Tonight is Bonfire Night across the Puddle,

traditionally a rowdy celebration of

the day Guy Fawkes got caught trying to blow up

Parliament on November 5, 1605. Originally celebrated on the first anniversary as an official Thanksgiving Day for delivering the King and Parliament from

the Catholic plotters, it became an annual official holiday until that status

was finally dropped in 1859 because

of the virulent anti-Catholic tone

of the celebration.

Traditionally effigies of Fawkes

were burned on bonfires.

Later fireworks also became popular

along with considerable public revelry and occasional outbreaks of vandalism

aimed at Catholic churches and schools.

In recent years the celebration has tamed and faded. Municipalities clamped down on celebrations limiting them to officially organized bonfires.

Previously children would haul Fawkes effigies around town

for days collecting wood for private bonfires or money to buy it. Fires were

often built on city streets and on vacant lots. Many locations also moved commemorations from November 5 to

a weekend to keep interference of commerce to a minimum. But the two biggest blows were a national ban on the sale and possession of

fireworks by individuals and the encroachment of the Americanized commercial Halloween

just a few nights earlier. None-the-less, across England, in Ulster, and to a lesser extent in Scotland and Wales, there will still be celebrations.

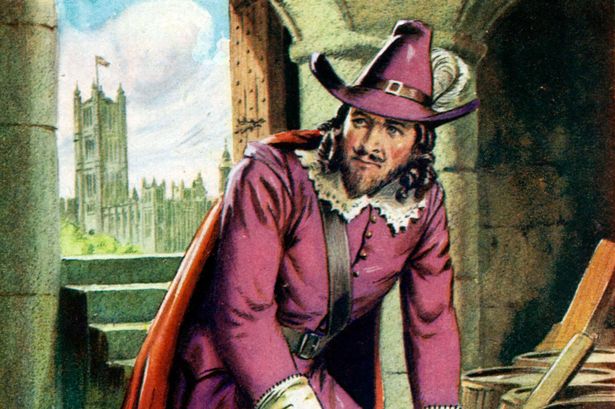

Depending how you look at him, the Guy Fawkes was either a religious fanatic who ran away to become a combatant

in foreign wars and returned home to become a terrorist—sort of like a 17th Century Catholic al-Qaida—or a swashbuckling resistance fighter depending on your outlook.

Fawkes was born

in 1570 to a respectable Protestant

family in York. Members of this mother’s family were Recusants—those who refused to worship in the Established Church and were suspected of being Catholic. His

father died when the boy was eight and several years later his mother remarried a Catholic.

He attended St

Peter’s School in York, which was known to have Catholic sympathies and several of his

classmates were subsequently prosecuted as Recusants and some

became Priests. Exactly when Fawkes personally converted to Catholicism is a matter of some debate, but he was surely practicing in secret

by the time he took up the career of a soldier and

entered the service of the Catholic noble

the Viscount Montagu.

In 1591 Fawkes sold his estate and traveled

to the Netherlands to enter the service of Spain against the

Protestant Dutch Republic. He also served Spain in its war with France

and so distinguished himself at

the siege of Calais in 1596 that he

was promoted to Captain in 1603. The same year he traveled to Spain and petitioned

the court of Phillip III

for support in raising an army to overthrow James I and restore the English and Scottish monarchies (united under James) to Catholic hands. But Phillip was then pursuing a peace policy with England and, although sympathetic, refused to help.

Sometime in

1604 Fawkes, now using the Italian

form of his name, Guido, returned to

England and soon connected with Robert

Catesby who had already begun to assemble

a small cadre of Catholics to

undertake the assassination of King

James and place his nine-year-old daughter Princes

Elizabeth on the throne as a Catholic ruler. Fawkes first met the rest of

his fellow conspirators on May 20, 1604 at the Duck and Drake, in the fashionable

Strand district of London.

The other men were impressed

with Fawkes both personally and for

his confidence and military skill. And having been out of the country for years, he would

not be recognized by local

authorities. Fawkes confirmed what Gatesby already knew, that the

plotters would not receive help from Spain. They determined to press on.

Fawkes secured rooms adjacent to Parliament. The plotters may—or may

not—have begun an attempt to dig a

tunnel from the house cellar.

If so, they abandoned the project when they discovered that the land lady had an undercroft—a

cellar storage room—directly under the House of Lords. Hardly believing their good fortune, they leased the space arousing no suspicion, and

began smuggling in barrels of gunpowder, which they hid under firewood and coal.

