all-out war. He was besieged in his cabin at the KC

Ranch where he held off a posse of 200 sheriff’s deputies and

Association gunmen for hours, keeping while keeping a journal of the battle. He was cut down by fire from five men,

allegedly including Horn, when he ran from the cabin on April 9, 1892.

It was

sheer luck that Horn was not among

the Association gunmen arrested later that year—he was off working, as

he generally preferred, alone and independently at the time.

In

1895, now an independent agent for the Association, he was accused of killing William

Lewis near Iron Mountain, Wyoming and six week later another

alleged rustler, Fred Powell. He avoided being charged in both

cases due to the powerful political

influence of the Association. The following year a small rancher

named Cambell, who had just sold some cattle and was caring a large amount of cash, vanished after last being seen in the company of Horn. There were other murders or

disappearances on the range in those years. Horn may or may not have been involved—he was not the only gunman on the loose, just the most notorious.

Still,

occasionally Pinkerton would call on Horn to investigate real criminals. He was contracted to investigate

the Wilcox train robbery, committed by members of Butch Cassidy’s Hole in the Wall Gang. He

identified two members of the gang, George Curry and Kid Curry as

the likely killers of Sheriff Josiah Hazen who had been shot in pursuit of the gang. He passed the information on to

Pinkerton Siringo.

Patriotically, Horn, like many

westerners, volunteered in the Army for the Spanish American War. Before he could

ship out to Cuba, however, he was struck

down by malaria, which was rampant

among the troops, in Tampa. He never got to see action and it took some

time for him to recover his health.

Back

in Wyoming by 1899, Horn was working for the Swan Land and Cattle Company

and was known to have killed two rustlers, Matt Rash and Isom Dart.

A year later, working in Colorado, he was suspected

in the ambush killing of two other suspected cattle thieves.

In

1901 he was employed by cattle baron John C. Coble. He was

working around an old stomping ground, Iron

Mountain, when his attention was

drawn to small rancher named Kels Nickell who was running

sheep on the range.

On

July 18, 1901 Nickell’s 14 year old son Willie was shot from ambush

twice while opening a

gate at his father’s ranch.

Two bullets tore completely through his body,

one piercing his back and another entering his shoulder and traversing his body

sideways and down, indicating that he was either twisting from the impact of the first round, or as some later investigators of the shooting

believe, hit by a round from a second shooter.

A few

days later Willie’s father was also shot

and wounded.

Horn

was known to be in the area and interested in the Nickells. He left immediately after the

shooting. A year later, drunk and supposedly remorseful for killing the boy instead of his father,

Horn allegedly confessed to an old acquaintance Joe Lefors, a deputy U.S. Marshall. Although

many would later question the confession, he was charged with the murder.

When

arrested he had in his possession a Winchester Model 73 lever action rifle, too small a caliber to have been

used in the Nickell murder. But he had in his pocket two rounds for larger caliber rifles, either of which might have been capable of producing Willie’s wounds. With no eye witnesses, this circumstantial

evidence, the questionable and recanted confession, and the knowledge

that his employer had targeted the Nickell ranch, was all prosecutor Walter Stoll had to go on.

It turned out to be enough. The public was getting sick of continued violence

on the range, and all of the Stock Growers Association political clout could

not, for once, get around it.

At the

trial the defense tried to show that

neighboring rancher Jim Miller

with whom the elder Nickell had clashed

over his sheep had a motive to kill. The testimony came from

an attractive school teacher, Glendolene

M. Kimmell who boarded at the Miller ranch and who was romantically

linked to Horn. But that was not

necessarily exculpatory for

Horn, who would have used Miller as an asset in his investigation of Nickell, and who might have even been encouraged by him to do the shooting.

Whatever

the case, the jury returned a verdict

of guilty. Horn’s appeal to the Wyoming Supreme Court failed. Tom Horn was going to hang.

All

the time Horn was sitting in his jail cell he serenely passed his time braiding a

two-color horse hair riata in the old Southwest style. He was visited

frequently by Miss Kimmell who gathered

from their conversations and Horn’s notes the material for the publication of Horn’s Autobiography

in Denver in 1904. Horn also visited and modestly conversed with reporters and even

visiting celebrities including Heavyweight

Boxing Champion Gentleman Jim Corbet. His quiet, pleasant demeanor impressed many visitors. He just didn’t seem like a hardened killer.

None-the-less,

Horn was hung in Cheyenne on November 20, 1903. He was just past his 43rd birthday.

Since

then, Horn has lapsed into folk

hero/villain status. He was the subject

of several western novels and stories

either under his own name or

inspiring thinly veiled characters.

At least one totally fiction western

movie, Fort Utah staring John

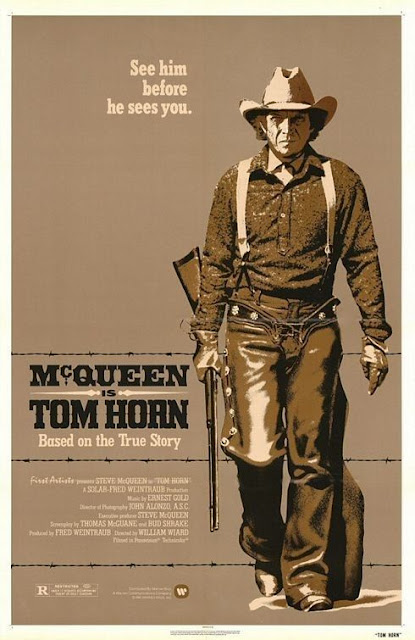

Ireland in 1967 cast him as a hero. Best known film version was Tom Horn

released in 1980 with Steve McQueen sympathetically

portraying him as a man lost out of his time and confused by the emerging modern world. David Carradine played him in

a made for TV movie, Mr. Horn a year earlier. And

the History Channel produced a documentary

claiming to clear Horn of this particular murder

or cast doubt on

his guilt.

Western historians are divided on the case. A good many

believe that despite the scant evidence, Horn was probably guilty. Others believe that he accidently killed the boy intending to kill the father and many of these would have excused the execution of the older man as rough range justice. Others

believe he may have only been peripherally involved by perhaps fingering the Nickells for another shooter or abetting the Miller family.

Some think he may have been one of two shooters. Others buy the two

shooter theory but believe it was the work of the Millers. And decedents of the old cattle barons and

their defenders still maintain that

Horn was entirely innocent and the victim of persecution by small

rancher/rustlers and a lynch mob of

public opinion.

Take your pick.

As for

me, however sympathetic and compelling he or Steve McQueen might have been, Tom Horn was a killer who was bound someday for the noose—even if he didn’t shoot Willie

Nickell.

Rarely have I read anything to do with the West unless it involved labor but enjoyed this piece. To bad all these hired guns, plus uglies, and mostly the plutocrats who ran their cattle kingdoms like kingdoms didn't smoke themselves to death like the Marlboro man. LOL!

ReplyDeleteI grew up in Cheyenne in the early 50's and 60's and heard many stories about Tom Horn. In the 7th grade, our Wyoming History teacher told us many stories of Tom Horn and of his hanging in Cheyenne. She remembered it well, because as a young girl she was at the hanging and saw them hang Tom Horn. Trin Rios

ReplyDelete