There were a lot of threads to

the youth culture being woven on the

streets of San Francisco—the older,

now established Beats finding new

followers for their expressions of alienation,

spiritual quest, and rebellion through art and poetry; a

ramped-up music scene revolving around a bunch of local bands inventing a new American

rock & roll sound; a quasi-anarchic radicalism spreading from the Anti-Vietnam

War movement and near-by college

campuses; the introduction of cheap, free, and then legal LSD and other hallucinogens

plus wide spread availability of Mexican

marijuana; the sexual revolution made possible by the pill; a flood of teenage

runaways and throwaways living

on the streets often engaging in virtual or real prostitution to survive; the large Hells Angels motor cycle club with their sometimes violent

culture; and a community of spiritual

seekers drawn to a range of mostly Eastern

Religions and cults.

All these threads seemed to come

together on January 29, 1967 for an event at the Avalon Ballroom called The

Mantra-Rock Dance. In retrospect it

is remembered as “the ultimate high” and as “the major spiritual event of the

San Francisco hippie era.” It was one

intense, cathartic night that participants thought opened a door

to a new future.

It started simply enough as just

another local benefit. All sorts of local San Francisco organizations and causes raised money and awareness with benefit concerts held at

various halls and venues, often ballrooms built to accommodate big bands. Local rock bands had been building followings

for years starting out at benefit shows.

Some had gone on to play at Bill

Graham’s Fillmore West for cash

money, had signed recording

contracts with major labels, and

were now national acts verging on super stardom. But these same big acts still lived in

the community and feeling connected to it. Even the biggest could be lured back

to a benefit show for a good cause in front of the fans that first boosted their careers.

So it was not without hope that Mukunda

Goswami, the former Michael

Grant and a Reed College graduate and jazz musician, decided

to have a concert to raise funds and publicize the new International Society for Krishna

Consciousness (ISKCON) West Coast Center and Temple in the heart of the Haight-Ashbury counter cultural

community.

A.

C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada,

usually referred to as simply Prabhupada, was a guru in a school of Vaishnavite

Hinduism which was one of the many strains of the traditional Indian religion and which took the Bhagavata

Purana as a central scripture and veneration of the god Krishna. He was pious, scholarly, and respected

by Western religious scholars

like Harvey Cox. He took it as his mission to bring

this traditional form of Hinduism to the West, founding ISKCON and his first

temple in New York City in 1965.

Prabhupada took advantage of rising

interest in Eastern religions fostered by both the Beat movement and liberal theologians. Interest in Hinduism in this country dates to

Ralph Waldo Emerson who studied

early translations of the Bhagavad Gita and adapted from it

many of the more mystical aspects of his Transcendentalism including his central idea of an Over soul.

In 1893 Swami Vivekananda created a sensation at the World Parliament of Religions held in

conjunction with the Columbian

Exposition in Chicago introducing

yoga to this country. His books became best sellers and the

practice of yoga spread across the country, especially in enclaves of the

highly educated. Yoga was widely

practiced by many of the Beats. But it

was viewed largely as a system of meditation

and most religious content from Hinduism and Buddhism had been stripped away.

By the 1960s many were ready to dig deeper into the roots of

meditative spiritual practices, the Hindu Vedas

or holy books and ritual practices.

Prabhupada’s New York temple catered

to that interest and was quickly successful.

Within two years the Swami had trained a core group of American-born

followers who he initiated as disciples. From this group he selected Mukunda Das to lead a team with half a

dozen others to establish the San Francisco temple in late 1966.

The group quickly attracted

attention and followers with their yellow

robes, shaved heads, street dancing and chanting, classes at the center, and free feeds for the community of brown rice and vegetables. To gain more followers and to raise

money to support the Temple Mukunda Das and his team quickly decided to tap

into the local tradition of rock benefits and to invite Prabhupada for his

first West Coast visit to participate in the event.

The idea was controversial

among the Swami’s New York followers.