Eventually, more than thirty barrels, more

than enough to blow the building sky high, were hidden there.

Although the

gun powder was in place by August 1602, the plotters had to wait until the opening of Parliament

when James and the Court would be in attendance.

This was delayed several times because the plague

was making one of its periodic re-visits

to London. In the meantime, Fawkes was to guard the stash and be prepared to light the fuse to ignite the explosion when the

time was right. When the bombs went off and the King was dead, other

plotters would raise a

rebellion in the Midlands to put

Elizabeth on the throne.

But more than twenty people were actively

involved in the plot—far too many

to keep such a secret for

long. At least one of them was worried

about Catholic nobles who might be killed and sent an anonymous warning to Lord

Monteagle to stay away from the upcoming ceremonies because “... they shall

receyve a terrible blowe this parleament.” Monteagle showed the letter to the King who ordered that all of the cellars in and

around Parliament be searched.

On November 5, the King’s men

discovered Fawkes coming out of the undercroft. Upon arresting him, they uncovered the barrels of gunpowder

hidden in the room.

Under questioning in King James’s presence,

Fawkes used the alias under which he

had secured the rooms, John Johnson, but admitted to being a Catholic and

planning to blow up Parliament. He would not, however, reveal the names of any associates. The king ordered the

prisoner tortured.

He was taken to

the Tower of London and subjected to

several sessions of torture of increasing severity. He held mum through the first, but slowly began to crack. On November 7, he admitted his identity. On

November 8 and 9 he began to name names.

He signed a confession in a barely

legible scrawl, a testimony to the severity of his suffering.

It did not take

long to round up some of the other

conspirators. On January 27, 1606 Fawkes and seven others were placed on trial at Westminster Hall. The outcome

was never in doubt. All were convicted of High Treason and by

custom condemned to be drawn and quartered, a gruesome

punishment in which the prisoner’s genitals

were cut off and burnt before his eyes, bowels and heart removed,

before final decapitation. Then the dismembered body parts would be displayed to become the “prey for the

fowls of the air” and any remaining parts would be scattered across the

kingdom.

On January `31

Fawkes and three other were taken to a high

scaffold in front of Westminster Hall. The first three suffered as

planned while Fawkes was forced to

watch. Then he calmly mounted the scaffold and made a brief statement. Then, he managed

to break free and dive from the platform, breaking his neck and dying almost immediately. He escaped the pain of being drawn and

quartered, but not to be denied, his executioners finished the job on his

corpse.

The following

November 5, the King proclaimed the Thanksgiving

Act establishing the custom of Bon

Fire Night.

The custom accompanied

the Puritans to New England. By the early 1700’s it was known as Pope’s Day in Boston. Despite the fact the few in the city had ever even seen a Catholic, it was a day of riotous disrespect. Parades were organized in which not

only effigies Guy Fawkes, but the Pope himself

was carried to bonfires to be burned. These parades were organized by the apprentices and laborers

of the town. Eventually there were rival

parades on the North and South sides, often accompanied by semi-ritualized

gang fights between the groups. Yet out of this unlikely start patriots led by Samuel

Adams began to organize the two

groups into sections of his Sons of Liberty, channeling rowdyism into a new

and unexpected form.

Despite this, George Washington had

to ban Pope’s Day observances in the

Continental Army out of respect for Catholic troops from Maryland and because the celebration inferred an allegiance to the Crown.

Guy Fawkes masks have become a staple of street demonstrations around the world.

More recently

the move V for Vendetta based on a D.C.

Comics limited series and starring Natalie Portman, Hugo

Weaving, Stephen Rea, and John Hurt released

in 2005 became a cult hit. In it a band of rebels against a future

dystopian Fascist British regime are led by a charismatic and mysterious figure

known only a V who always wears a stylized Guy Fawkes mask. Those

masks spread like wildfire across Europe along with a wave of massive anti-austerity

street demonstrations and strikes. On the other side of the Atlantic they were popular during Occupy Movement marches and demonstration. The masks were widely adopted by anarchist militants and among the Anti-fa.

They turned up on mostly white

supporters at Black Lives Matter

actions where some of the masked figures broke from peaceful demonstrations

to smash windows,

over-turn cars, and battle police. The mask was also used for video pronouncements by Anonymous.

There is more

than a little irony in that the image of Guy Fawkes—the Catholic

plotter and Royalist—became a revolutionary street radical icon.

Certainly nothing would have surprised him more.

No comments:

Post a Comment