The movement demanded abstention from drugs and alcohol and chastity or monogamous marriage among disciples. The San Francisco scene was already notorious

for its drug and free sex lifestyle.

Poet Allen Ginsberg, who had adopted Hare Krishna chanting in

his own spiritual practice and who was friendly with Prabhupada although not an

acolyte, convinced the guru that there was a spiritual hunger that he

could fill. Many, like Ginsberg himself,

would adopt at least some of the practices leaving the lifestyle restrictions

to full-fledged initiates. The Swami

agreed to attend on that basis and Ginsberg signed on to introduce him in

California and participate in public chanting.

With that in place Mukunda Das and

his team turned to lining up talent.

Through connections they quickly signed up two of the top San Francisco

bands—The Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company with

its lead singer Janis Joplin. Both bands agreed to perform for the Musician’s Union minimum of $250. Team member

Malati Dasi happened to hear Moby Grape, a relatively obscure

band just establishing themselves, and added them to the program—which would

catapult them to fame and a record deal.

The Fillmore was considered as a

venue, but Bill Graham, an old school Humanist

and secular Jew, was skeptical

of the new group. Instead,

organizers turned to the Avalon Ballroom managed by Family Dog impresario and

manager of Big Brother and the Holding Company Chet Helms. Helms was

supportive, if somewhat skeptical that the event would draw a crowd. He also agreed to provide the state of the

art light show for the event.

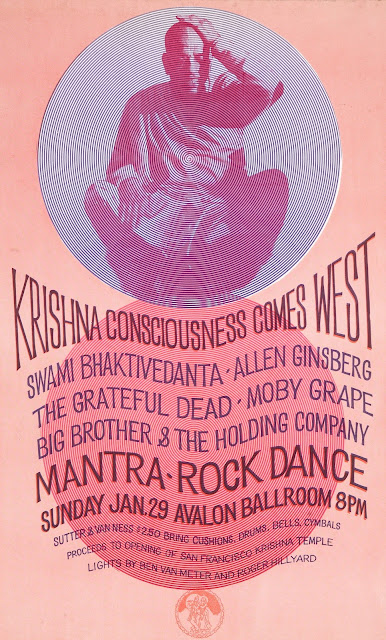

Artist Harvey Cohen, one of the first ISKCON followers, designed a in the

style of Stanly Mouse which featured

Prabhupada seemingly floating in a purple bubble and an invitation to “bring cushions, drums, bells, cymbals.” The posters were soon dotting the Haight and

were up at Bay Area college campuses.

More than ten days before the event on January

17 Prabhupada arrived at the San

Francisco Airport and was greeted by Ginsberg and more than fifty dancing

and chanting acolytes and hippies. The

Swami settled down to teaching at the temple and to giving occasional

interviews. His presence in the city

helped build excitement, especially after the San Francisco Chronicle published

a lengthy interview in which he was pointedly asked if all of those drug

crazed hippies were welcome to his

temple and he replied, “Hippies or anyone—I make no distinctions. Everyone is

welcome.”

The week before the show, Prabhupada

and the program were given an enthusiastic full page treatment in The

Oracle, the city’s underground

newspaper in an article headed The New Science.

Despite the growing hoopla both the organizers and Helms worried

about attendance on a Sunday night.

Even in any-thing-goes San Francisco Sunday was not a usual night

out.

But thousands showed up the evening

of the 29th ready to plunk down the $2.50 admission at the door. Despite warnings not to bring drugs,

marihuana hung heavily in the air. Acid guru Timothy Leary and his pal Owsley Stanley III, the manufacture

of famously high quality, powerful LSD were there and ss was Owsley’s custom he

brought hundreds of hits with him

and freely distributed them. Leary would

later be up on the stage with Ginsberg and the Swami.

3000 people filled the auditorium to

its capacity and hundreds waited outside.

Despite the crowding and the disappointment of those who

could not get in, the mood of the night was uniformly mellow. Prabhupada’s

biographer Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami

later described the scene:

Almost everyone who came wore bright or unusual costumes:

tribal robes, Mexican ponchos, Indian kurtas, “God’s-eyes,” feathers, and

beads. Some hippies brought their own flutes, lutes, gourds, drums, rattles,

horns, and guitars. The Hell’s Angels, dirty-haired, wearing jeans, boots, and

denim jackets and accompanied by their women, made their entrance, carrying

chains, smoking cigarettes, and displaying their regalia of German helmets,

emblazoned emblems, and so on—everything but their motorcycles, which they had

parked outside.

The crowd was fed Prasad—sanctified food—including orange slices as Helms’s light show was

projected on walls accompanied by pictures of Prabhupada and Hindu

deities. The program began with a parade

of disciples chanting Hare Krishna to an Indian raga. Moby Grape opened the

music program.

Around 10 pm Prabhupada entered the

auditorium from the rear. “He looked

like a Vedic sage, exalted and otherworldly. As he advanced towards the stage,

the crowd parted and made way for him, like the surfer riding a wave. He glided

onto the stage, sat down and began playing the kartals [ritual finger

cymbals],” his biographer recalled.

Ginsberg welcomed the Swami to the

stage in a rambling introduction that included a recommendation that

chanting was a good way to come down from LSD and “stabilize their

consciousness upon reentry.” Prabhupada

gave a short speech of welcome then Ginsberg led the crowed in the Hare Krishna

chant. After several minutes Prabhupada

arose and began dancing to the chant.

Others joined him on stage, including the members of all of the bands

many of whom played along with their instruments. The crowd joined in elated dancing and with

their own drums and bells.

Afterward Joplin and then the Dead

played on into the early morning hours.

Reactions to the event were ecstatic. $2,000 was raise, but more importantly so was

community consciousness. Attendance at

the temple swelled. Publicity from the

event helped propel Prabhupada into the national spotlight and he soon

embarked on long speaking tours and established many other temples.

Mukunda Das and other members of the

San Francisco team were sent to London to

establish a temple there and established a famous relationship with George Harrison who embraced Krishna

worship for the rest of his life and not only created his own devotional music—My

Sweet Lord—but produced an album of temple chanting that became a charted

hit in England and Europe.

By the early ‘70s the Hare Krishnas,

as they were popularly called, were a familiar sight on the streets of

many American cities, and especially at airports

where they engaged in chanting, ritual

begging, and the sale of flowers. There was also a backlash. ISKCON

was accused of operating as cult and

brainwashing its young acolytes to

keep them isolated at temples and rural communes or ashrams. This took the characteristics of a social panic as parents hired so-called

deprogrammers to essentially kidnap their children, hold them

against their will, and subject them to intensive “therapy” that was

itself a form a brainwashing all with the usual approval and acquiescence

of law enforcement.

Eventually religious scholars came

to the defense of the Hare Krishnas as a genuine religious movement with deep

ties to traditional Indian Hinduism and the organization lowered its public

profile somewhat.

The movement grew and spread,

despite the controversies. It was also

one of the few Western seeds of Eastern religions that retained,

and even grew significantly, a presence in its home country.

By the time that Prabhupada died in

1977 at the age of 81 he left behind 108 temples across the globe, plus

numerous farm communes, and study institutes. His publishing house, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust was and remains the world’s largest

publisher of ancient Hindu religious texts as well as modern commentaries

and has translated key texts into dozens of languages. Despite internal squabbles over leadership

succession that continue to this day, the movement has continued to grow

and counted over 400 temples worldwide in 2012 plus many home centers serving

small clusters in places remote from temples.

As for the dreams of the San

Francisco Hippies for a new beginning, well, that is another story.

Bravo! It was a time when western culture opened up in a big way to alternate cultural concepts. This is a nice rendition of how these threads all came together. I tried to blend Hare Krishna chants into my more eclectic spiritual quest, loved their food & free feeds, but eventually focused more on Buddhist traditions.

ReplyDelete